How to Get Sturdy Walls Without OSB

Fernando Pagés Ruiz discusses how he omitted the OSB on this spec home to save money, while still making sure his build had reliable structural quality.

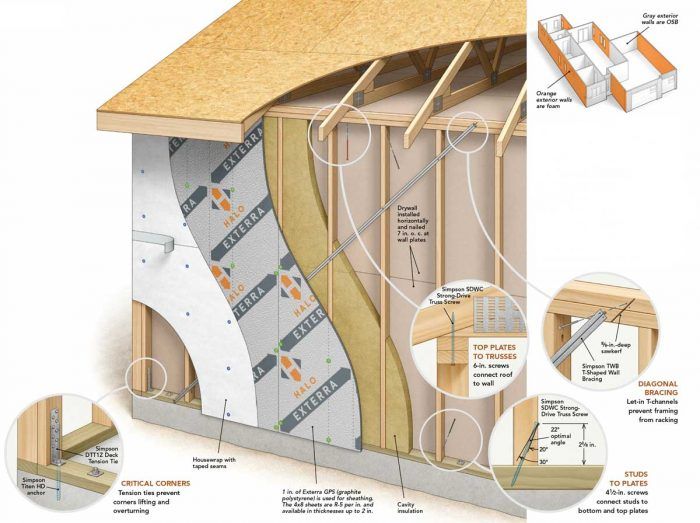

Synopsis: The fluctuating cost of OSB and plywood can be a motivator when it comes to omitting structural sheathing. Sheathing a house without plywood or OSB involves figuring out how to achieve resistance to uplift and racking, how to install siding without backing underneath, and how to get a warranty for windows installed on foam. Builder and ICC-certified residential building inspector Fernando Pages Ruiz discusses how he omitted the OSB on this spec home to save money, while still making sure his build had reliable structural quality.

I’ll admit that my recent motivation to omit structural sheathing was cost. The price for building a 2×6 exterior wall on 24-in. centers sheathed with OSB shot up nearly 500%, and ready alternatives such as Zip System and Ox Thermo Ply were back-ordered.

Sheathing a house without plywood or OSB involves three primary considerations: how to achieve resistance to uplift and racking, how to install siding without backing underneath, and how to get a warranty for windows installed on foam. Recently I was able to solve all three problems and save a total of $2,755 on an affordable spec home I built.

In addition to costing less than OSB or plywood at present, continuous exterior foam insulation slows thermal bridging through framing members, adds an R-value of R-4 or R-5 per inch, and simplifies vapor control. In my case, 1-in. of R-5 foam with R-15 cavity insulation performs better than a 2×6 wall with R-19 cavity insulation.

Many high-performance builders add continuous exterior foam over plywood or OSB sheathing; foam insulating sheathing (like Zip R-Sheathing) is another option that makes installing continuous exterior insulation over sheathing a one-step process. But I intended to omit OSB to save money. Here’s how I did it.

A sturdy house without a structural skin

Removing solid sheathing requires structural improvements to prevent wind from lifting the roof or pulling the house from its foundation. You also have to beef up the walls to prevent racking, which is when the house tilts laterally under the power of wind or earthquakes.

In other words, to avoid building a house of cards, your structure must have connections that transfer the gravity, wind, and earthquake loads from the roof, through the walls, and into the foundation. Engineers refer to this as “load path.” Solid sheathing—or creating a rigid box with plywood or OSB on all the exterior walls—is a sturdy, simple, and forgiving way to achieve sufficient load-path connections and racking resistance. Nowadays, it’s also expensive.

Fortunately, the residential building code provides several methods to design and construct strong walls with various methods of bracing that add stiffness to the structure. I counted twelve different braced-wall panel types in the IRC, ranging from let-in diagonal bracing, to wood sheathing and fiberboard, to gypsum wallboard.

