Is Zero Energy the Answer?

Experts share their thoughts on the role of net-zero-energy homes in a climate-friendly future for residential construction.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This post is part of a series in Green Building Advisor’s Expert Exchange program. We will address a quarterly set of topics, the first of which was “Getting to Net Zero.” The net-zero-home series culminated with a webinar panel discussion among contributing experts.

Based on the information available, it seems safe to say that we’re not making enough electricity at home. Rooftop PV, along with utility and community solar installations could contribute 40% of our electrical needs by 2035 if costs keep dropping, if policies are favorable, and if we continue to electrify our buildings and transportation, according to the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Solar Futures Study. This will go a long way toward de-carbonizing our grid, says the DOE study. A 2016 study from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) predicts that we have the potential to cover up to 40% of electrical generation with rooftop PV installations alone. And according to the Solar Energy Industries Association, the hard costs of a residential PV installation are just over $1 per watt—the costs of panels and racking and inverters was closer to $5 per watt just a decade ago. While residential installations were on pace to have a record year in 2021, the U.S. Energy Information Administration says that solar will have covered just 4% of electrical generation in 2021, and will jump only 1% in 2022. We have a long way to go.

Not every existing house is right for a rooftop PV system—there is an ideal design. Some houses have too much shade or do not have a roof with an appropriate orientation, making it hard to justify the cost for minimal efficiency. South-facing roofs are best, and there is an optimal pitch for every roof (equal to the home’s geographic latitude), but east- and west-facing roofs can be used, as can a variety of roof pitches (or even flat roofs), with often minimal loss in panel efficiency. Soft costs also need to be considered. There is considerable labor involved in installing a PV system, and they can have high permitting costs and may come with fees from the local utilities. All of this, and the fact that there may be more cost-effective energy improvements to be made first, make installing a solar array on an existing house a tricky decision.

For new homes, designing for PV is a no-brainer, says architect Paul Lukez. In fact, that’s how he feels about the zero-energy equation and the potential for new zero-energy homes to be an engine for innovation. “Our existing housing stock is going to be with us for a long time. Thinking about how we convert that stock to be more energy-efficient is a huge challenge and a huge opportunity,” he says. “The value in focusing on new, net-zero, single- or multi-family homes, even if they’re only contributing 1% or 3% per year to our building stock, is that it brings much-needed focus and attention to this topic. It brings new ideas to the table.”

Net-zero-energy homes generate as much power as they need over the course of a year, a simple equation easily tracked through net metering as most zero-energy homes are grid-tied. Pioneers of the zero-energy movement tried a lot of things, like balancing an over-generation of electricity with fossil fuels burned on-site, and wind power, when PV was still relatively expensive. But today’s zero-energy houses have a more common model—all electric, with roof-top solar panels. Designers and builders have become so savvy at reducing loads that the amount of PV required to meet demand is often surprisingly little. That’s good, because electric vehicles are coming on strong, making a net-positive house even more advantageous than one that nets out at zero.

Most professionals who have designed and built a few zero-energy homes will say that all the knowledge and technology, as well as the products and processes needed to guarantee net-zero-energy in a future project are readily available. It’s easy to see zero-energy homes as a silver bullet for the home-building industry, and it’s part of a path toward a climate-friendly future, but there are always caveats. To get a better sense of the challenges, opportunities, and shortcomings of zero-energy homes, I asked a handful of deeply-experienced industry experts for their thoughts on a simple question, “Is Zero Energy the Answer?” The following short essays are their responses.

House-by-house, block-by-block, city-by-city

This begs three other questions: The answer to what? The answer for whom? And the answer at what cost? The what is climate change. To combat this, we must build and retrofit all buildings with net-zero energy as a baseline standard. The whom is humankind and nature. Without nature, humans cannot exist, so our base survival instincts must be redirected to save nature. And cost refers to how we assess the cost of losing our global civilization, incrementally or apocalyptically, by calculating the costs to rebuild damaged societies and ecosystems and the investments we can make to prevent such damage.

“Each zero-energy project will play a key role in building a more sustainable city.”

The scale of this challenge can be overwhelming, but it asks us what we can do as individuals, families, and communities to fight climate change. Building and retrofitting all structures and cities to net-zero energy is both effective and essential, for many reasons: It is easy to understand, imaginable, and easily branded, thus useful to the public. Its simple metric—you are either net-zero or not—makes it a tangible goal with bragging rights. Given the technological advances and reduced costs of renewable energy systems, it is increasingly financially viable. The body of design and technical solutions and knowledge is ever-increasing. No longer just for tree huggers, net-zero energy is something many people (especially millennials) wish to have as part of their lives. And finally, it is approaching a tipping point in the marketplace of ideas and products. Given how the electric vehicle has captured the public imagination, zero-energy homes can be next. Each zero-energy project will play a key role in building a more sustainable city: by making each household zero-energy, we can build more sustainable communities—house-by-house, block-by-block, city-by-city.

