The Gift of Free Work

This carpenter's tribute to his late father-in-law describes the pleasure of helping someone else with a building project.

Thirty some years ago, when my wife and I bought our house, there were three lawyers at the closing. This was in addition to the seller, two real-estate agents, a bank manager, and us. All I could think was, “I’m paying for three lawyers.” At that very same moment, my father-in-law, Tony, was five miles away planting tomatoes in the backyard of what would soon become our home. A first-generation Italian American, he had his own ideas about how to take possession of a property.

The house was a 200-year-old Cape, tiny and run-down. It needed everything. But it sat on a nice piece of property, backed up to a land trust, with a river along one side. We thought it was worth saving. Run-down as it was, though, we still couldn’t have bought the place without Tony’s help. He loaned us $20,000 for a down payment.

Shortly after we moved in, we rented a dumpster and started gutting the house. Tony showed up that first weekend to help. He showed up again the weekend after that, and the one after that. He kept coming for the next 15 years.

I don’t remember asking for his help, or him offering it. We just fell into a rhythm. And even though he lived nearly an hour away, I’d hear his T100 pickup pulling into the gravel drive by 8:00 or 8:30 every weekend morning. His predictability meant that I couldn’t sleep in, or linger over a second cup of coffee, or blow off the day’s work for something more fun. If he was coming over, I had to be ready, with plans for the day, and with materials from the lumberyard.

Tony had recently taken early retirement from the telephone company. (This was back in the day when you said the telephone company because there was really only one.) Not one for sitting around, he immediately went to work as a handyman, happily doing the small jobs that most contractors refuse, and never charging enough.

I was a better carpenter than Tony, but he was a better jack-of-all-trades. Born into the Great Depression, he grew up in a world where, if something broke, you fixed it. He worked with tools his whole life. Tony could change the brakes on a car, get a chainsaw running again, or replace a breaker in your electrical panel.