It takes a little head-scratching to design a braced-wall system that omits solid-wood panels. The code is cumbersome, and I had to lean on my friend Jay Crandell, PE, to help me, despite relying entirely on the prescriptive methods in the IRC. A warning is due. My design made things easier because it’s a single-story house, mostly square, and not in a hazard area—no hurricanes or earthquakes to complicate things. This article is specific to my build, but the techniques are within the grasp of most builders and structural engineers in low-risk parts of the country and they can be adapted for two- and three-story homes. Each building requires an individual braced-wall design strategy. What I did may not apply to your project.

Structural connections for a strong wallCorner hold-downs, long screws at top and bottom plates, and additional screws through top plates into the trusses complete the load path that keeps the house together during high winds and earthquakes. The author sheathed critical walls for additional strength and sheathed the gables to make siding easier. Diagonal metal bracing holds the walls square during construction. |

The problems with diagonal braces

One time-tested and code-honored option for walls without wood sheathing is 1×4, let-in wood braces, but they must be installed at the correct angle (45° to 60° from bottom to top plate) and fit with the precision of cabinet joinery to work properly. If the notches are too deep or too wide, or the nailing is off, the wall won’t work as designed.

More importantly, this option met with strong resistance from my framers—they had never done it before. Builders often neglect one key aspect of let-in bracing, which is that the wall must have 1⁄2-in. gypsum drywall on the interior face using a tighter-than-normal nail spacing.

One carpenter suggested using T-shaped steel braces like Simpson Strong-Tie’s TWBs because they’re easy to install—just slide the T-brace into a 5⁄8-in.-deep cut made with a circular saw and nail it. Many builders mistakenly use these as a direct replacement for let-in wood bracing. Unfortunately, when you dig a little deeper you learn in the manufacturer’s instructions that T-shaped braces are “designed to resist racking during construction.” In other words, they’re only meant to keep walls square while framing them, so we still needed a way to satisfy the structural needs of the house.

Jay Crandell is a structural engineer specializing in light-frame wood construction; he offered a solution that didn’t rely on diagonal bracing. He suggested hold-down connectors on the building corners, structural screws connecting levels, and additional drywall fastening to make up for the strength lost by omitting plywood or OSB sheathing.

Drywall helps control racking

Canadians and New Zealanders are far ahead of us when it comes to using drywall as a structural panel. Their extensive testing, and later testing done at the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB), revealed the structural power of 1⁄2-in. drywall. The results of the tests were convincing enough that the Canadian Building Code considers gypsum bracing on par with exterior wood sheathing, and eliminated the solid-sheathing requirement for much of Canada.

The International Residential Code (IRC) also recognizes gypsum board brace panels, although builders seldom take advantage of the potential added strength they offer. Unfortunately, until the drywall goes up, unsheathed walls remain vulnerable to racking, so I installed those T-shaped metal braces to hold things nice and square—precisely what these braces are designed to do. This also allowed me to complete the rest of the wall-bracing system myself after the framers left, and I didn’t have to deal with their grumbling or extra charges. Of course, drywall is not a panacea. We still needed to anchor the walls to the foundation at key points and connect all the framing from mudsill to trusses.