While this goal offers some stability in re-balancing the demands built structures place on finite natural systems, we need to go beyond zero-energy. Adopting a net-zero model is but the first step in reversing the trajectory of climate change so we can restore and heal our planet and its damaged ecosystems. To achieve this goal, we must consider regeneration. This requires converting our zero-energy efforts to energy-plus solutions. For example, each home should provide enough energy for its residents’ domestic and transportation needs, by integrating an EV charger into its renewable energy system. More broadly, regeneration pairs each humanly initiated design and physical intervention that impacts the earth and its resources with a means of healing and restoring parts of our ecosystems or re-balancing a vulnerable natural system—for example, capturing and sequestering carbon. Many more innovative solutions could help restore natural systems as well. This needs a radical re-conceptualization and transformation of how we live and how we design new environments and cities to return more to the earth than they use. Our accumulated debt to Mother Earth is large. It is time to pay it down through regeneration and for those of us working in residential construction, that starts with zero-energy homes.

Paul Lukez is principal at Paul Lukez Architecture / PLASES, a former professor of architecture (MIT), and the author of “Suburban Transformations.” His work has been published in Fine Homebuilding, and here on GBA.

Let’s get going

Buildings have an outsized impact on energy use, resources, greenhouse gas emissions, and by extension, the earth’s climate. A full 39% of all the greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. come from our buildings—more than from transportation or industry. On top of this, humans are currently building the equivalent of a city the size of New York on the planet once every 30 days. Fortunately, buildings have the potential to move from an energy-intensive enterprise to one that can be restorative, sequester carbon, and use no net energy. Buildings can even become energy producers themselves. The beauty of this is that it can all be done in a way that provides us with a better experience of our buildings—from health, to comfort, to resilience and safety. Zero-energy buildings provide us with the rare win-win in our collective fight against climate change with benefits to individuals, communities, and the planet.

Electrification is also going to play an important role in the future. All-electric homes avoid the perils of fossil fuel combustion to our health, environment, society, and safety. All-electric homes are also more efficient by orders of magnitude over homes with combustion appliances. Even the most efficient combustion appliance can only reach 98% efficiency. Heat pumps can produce upward of three times or more the efficiency of combustion equipment. Importantly, by electrifying our homes with on-site renewables, battery storage, and bi-directional charging from electric vehicles, we also leave the door open for a cleaner future electrical grid. Therefore, zero-energy homes also have the potential for a distributed and resilient grid that will be less affected by storms, geopolitical disputes, and unstable utility prices. All things that are portended for a future with rising global temperatures.

All that being true, there are some challenges to the wholesale uptake of these types of homes—from the way we build them to the way we live in them. People need to be aware of zero-energy homes and the benefits they accrue; there needs to be a demand created for them in the market. Many people haven’t experienced these homes and due to a concerted effort by industry, people have genuine questions about how they perform and may have a difficult time transitioning from gas cooking, combustion fireplaces, old perceptions of limited hot water, and uncomfortable electric-resistance heating, for example. People also have questions about things like power outages and how they can be addressed in all-electric homes.

“None of this is a technical problem looking for a high-tech solution.”

Builders and designers also need to shift the way they deliver these buildings. Architects will have to pay attention to things they historically had not considered or left for the trades to figure out on-site. Designing assemblies that take into account local conditions and that lower energy loads will become critical. Working in concert with builders to determine how these new assemblies and systems can be buildable and cost-effective will be key. Builders will have to adjust their order of operations and pay attention to control layers and how they intersect with a home’s windows, doors, and penetrations, as well as areas where two assemblies come together.

None of this is untenable or out of reach. None of this is a technical problem looking for a high-tech solution. We have the solutions and knowledge in hand right now to produce zero-energy, and even zero-carbon buildings. I know our industry is smart enough and creative enough to bridge the gap between how we are building now and how we must build in the future. It is just going to take willpower, education, and a focus on doing the best we can as an industry—something we already purport to do every time we speak to our clients about our work. It’s time to make this transition and do it in an equitable, efficient, and cost-effective way. Zero-energy buildings are the best thing our industry can do for a better future for all of us. Let’s get going.

Josh Salinger is founder and CEO of Birdsmouth Design-Build in Portland, Or., and a frequent contributor to Fine Homebuilding and GBA.