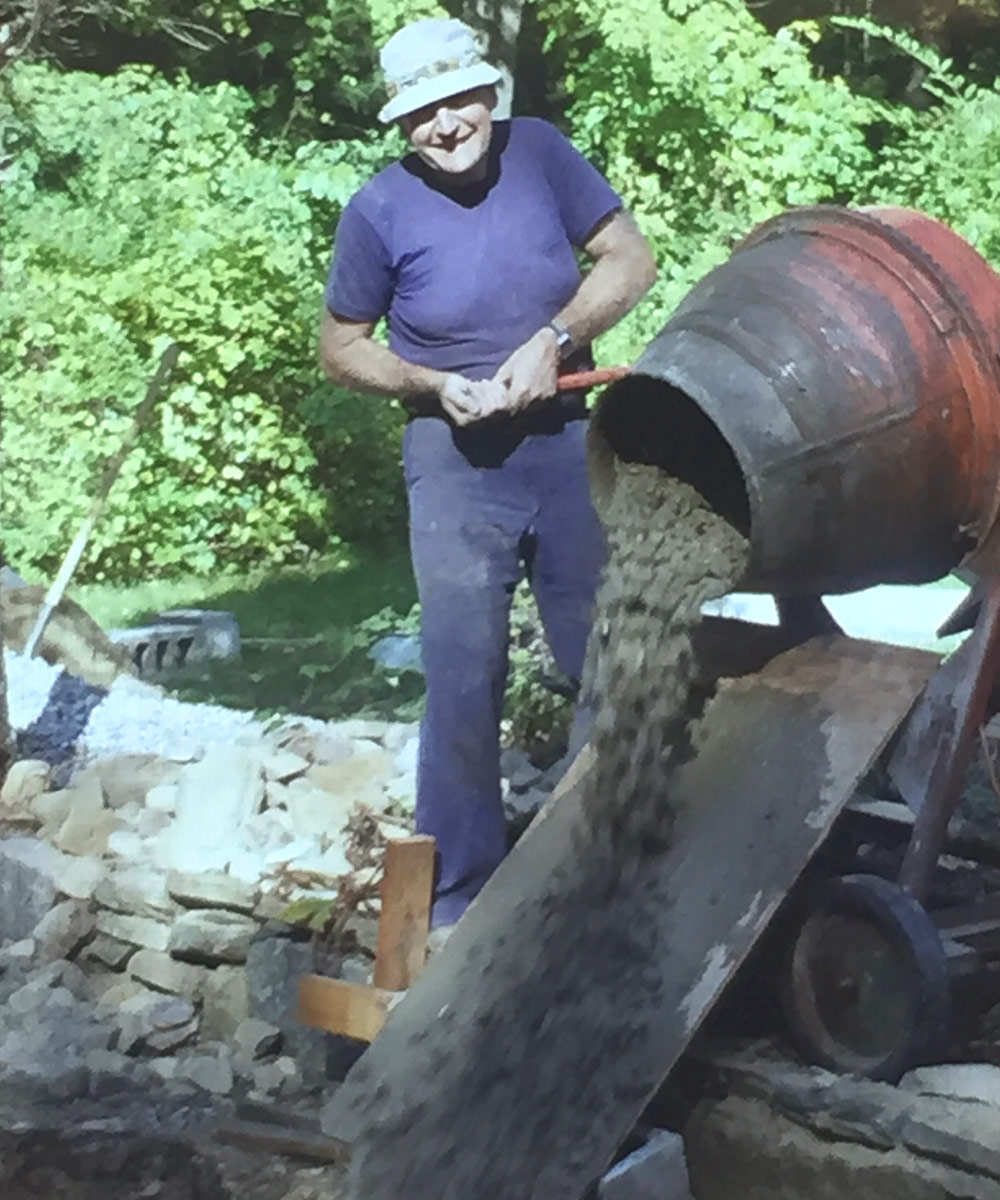

After gutting the house, we decided to move the only bathroom into an existing addition. It was a classic example of mission creep. The addition had a shed roof, and we thought it would look better with a gable. But when we demolished the roof, we realized the wall studs were staggered lengths, so we had to tear down the walls, too. Once that was done, we discovered how poorly built the floor was, which was how we learned that there was really no foundation. So in order to “reframe the roof,” we had to tear down the entire addition and dig 4 ft. into the ground. That’s when Tony brought his cement mixer over for the first time.

He’d bought it used for $100 and had poured countless patios, sidewalks, and deck piers. He’d loaned it out to friends and relatives (who never cleaned it properly). Tony and I mixed concrete for the new footings, and then mixed mortar for the concrete-block foundation. Afterwards, he said that if that the cement mixer lasted a few more years, he might get his money’s worth out of it.

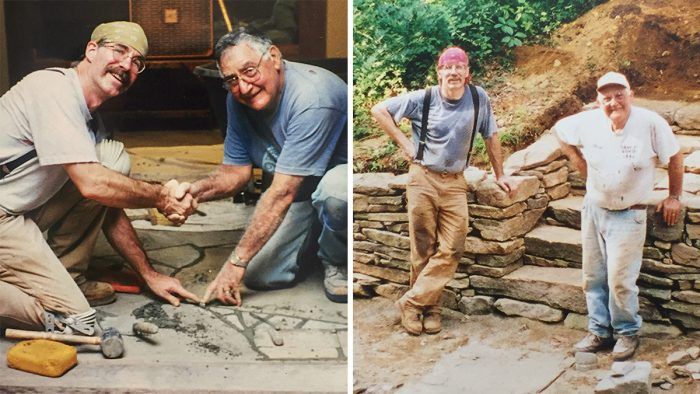

When we rebuilt that first addition, we did everything ourselves, which set the standard for the rest of our work on the place. Over the years, we built stone walls and laid brick patios. We installed hardwood floors, then sanded and finished them ourselves. We ran new wiring and new plumbing through the entire house. We set tile and built cabinets. We finished concrete, and we finished drywall. I’m not saying we were great at all of these things, but in an age when hiring a professional no longer guarantees a professional job, we were more than competent.

