High-Performance Demonstration Home

A designer-turned-contractor showcases the benefits of a small, all-electric, healthful home.

As soon as my contractor’s license came in the mail, I broke ground on a superinsulated, all-electric, net-zero house—my personal first, and the first one in my village of Spring Green, Wis. (population 1641; climate zone 6).

I was confident in my plan, but nervous about my ability to vet and supervise the subcontractors I would need to execute it. I had spent the last 35 years behind a drafting board; my job-site experience was limited to quick dashes to meet with clients and check on progress. I had designed hundreds of custom homes, made valuable contacts with people in the renewable-energy and natural-building communities, and had expanded my knowledge of products, materials, and energy-smart construction details by reading articles in Fine Homebuilding, The Journal of Light Construction, and Green Building Advisor, and by attending the annual Midwest Renewable Energy Association Energy Fair. But I needed the right building team on board.

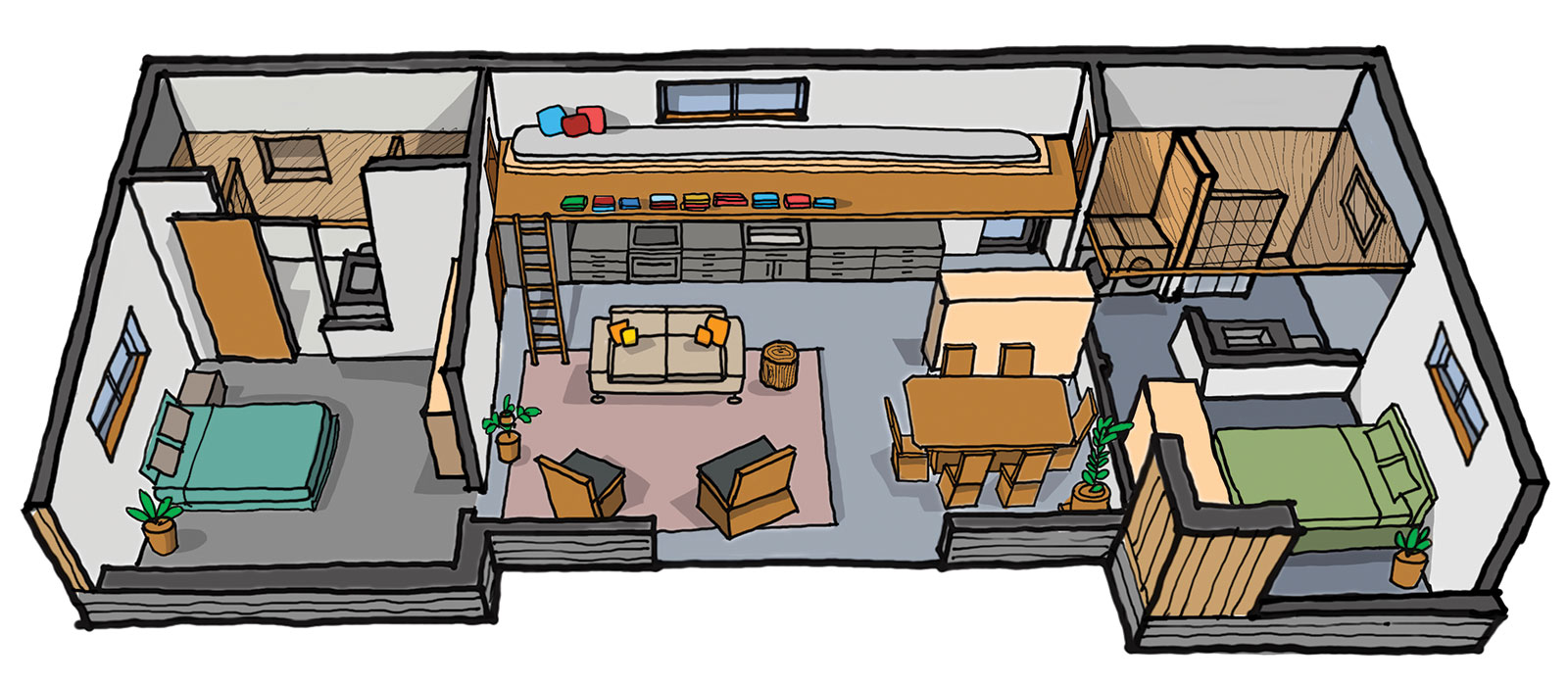

The house would be a demonstration home showing how to build with more sustainable, healthful materials; how to reduce waste; and how to maximize space in a modest footprint. It would be affordable and replicable. The informal open floor plan and modern sensibility, combined with rustic good looks and easy access to outdoor living, would appeal to retirees and young families alike.

Transitioning to innovative building

Showing the house would help me walk the walk, not just continue to talk the talk, as I tried to steer my business away from conventional construction and outdated design solutions and toward everything I believed in (but that wasn’t yet popular among most building professionals). If nothing else came of it, at least I’d have a cool place to live and work. I called my new side hustle, Poem Homes.

The connection between home design and the impact it has on the environment was made clear to me on the first-ever Earth Day in 1970, when we learned at school that a brick placed in a toilet tank would save water. A few years later, I joined the back-to-the-land movement and got to see—and live in—some of the earliest experiments in earth-sheltered and passive solar designs. For someone whose furthest horizons had been peddling around the cul-de-sacs of suburbia, this was heady stuff.