It’s a matter of time

I design zero-energy homes exclusively. I made that commitment when DOE developed their Zero-Energy Ready program 10 years ago. I realized that with some minimal requirements and goals, it was up to my clients, their builder, and me to achieve those goals. We could choose to use a mix of prescriptive or performance guidelines, as we saw fit. The DOE’s program isn’t about accumulating points and it doesn’t require paying exorbitant amounts of money to private organizations to register a project. It’s achievable and it’s all about performance.

“It is incumbent on us, the designers and builders, to make sure the home is also healthy to live in.”

I see zero-energy homes as the future, whether the industry likes it or not, as all building codes are going in that direction, some quicker than others, but it’s only a matter of time until we all have to go this route. The sooner the better, in my opinion. Yes, it’s great to save the planet or save on energy bills, but to me the most important reason to commit to building zero-energy homes is to give my clients and their family a healthy home, one which provides good indoor air quality, good environmental quality and ventilation, and clean water. A healthy home reduces volatile organic compounds, toxins and chemicals, humidity and mold, and electromagnetic field. Given what it takes to build a zero-energy home—the thermal performance and air tightness requirements—it is incumbent on us, the designers and builders, to make sure the home is also healthy to live in.

My personal objective as a zero-energy home designer is to weave beautiful aesthetics with function, conservation, air quality, performance, universal design, and sustainability to achieve the best home for my clients, and to minimize the impact on our natural resources. I want to help my clients achieve their zero-energy goals without breaking the bank and using unreasonable or unnecessary guidelines. I want my houses to reach maximum performance using realistic building practices and easy-to-buy materials and services.

In my line of work, experience counts a great deal. It’s imperative to be knowledgeable, stay current with the latest technology, systems, and processes, and to have connections you can call on, if needed. Unfortunately, our industry lacks a willingness to change to new and more efficient systems and methods, and there is no incentive for education, so it is up to me and my teams to be the guides and councilors. I make sure that each homeowner is 100% on board with the zero-energy guidelines and goals, so we can select a builder and subcontractors that are fully committed to following through with our design and construction processes. In a way, we have to start as a team, making sure we are all on the same page throughout the entire project. Without those commitments, we are all wasting everyone’s time and resources.

Armando Cobo is a zero-energy home designer working in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Fort Worth, Texas, and an Expert Member at GBA.

Bring the carbon home

Super-efficient homes are nice, and certainly an improvement over the leaky energy hogs we’ve been building for too many decades. But zero-energy is only halfway there, if that.

It’s a bit like mining towns out west. When it becomes clear that the mine tailings are poisoning the local river, there is an outcry and the mine shuts down. But the problem isn’t solved: there is still poison in the tailing ponds, slowly leaching into the river. You haven’t solved the problem until you clean up the tailings. Healing is more than ceasing to do harm, it necessitates restoration.

“Be just as obsessed with finding ways to bring the carbon home.”

We in the construction industry should aim to make every building we work on, be it new or old, into a clean-running machine that needs little or no external energy input. But we can do even better. Let’s swing for the fences here, folks, and durably bury carbon in every part of every project we work on. Use sustainably harvested lumber. Ask for, insist on, low-carbon concrete. Use cellulose, not plastic foam insulation. Pay attention to the refrigerants used in your heat pumps, pay attention to the carbon footprint of every product you use. Talk to your suppliers, hassle them, cajole them, into thinking the same way.

Zero is not the goal. Be insanely obsessive about reducing emissions, sure, but be just as obsessed with finding ways to bring the carbon home. Your children will thank you.

Bruce King is a registered structural engineer, founder and director of the Ecological Building Network, and author of The New Carbon Architecture: Building to Cool the Climate.

There are “buts”

Of all the new houses I’ve designed since 2015 almost every one of them has been either net-zero-energy ready, net-zero energy, or energy positive. I’m defining a net-zero energy home as one which produces just as much energy as it takes to run. (I know this is a simplified explanation and there are other ways to define these terms.) Because I now limit my new-home design practice to high-performance homes, and because in net-zero homes, reducing the amount of energy you need is critical, I haven’t installed a traditional fossil-fuel heating system here in Maine in more than five years. The people who hire me are specifically looking for a home that exacts a lower environmental toll than most homes in the U.S. currently do.

“It hasn’t taken much effort to educate our clients on the advantages of eliminating fossil fuels.”

Given the availability of high-performance products like heat pumps, energy-recovery ventilators, water-resistive barriers, and triple-pane windows, creating a healthy and durable building envelope for a home that needs minimal heat isn’t that hard anymore. Sure, it takes time, practice, education, and a healthy dose of respect for your craft, but it hasn’t taken much effort to educate our clients on the advantages of eliminating fossil fuels—with the exception of wood-burning stoves. In Maine, it’s hard to convince people to forgo them.

