Are 2D Drawings Obsolete for Home Building?

Using 3D modeling software instead of 2D drawings to share all the details of a home's construction avoids misunderstandings.

I design custom houses with a lot of detail. I always struggle to figure out what a set of drawings should include. Drawings are essentially a set of instructions to the builder explaining what the end product should look like and how to get there. If only it were that simple.

The first problem: Who is the builder? The level of expertise and familiarity with particular details can vary widely amongst builders. Should the drawings be targeted to the least or most experienced? Some details and notes that would be insultingly obvious to some might be a welcome explanation to others.

The larger problem: 2D drawings are an inherently inefficient way to illustrate 3D objects. The convention of plan-elevation-section exists as the time-honored workaround to this problem. We can’t see depth in an elevation, and we can’t see height in a plan, but if we combine both with a section we can get an idea of what is going on. This involves paging back and forth in the drawings and constructing a mental image of the 3D space, a cumbersome and error-prone process.

Finally, we have the problem of scale. Unlike boat building, where drawings are often actual size, house plans are drawn at scale, typically ranging from 1⁄4 in. per ft. for plans to 3 in. per ft. for fine details. Given the practical limitations of paper size (24 in. by 36 in. for a typical large drawing sheet), the scale at which one can see a section of the whole-house plan is much too small to make out any detail. Those details are shown at a larger scale on another page, and references must be made to connect the small- and large-scale drawings. This involves more paging back and forth in the set of drawings. To further confuse matters, large-scale sections utilize break lines to indicate that unimportant parts of the drawing have been removed, but this means we can’t include dimensions that span the broken area.

Because of the complexity of house construction, no single view contains enough information to completely describe the building elements. For example, an elevation may show alignment of two fascias, but it doesn’t show the framing behind the fascias, which may be different depending on the location. The builder must look at the elevations, then compare the various sections to get the proper alignment. However, a section might not have been taken at the particular area of interest. The builder must then reference the framing plan and try to infer from that and the other sections how to construct this particular area. It’s a lot of effort with lots of potential for misunderstanding.

On the design side, I spend (waste) a lot of time arranging details on the various pages so that they both fit on the page and have some logic to their arrangement, and the contractor spends (wastes) time paging back and forth trying to piece the whole puzzle together. It’s tempting to create very comprehensive drawing sets that address every condition, but this can be cost-prohibitive for the client. Even worse, sometimes large drawing sets are overwhelming to the builder, which can lead to higher bids or the builder simply ignoring some parts of the drawings. Conversely, creating a “lean” drawing set that would be more digestible for a builder can lead to construction errors.

The bottom line is that the standard method of printed drawings is inherently confusing, provides an incomplete picture of the project, and imposes a time cost on all parties. It may be time to scrap the system and take a leap ahead.

