Paying Homage to a Quintessential Cottage

A heritage property in the Adirondacks maximizes indoor-outdoor living space.

Synopsis: When the owners found out that renovating the original 1940s kit-built house was no longer an option due to structural failures and moisture-related issues, they commissioned a 2775-sq.-ft. home to take its place in the town of Lake Luzerne in upstate New York. Their goal was to pay homage to the original house and occupy a similar footprint, while incorporating bigger rooms, higher ceilings, and an upgraded and retrofitted woodstove. Green Building Advisor’s Kiley Jacques details the design and siting of the home and how the build team ensured proper drainage at the bottom of the hill and designed an exposed floor system in the ceiling of the kitchen and dining room.

Specs

Bedrooms: 4

Bathrooms: 4

Size: 2775 sq. ft.

Cost: $456 per sq. ft.

Completed: 2018

Location: Lake Luzerne, N.Y.

Architect: Balzer & Tuck Architecture

Builder: Teakwood Builders

Completed in the spring of 2018, this 2775-sq.-ft. home is located in the town of Lake Luzerne in the Adirondack Park of upstate New York and is the result of a collaboration between homeowners Jeanine and Ron Pastore, architect Brett Balzer of Balzer & Tuck Architecture, and Jim Sasko, principal of Teakwood Builders.

For three generations, Jeanine’s family spent summers enjoying the lake “camp” house that formerly occupied the wooded lot. Her grandparents bought the original kit-built house in the 1940s and gradually added a porch and other updates over time. Letting it go wasn’t an easy decision, but the old house had reached the point of no return due to structural failures and moisture-related issues. Renovation wasn’t an option, so they demolished the old structure to build new.