Other than some “heated” discussions about wood stoves, I don’t need to haul out my soapbox to tout the benefits net-zero homes. I can just talk about their comfort, security, resilience, and the emotional connection to the outdoors, which is a happy by-product of designing a sun-filled net-zero home.

All this is wonderful but there are several “buts.” Even if we could make every home (new and old) net-zero, our current electrical grid may be incapable of supplying the energy they would still need. Neither the grid nor at-home battery backup systems are up to the task of keeping pace with an all-electric lifestyle for more than a short time. With the grid, in some cases, the transformers and lines running into homes aren’t sized properly for the connections. In other cases, homes are underwired for the amount of electricity they will need to keep everything from cooktops to electric cars humming.

As we move toward electrification, we need to consider the larger infrastructure to support it, even as we push the market to come up with better off-grid solutions to meet individual energy needs. The need to be connected to energy grids isn’t going away anytime soon, but the more energy we can produce cleanly and sustainably on-site, and then store to power homes and vehicles, the easier it will be to move toward all net-zero homes.

Emily Mottram is the founder of Mottram Architecture, host of the E3 podcasts and the BS* + Beer Show, and co-author of the forthcoming Pretty Good House book.

A thousand opportunities

Zero-energy homes are a critical component of creating the de-carbonized housing industry required to ensure there is a future in which to continue building. In that the majority of a home’s lifetime greenhouse gas emissions result from the consumption of operational energy, creating a replicable model for zero-energy housing is a key strategy in addressing the building industry’s role in climate crisis mitigation and adaptation.

Co-benefits of comfort, durability, resiliency, and low operating costs all provide opportunities to address issues of social good and to provide safe, equitable housing for all. The housing crisis facing much of the country will inevitably increase in the decade ahead, as cities fall beneath rising sea levels and regions choke in fire smoke, leading to increased domestic and international ecological migration. Accordingly, zero-energy homes must be a standard for housing across a diversity of housing types, including retrofits and renovations as well as modular homes and housing developments, and not just a luxury afforded to the niche of new, detached, custom single-family houses.

Defining “zero-energy homes” is an important challenge and opportunity. Does this include source energy, or just site energy? Is there a limit to how much solar you can throw at a home? Is there a limit to the size of a house per person? Answering those questions will allow us to set appropriate metrics—for example, energy use intensity—that lead to sufficient change in regulatory, incentive, and overall market transformation. First-cost adoption and innovation are privileges of few, as a niche in the housing sector and all the more so for sustainable buildings. Now that concept has been proven both technically and in the marketplace, zero-energy homes need to become the standard of new construction across scale by improvement in building and energy codes and programs, and cost-effective enclosure, mechanical, and renewable energy design and construction practices.

“It is important to frame zero-energy homes as a critical component of achieving a de-carbonized industry, and not a goal unto itself.”

Market education and development is an ongoing effort to energize this transformation, so green buildings are not just contributing to eco-gentrification. Likewise, regulatory and incentive programs being developed in response to climate action plans must ensure that equity is centered in the strategies for how the transition to improved buildings standards is being implemented, from investments in low-income weatherization programs to financing programs supporting marginalized communities—for example, anti-redlining community investment programs.

From a practical perspective, high-performance, low-load mechanical design and trade support is in huge demand right now. More and more builders can build thermally-efficient enclosures, but getting the HVAC right is another level of work that is not well enough supported in the industry. Increased cooling demands due to both a changing climate and the ubiquity of heat pumps requires that heating-dominant region professionals need to skill up. There is also not enough equipment available to adequately turn down to part-load conditions efficiently and effectively. Further, the resiliency implications of requiring a generator to power critical building loads, until bi-directional EV charging provides sufficient battery backup for heat pump compressors and big resistance coils, need to be better considered as we must design for climate crisis adaptation as well as mitigation.

The issues of equity in representation and access to the increasing number of jobs in the renewables, engineering, design, and construction fields, as well as residency and ownership of these homes, are a consistent challenge to be addressed in each part of the puzzle.

Finally, all-electric buildings require integration with infrastructure that itself is still in development. Not only bi-directional EV charging, but load-sharing across regional grids and other forms of infrastructure integration must find its way into our homes as part of a very large effort to expand grid distribution, storage, and capacity to allow for the housing sector to convert fully to being all-electric powered by renewable energy. This includes the development of regional grid infrastructure and renewable generation capacity as well—it’s all connected!