By the time I took my first drafting class, I could hit a 16d nail home in three strokes, cut a straight line with a circular saw, lay down a smooth coat of drywall compound, and in other ways make myself useful around a construction site. But with a growing family, an office job made more sense. After completing a two-year degree in architectural technology, I drafted for several architecture offices and then got my first real education by running estimates, placing orders, and working at my local lumberyard sketching out solutions to tricky problems for builders. After 10 years, I was ready to start my own design business, Amber Westerman Building Design, with a focus on custom homes and remodels for the delightful mix of farmers, artists, and transplants who make up my corner of southwest Wisconsin’s Driftless Area.

Sharing the build

If I was going to go through all the trouble and expense of building a demonstration home, I wanted to get as much attention for it as I could during the process, not just when it was done. I wanted people to see the bones and guts and understand the whys and hows of the methods and materials I was using—not just the finish work. The average person has few opportunities to step onto a job site, and I guessed it would interest them—whether they were looking for a new home or not—and if they followed my progress in real time, they might stay more engaged and tell their friends about it.

My marketing strategy was simple and cheap: I crowed about it to everyone I met and held frequent open houses, which I announced on Facebook, in our local monthly, and by pinning up flyers at local businesses. My first open house was on a chilly day in December. The roof sheathing was not on yet. Twenty-five people showed up.

Ultimately, I held 16 open houses and had 520 visitors. In addition, I showed the house privately to dozens more, some of whom became my clients. People asked good questions and each one helped me refine my answers. What they said gave me clues about what caught their eye, what they had concerns about, how much general knowledge they had about construction, and what they were looking for in a new home. I talked about the systems and products I’d spec’d and shared the design thinking behind them.

Assembling the right building team

As I anticipated, putting together the right team took work. I lined up contractors I had confidence in and reached out for recommendations to fill in the gaps. I enlisted a neighbor who runs a remodeling business to be on call should I need a “wingman” (I did). A few subs were willing to give a flat price, but I paid most of them by the hour. We made a great crew but for one: the framing crew I hired cut a lot of corners. I fired them when the roof underlayment they installed leaked like a sieve. Friends with skills stepped in to help, and I patched and pieced in carpenters and got the work done.

A few notes on paying subs by the hour: By-the-hour work is common here for “single-truck” workers, including those in the mechanical trades. I would do it this way again if I were doing it as an owner-builder and were able to be on the job site most of the time to monitor the work. If I were working for a client, I would need to have firm bids from each sub, or an estimate based on an hourly rate with a not-to-exceed number. I tell my clients that experienced general contractors are invaluable because they get competitive bids, keep their subs to a timeline, and are on the lookout for poor-quality work or materials.

I was lucky to be my own boss and to be on the job site almost every day. I didn’t have any deadlines, and I enjoyed all aspects of staging the work: ordering, pickups and deliveries, stacking and sorting materials, and deciding what to do with the waste. (For example, drywall cutoffs were tossed along a row of trees and covered with rotten straw; gypsum can improve soil structure.) I kept a daily log, took lots of pictures, and kept up with the bills and my construction blog at poemhomes.org.

Hours and expenses

I ended up doing more of the hands-on work than I thought I would—or could. For instance, I asked my tilesetter if he’d grout the control joints in the slab. Sure, he could do that. But when? Several weeks went by and I grew impatient. I watched some YouTube videos, figured out what type of grout to get, and hit it. As it turned out, many tasks were easier—though more exhausting—than I thought they would be.

In the end, my total cash outlay was $332,000, or $275 per sq. ft. (1208-sq.-ft. house + 400-sq.-ft. breezeway + 440-sq.-ft. two-car garage). This includes permitting and fees, the energy modeling and blower-door testing, utility hook-ups, the 7.32 PV system, appliances, plumbing fixtures, lighting, and final landscaping. The total does not include the lot, of course. It also doesn’t include any “carrying costs” (taxes, water, electricity, interest), my architectural plans, or my contractor fee.

This number also doesn’t include my “sweat equity.” I approached this project as an eager and above-average skilled homeowner (of course with above-average knowledge of the business), and not as a skilled or trained carpenter. I performed many tasks solo. Other times, I was a helper. I definitely did all the sweeping, sorting, unpacking, trash removal, and some pick-ups and deliveries. I put in 2080 hours from September 2018 to October 2020—here’s a breakdown:

- 36 hrs — Landscaping

- 126 hrs — Sub-slab vapor barrier, sub-slab foam, sealing and grouting the slab

- 572 hrs — Rough framing, window install, vent-chute install, air-sealing exterior

- 567 hrs — Drywall mudding, taping, and painting; install vapor retarder

- 260 hrs — Siding, porch finish, metal trellis

- 253 hrs — Building the loft

- 96 hrs — Cabinets and trim and fixtures

- 170 hrs — Electrician’s helper

- TOTAL: 2080 hrs

I’m proud of the design and the quality of work. My path forward as a general contractor isn’t certain, but my plan to build a demonstration house and attract environmentally aware clients to my design business is working. More people are getting the idea that a thoughtfully designed small home built with natural materials and in tune with the rhythms of the day makes for a quiet, comfortable, and serene life. That’s what a Poem Home is all about.

Photos by Beth Skogen, except where noted.

From Fine Homebuilding #307

COMPANION ARTICLES

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Code Check 10th Edition: An Illustrated Guide to Building a Safe House

Original Speed Square

Plate Level