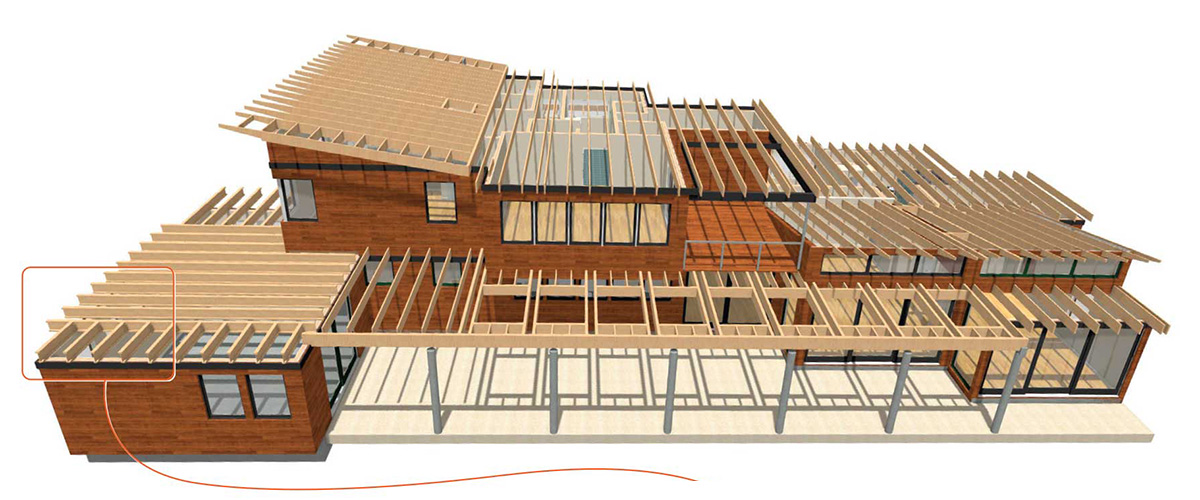

I use Chief Architect, an object-oriented design program, but any similar 3D-modeling software would serve the same purpose. “Object-oriented” means that the design is a 3D computer model that contains all the same elements (doors, walls, rafters, etc.) as an actual house. Rather than drawing lines, I draw walls, roofs, and more that contain all relevant building information—studs, sheathing, interior and exterior finish, insulation, etc. Any view of this model can display those elements.

The key benefit of 3D models, besides visualization, is accuracy and mistake prevention. When hand-drawing or using 2D CAD software, the designer can “cheat” and draw things that work on paper but not in the real world. Three-dimensional modeling forces the designer to figure out the details, and mistakes can easily be discovered in the design phase.