More than anything, it is important to frame zero-energy homes as a critical component of achieving a de-carbonized industry, and not a goal unto itself. Disregarding other phases of greenhouse gas emission and looking to energy reduction as a primary metric can easily result in unintended consequences of large, immediate plumes of greenhouse gas emissions through the use of greenhouse gas-intensive insulation materials, let alone the rest of the materials in the building. Considering the embodied carbon emissions of materials being produced today, as well as the potential of buildings to store carbon in their materials, we need to set goals and metrics based on carbon-use intensity, not just energy consumption, to ensure the net impact of our efforts is truly in service to the climate.

While I attempted to address the social impacts and effects of zero-energy home development along the way, it bears mentioning again that zero-energy homes are not just a technological innovation; the goals set for scaling up these homes to address the extent of energy reduction necessary in housing requires everyone to have access to these homes, and everyone to participate in getting them designed and built. Accordingly, considering how we make zero-energy homes happen quickly at scale requires reducing barriers to access to technology, capital, education, and training. This shows up in a thousand different ways, from revitalized vocational training programs integrated with STEM curriculum, to design and construction training, to new financial programs to incentivize green business startups, and much more. There are a thousand different opportunities to match these challenges, and we will need them all to achieve the goals required of us to build long into the future.

Jacob Deva Racusin is the studio director and director of building science at New Frameworks. He is the author of “Essential Building Science” and co-author of “The Natural Building Companion” with Ace McArleton.

The future we envision

Our firm, ZeroEnergy Design, strives toward a socially just and equitable world where buildings make positive contributions to the environment. We envision a status quo of energy-positive, carbon-neutral buildings, made of biodegradable and recyclable materials. We engender love through creating spaces that are beautiful, functional, durable, and provide healthy, comfortable environments.

This is the future we envision. The current reality is the buildings account for 28% of the annual global CO2 emissions. Building materials and construction account for another 11%. That’s 39% of the global CO2 emissions. If we look at energy use specifically, 22% of global energy use is attributed to the residential sector. Net-zero-energy-ready homes are an instrumental part of building future.

“The homeowner can be a bit of a wildcard in terms of energy-use habits.”

Our approach to a net-zero-energy-ready home is to reduce heating and cooling energy use by prioritizing the home’s enclosure. This allows us to drive down heating and cooling energy, rely on small all-electric systems which decouple the home from fossil fuels. Efficient lighting and appliances complete the package. The homeowner can be a bit of a wildcard in terms of energy-use habits, but we advise on the optimal way to live in the home, install a simple energy monitoring system, and hope we’ve done our part.

This low-load, all-electric home is net-zero ready. Many of our clients put a solar array on the roof on day one. Whether they do or not, our goal is to make sure that the roof is designed for one. The solar infrastructure can then be easily installed and there’s sufficient roof area for an array that will offset the home’s energy use over the course of a given year, making it net-zero-energy. And, we suggest that our clients oversize it, making it net-positive, to allow them to charge electric vehicles.

This approach is not rocket science. The materials we specify are readily available at the local lumberyard, though we sometimes rely on less commonly accessible materials to drive down embodied carbon and reduce reliance on fossil fuels. Similarly, the details we employ are available through resources like Green Building Advisor and Building Science Corporation. It’s not proprietary—it’s out there for anyone who is interested. As practitioners, it is our choice to advance our details and standards rather than rely on practices that are 10 or 20 years out of date. We hope that others will make the same choice.

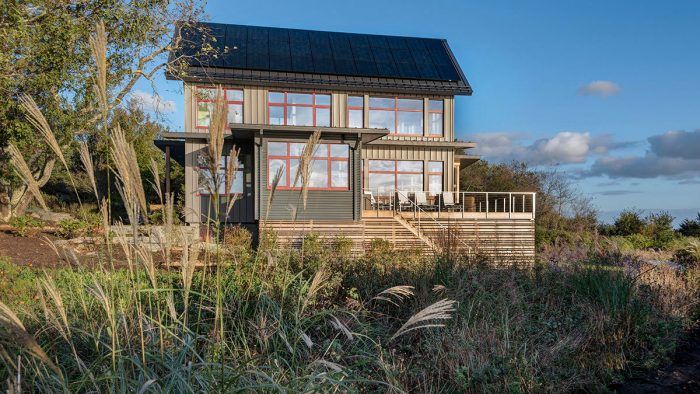

Photo by Nat Rea. Originally published on GreenBuildingAdvisor.com.

Architect Stephanie Horowitz is the managing director at ZeroEnergy Design. Many of their projects have been published in Fine Homebuilding and on GBA.