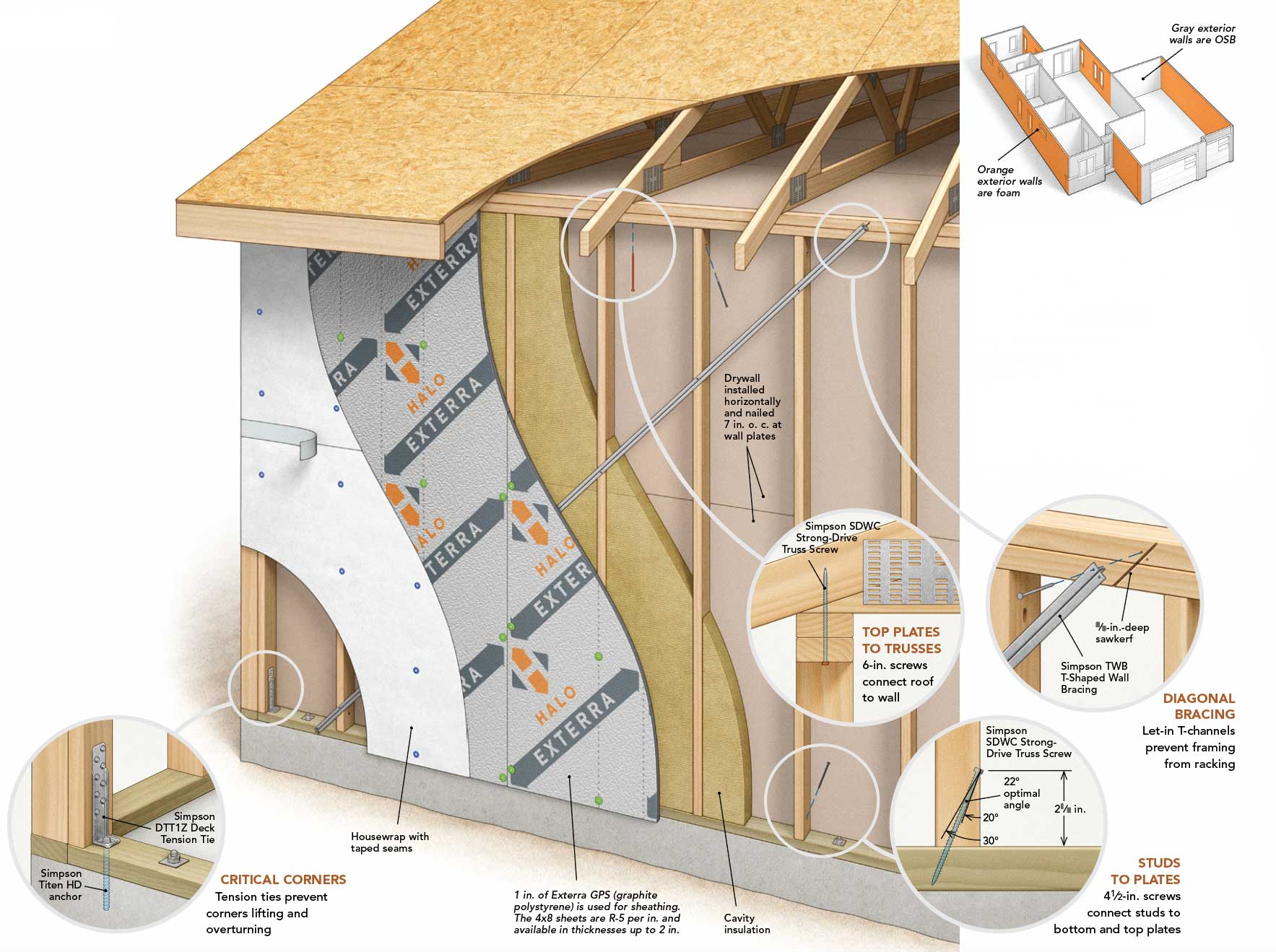

In California, drywall hangers are familiar with shear-wall nailing and even having their installation inspected before tapers move in. In the Midwest, where I build, it’s best to ask for a day between hangers and finishers to install the extra nails yourself. It’s not difficult to do. The basic code-prescribed pattern requires driving nails or screws every 7 in. into horizontal panels at the bottom and top plates. You don’t have to do any special nailing in the field or at panel joints because tape and compound sufficiently transfers loads between sheets.

Hardware completes the load path

The conventional way to connect exterior wall corners to the foundation is with concrete-embedded bolts that attach to the wall framing, but it’s difficult to wet-set the anchor bolts exactly where they belong. Jay suggested we use Simpson’s DTT Tension Ties. Although these connectors were designed to meet code requirements for connecting deck joists to a supporting ledger, you can also use them on building corners to prevent uplift. The advantage of the Simpson bracket is that you can install it exactly where you

need it after the framing is done using a Simpson Titen HD Screw Anchor.