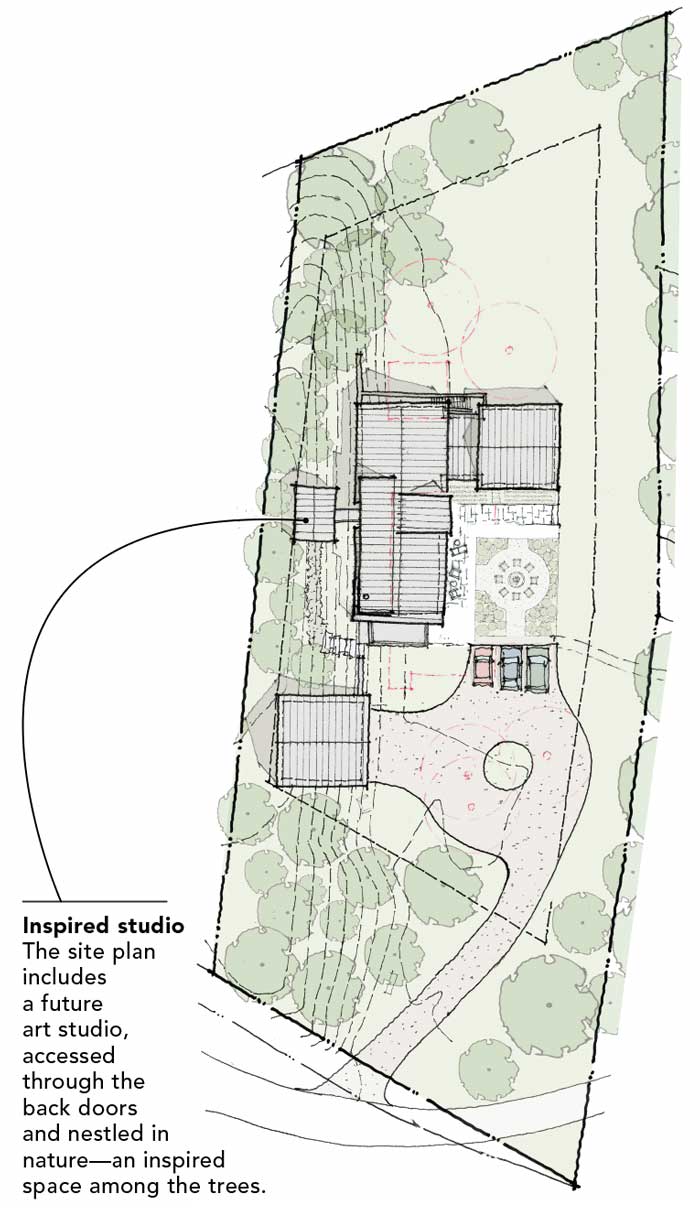

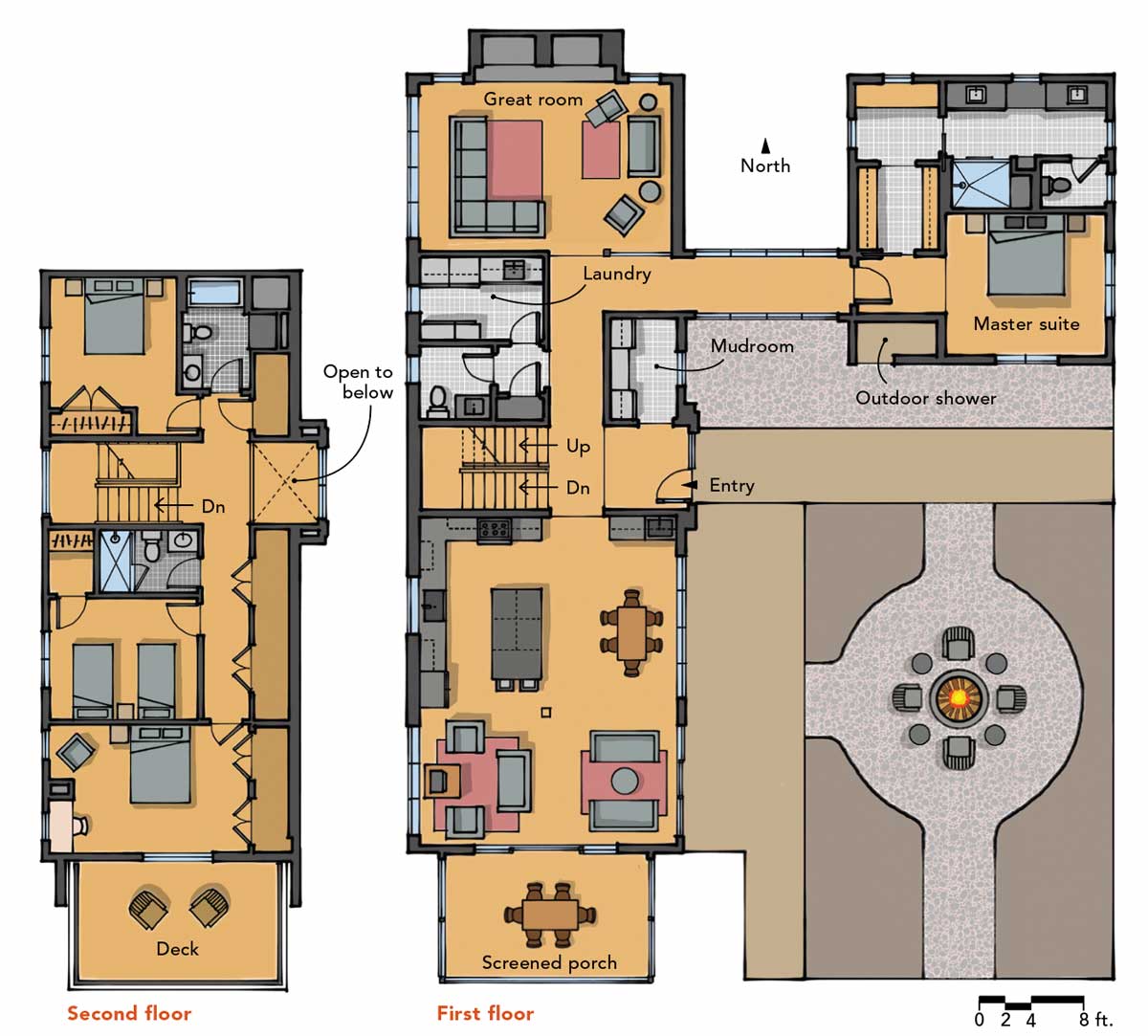

A site to beholdTo take advantage of the entire site, the home was built next to a hill, which meant thorough waterproofing was needed to manage water runoff at the base of the foundation. In addition to waterproofing the assembly, the design team added a stone drainage swale along the entire length of the house to minimize runoff. An indoor–outdoor planThe floor plan is designed to connect indoor and outdoor spaces easily, with the kitchen and dining room opening up to the courtyard. The staircase creates a visual separation between the public and private spaces within the home. |

The goal was a highly functional building that would house and entertain many generations to come. It needed to work on multiple levels, and paying homage to its predecessor was a primary goal. Jeanine and Ron also wanted it to occupy a similar footprint to the original. Other priorities included bigger rooms, higher ceilings, and an upgraded and retrofitted woodstove, which had been the centerpiece of the old house and is an important relic to the homeowners.