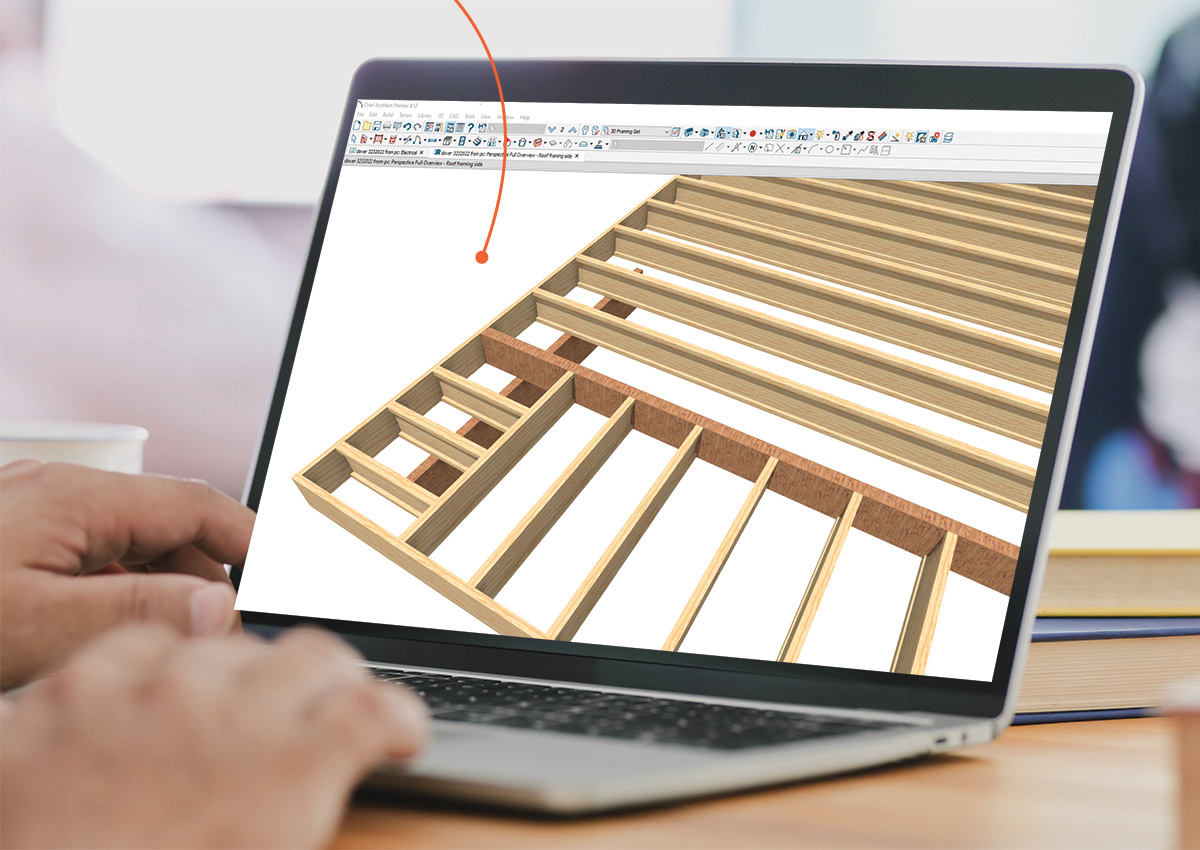

Rather than design in 3D and then produce selected 2D drawings of the model, I’m currently experimenting with simply giving contractors the design in the form of a 3D computer model, and letting them find whatever information they need within the file by viewing it on their computers or tablets. This offers many advantages over producing a set of drawings. By having the entire building model, the builder can find all the information needed by zooming into different areas without having to page back and forth between drawings. They can easily tab from plan to elevation to section, or do a split screen with the 3D model in one view and the plan in another. To understand how a particular roof is supported, they can display only the framing layer and see the bearing path from foundation to rafter. The builder can also create specialized drawing sets for the subcontractors, with relevant layers turned on or off.

This ability to create specialized layer sets for different aspects of construction allows important information to be delivered in context. Printed drawings often become very cluttered with notes, given the limited physical space on a drawing. Digital models have no physical limitations, and notes are linked to relevant layers. Information that would often be siloed is now available to everyone, but on demand, not cluttering the drawings.

Estimating materials is made far simpler with 3D models. Many programs can generate impressive material lists with a single click, saving hours of measuring drawings while doing takeoffs.

Tracking design changes is also simpler in the digital world. Models can be stored on a shared drive, with notification sent to the contractor when new versions are uploaded. Changes can be highlighted in a variety of ways. Rather than the traditional method of issuing SK detail drawings, which must be attached to the plan set and noted on the drawings, digital files can easily reference the existing and revised details for comparison. That said, making sure everyone is using the latest drawings requires clear communication, even in the digital world.

This transition from printed drawings to 3D-model sharing will happen gradually. Many architects still design in 2D CAD. While there is some limited benefit in sharing these types of files, the 3D model contains far more information than the 2D, which is more akin to paper drawings. The generational shift to 3D modeling as the primary design tool in most firms is well underway. New technology that allows existing conditions to be scanned and fed directly into 3D-modeling programs creates far more accurate drawings in hours, rather than days.

What are the drawbacks? Architects may be concerned about providing their designs in a digital form that could be reproduced and sold by other parties. I put clearly stated copyright provisions and watermarks within my models to discourage this. Many builders will be concerned about the learning curve of using software to navigate a model. This investment in time will be more than offset by the many benefits that come from being able to visualize all aspects of the construction. The language barrier is a problem in the trades, and 3D imaging ensures everyone is on the same page. “A picture is worth a thousand words” is understood by every carpenter who has drawn a detail on a scrap of 2×4.

This approach is not for every builder—it will be most useful to high-end builders on architect-designed projects. I prefer to work with builders using this approach, as it reduces my costs in design hours. More importantly, I know that critical details in construction are not missed because of misunderstandings with the drawings. By building the house in the model, the designer is forced to figure out all the tricky intersections and details, and the builder can visualize all these details and provide feedback to the architect before construction begins. Everyone having the same comprehensive picture of the construction at the outset and throughout the project leads to higher quality, lower costs, and less finger-pointing due to miscommunication.

Designer David Hornstein is a principal at Light House Design in Sudbury, Mass.

Drawings: courtesy of the author

From Fine Homebuilding #310

RELATED STORIES

View Comments

Great article, thank you!

I've been using Bim software (ArchiCad) for 15 years in my practice.

I've trained my contractors to navigate the software..(ArchiCad can send out design package/information that does not require the full program )..now they don't want paper.

I often involve the builder at the schematics and am able to iron out details early in the project.

The contractor is also up to speed when the construction actually starts.....win win for all.

I've also been slowly introducing colour and 3D details into my Permit Sets...so far so good! , long live PDF's and bye bye paper.

A few years ago I had a large renovation done on my old house. The architect measured the existing house very accurately, resulting in some nice as-built drawings, as well as views of options for the renovation. It turns out all of the work was done in Chief Architect, but the final work product was all conventional drawings, the typical 24x36 sizing. My conclusion is that software like Chief can automate and make the production of the the typical work product much simpler / cheaper (although there is a learning curve). That's before the benefits discussed in this article.\