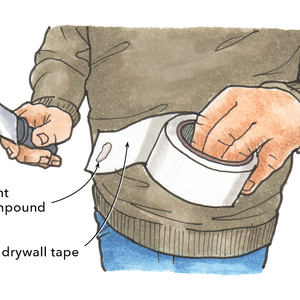

To complete the load path, Jay recommended using Simpson SDWC Truss Screws to securely attach the roof and walls. Similar products are available from other manufacturers. The screws, driven through the top plate into each truss, and then from each stud to the top and bottom plates, connect the roof to the foundation. One laborer can connect all the elements in a house like mine in a couple of hours.

Sturdy walls without wood sheathing continuedHold down cornersWithout a plywood or OSB skin, houses with foam sheathing need additional uplift resistance on corners that connect the frame to its foundation, otherwise the frame could lift or overturn in high winds or earthquakes. Some hold-downs connectors require a perfectly positioned anchor bolt that’s wet-set or cast in place during the slab pour. It’s hard to consistently get cast-in-place bolts perfectly positioned, so we used Simpson’s DTT Tension Ties (DTT1Z) installed after the framing to ensure they’re in exactly the right place. (These connectors are more commonly used as tension ties in deck construction.) The 5-in. screw anchor requires a 5-1⁄4-in.-deep hole, so we mark the drill bits with tape to ensure the holes are the proper depth. After drilling, the hole is cleared of dust with compressed air and we lubricate the screw with a little oil before driving it into the hole. The manufacturer’s instructions tell you to use hand tools or a drill—no impact drivers. The screw anchor must be tightened to 100-ft.-lb., tighter than a drill can achieve and tighter than intuition would suggest, so we use a torque wrench. Then six 1⁄4-in.-dia. by 1-1⁄2-in.-long Strong-Drive SDS Heavy-Duty Connector Screws, which are not included with the connector, attach the tension ties to the studs. The hold-down and screw anchor provide more than the required 800 lb. of uplift resistance.

Strengthen plate connectionsStrong-Drive 4-1⁄2-in. structural truss screws (SDWC15450-KT) connect the studs to the bottom plate and double top plate. These long, self-drilling screws help strengthen the connections between studs and plates and prevent the frame’s structural elements from separating when subject to sliding or uplift forces. The screws come with a T30 driver bit and guide that helps position the screw at the optimal angle. We used it for the first few screws until we felt comfortable eyeing the angle and driving the screw without it to save time.

Hold down the roofStrong-Drive 6-in. structural truss screws (SDWC15600B-KT) are used to tie the roof trusses to the top plate and help keep the roof connected to the walls during high winds and earthquakes. You can also use several types of metal truss connector for strengthening this vulnerable connection, but the screws cost less and install faster. The roof trusses have a 24-in. spacing and the wall studs have a 16-in. spacing, so with this roof’s simple geometry, the trusses land directly over a stud every 4 ft. The screw is angled when the truss is over a stud. Drywall resists rackingThe Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation and NAHB testing show that 7-in. on-center fastening at the top and bottom plate helps gypsum wallboard significantly increase a wall’s racking resistance. The contribution varies with panel orientation and wall length. Panels oriented horizontally are more than 40% stronger than those with panels oriented vertically and drywall nails are slightly stronger than drywall screws because they’re less brittle. For drywall used as bracing to be effective, the drywall must be taped and finished. Walls finished with high-strength setting-type compound can have 50% more shear capacity than those finished with a drying-type compound. Even greater racking strength can be achieved with taped drywall and a 4-in. fastening schedule. |

From Fine Homebuilding #309 as “Sturdy Walls Without Wood Sheathing”

RELATED STORIES

View Comments

I noticed that the foam sheathing did not have the joints between sheets taped. How do you control the entry of bugs, pollen, and any other exterior contaminants? Don't say the WRB because that is pure nonsense. Without a solid base how do you get the WRB to adhere to the foam board or do you use a peel and stick that is more costly?

Good to know that the metal T bracing is not meant for a sheathing replacement.

I wonder though if 1/4 inch exterior grade plywood could suffice? It will surely make for a better barrier to unwanted things getting into the building. Plus the seams and edges where the sill plate and foundation meet as well as where the panels meet, can be better sealed.