The team studied the existing house as they planned the new one. They wanted to recreate what they termed its “quintessential Adirondack lake cottage” charm. Jeanine, an artist, requested a mix of painted walls (for displaying artwork) and natural Douglas-fir walls, as well as fir beams and rafters, which were all treated in a clear stain to lend warmth to the rooms. The window frames were clear-coated rather than painted for the same reason. “Those were cues taken from the original camp,” notes Brett. “We wanted to have that warm feel of undressed timber.”

They also left the second-story floor-joist system exposed over the kitchen and dining area, which was a nod to the original camp’s rafters. Jim describes that part of the program as something of a puzzle. Above the kitchen and dining area are two bedrooms, a closet, and a bathroom.

“We thought the bathroom couldn’t be above open joists,” he says, explaining that the solution was to shift the bathroom fixtures around so they would all be up against the stairwell wall, where they could hide the shower and sink drain lines. All of the plumbing is located in a special section of 2×6 wall. (The rest of the framing is standard 2×4.) For the shower drain, they designed the upper kitchen cabinets to mask the P-trap.

“We saw that the stove would be on the same wall as the trap, so we needed to ensure that the stove wouldn’t move,” notes Jim. “It’s ducted up and out and is hidden behind those same upper cabinets.”

Jim also notes their handling of the floor system. Originally, the design called for a thin layer of edge-and-center bead over the floor joists of the exposed ceiling in the kitchen and dining area. Instead, they increased the thickness to 3⁄4 in. and laid a built-up floor on top of that, resulting in an extrathick floor across the exposed structure. This helped when putting in hardwood flooring nails; there was plenty of stable material to nail through.

Other puzzle pieces included the site itself. The original house was tucked up close to the edge of the woods at the base of a hill, which meant runoff ran straight to the foundation. When rebuilding, Jeanine and Ron were desperate to get away from that hill.

“But as we worked through the design,” Brett recalls, “we kept pushing the new house back toward the hill. It became a mental hurdle that everyone needed to get over. We knew that we could build next to or into the hill and keep water out. Putting the house back there would allow us to open up the site for a courtyard.” The solution included a foundation-wall waterproofing system with a fluid-applied membrane to protect the concrete. A drainage mat was installed over the surface to relieve any hydrostatic pressure while allowing water to move along the wall to a new foundation drain, which then directs the water to a remote dry well. They also put in a stone drainage swale along the entire length of the house. Plus, half-round Galvalume gutters capture and redirect all of the roof runoff before it reaches the rear of the house.

Given the ways in which the property is used, the courtyard was key. The community is very close-knit, with multiple generations of families growing up and socializing together. That communal lifestyle figured heavily into the design of the indoor-outdoor connection. The doors to the kitchen and dining area all open to the courtyard to accommodate space for large-group gatherings.

Another important element was the entry; the clients wanted a bit of protection and to introduce the timber that would feature throughout the house. “The big move there was to get the height for the stair once you get inside,” explains Brett, adding that the stair hall receives nice warm light that plays along the walls—something the homeowners have come to love. “The irony is that they didn’t want a staircase on display,” says Brett. “But it became the element that stitched everything together between the public and private spaces.”

The stair is poised to be inviting for another reason, too. Off the midlevel landing, a set of doors will eventually open onto a bridge leading to Jeanine’s Japanese teahouse–inspired art studio, which will be tucked into the hillside.

Improved functionality makes the new house a well-used, well-loved place. In fact, family members find themselves spending more time there than they had at the previous house. But it’s the fact that the old camp’s spirit persists that makes it really special. “Visitors often say that it feels like the old camp,” Brett muses. “That’s the nicest compliment we could get.”

Kiley Jacques is senior editor at Green Building Advisor. Photos by Susan Teare. Floor-plan drawings: 07sketches/Bhupeshkumar M. Malviya

From Fine Homebuilding #309 as “A New Build With Sentimental Charm”

RELATED STORIES

View Comments

The most livable space in this house is the Screened Porch. Anyone that has spent any time at all in the Adirondacks knows that the bugs are merciless. In order to enjoy the beautiful fire-pit, one must spray all exposed skin with repellent and probably bundle up for the chill at the same time.