We didn’t really do “projects.” We just worked on the house, week after week, month after month, year after year. Yes, there were vacations, holidays, business trips, and other disruptions, but the routine was established early on. We worked on the house every weekend. It’s what we did. It’s what we talked about. When we saw the relatives at Thanksgiving or at the Fourth of July barbecue, they didn’t ask about Tony’s golf game, or if we’d been fishing. They asked, “How’s the house coming?”

If you haven’t done much building, then you can’t imagine the difference it makes to have a kindred soul by your side, especially for the hard, thankless tasks, such as the time we excavated the basement, hauling dirt out in 5-gal. buckets to gain a little more headroom before we poured a slab. The reason misery loves company is that company makes miserable jobs just a little less miserable. Tony did that for me year after year.

Tony was still helping me in his mid-60s, the age I am now. And as I struggle to put my socks on in the morning, I wish I had been a little more mindful of his aging body. Instead, I had him up on the roof with me in August. And I had him down on his knees beside me at 11:00 at night as we troweled the new basement slab. We spent one entire summer installing a bluestone floor in the living/ dining area of the big addition we built. The stones, set in a thick mortar bed, were irregular in shape and thickness, making the installation about as complicated as a floor can get. I have a photograph of us on our knees, shaking hands just after we set the last stone. Seeing our smiles, you’d think we’d just completed the transcontinental railroad.

During the whole time that he was helping me, I never heard Tony complain once about the weather, or about his back hurting. He never complained, but he did occasionally suggest that I might be better off dropping a lit match on the place and collecting the insurance. I knew we had reached a milestone when he stopped saying that.

I don’t know why Tony helped me for so many years. At first, I thought maybe he just wanted his daughter to have a nice house. Other times I suspected he was avoiding his wife or his own chores at home. We never talked about it, of course. He could go on at length about how the quality of paint had suffered since they took the lead out of it, but he wasn’t comfortable talking about anything personal. Telling his daughter that he loved her was hard, coming over to her house on Christmas Day and helping install a pedestal sink was easy.

By the time he got into his 70s, Tony began to slow down. He would spend more time watching than helping. Eventually he stopped coming up on weekends. There was less and less work. And I stopped calling to ask if he was coming over.

Over the years, I helped Tony work on his house a few times. We laid some hardwood flooring, rebuilt his deck, and installed a new front door, but I could never pay him back for all the time he gave me. So I decided to pay it forward whenever I could. I jump on any chance to help other people work on their places. Tony’s example taught me that having the skills and tools to do this kind of work carries with it certain obligations—to help, to teach, to empower, and yes, to share the misery.

Most important, Tony’s example taught me that if you love building, as he did and as I still do, it doesn’t get any better than working for free on someone else’s project. You get all the pleasure of the work, with minimal responsibility. You don’t have to plan anything. You just show up and work. You don’t even have to arrive early. Nobody’s going to yell at you. You don’t have to rush. You don’t have to bring your own lunch, or finish it in 30 minutes. Whoever you’re helping will just be grateful you’re there.

Tony passed away over the summer. He was 89 and lived a good life, so his death is no tragedy. But I miss him. I walk around my house and see his handiwork everywhere I turn. As I write this, my desk sits in front of the 18th-century double-hung windows that we restored. It took us months. We removed the old wavy glass and put it aside. We carefully scraped paint from the sash and delicate muntins by hand. Even I suspected we were crazy to save those windows until the very end of the process. Reglazing stiffened the wobbly sash, new paint freshened the look, weatherstripping and storm windows improved their performance. By the time we installed them, we both knew we’d done the right thing.

Looking out those windows, I’m reminded of what Tony used to say occasionally, when we were working on something particularly tedious and involved. He would look up at me and say, “Nobody is ever going to know what we did here.” But he and I knew. And we could remind each other. “Hey Tony, remember the time… we were finishing that slab after dark, using the truck headlights to see by?”

Now I think to myself, “Nobody is ever going to know what we did here.”

Kevin Ireton, editor at large, is a writer and remodeling contractor who divides his time between Connecticut and Arizona.

Photos: courtesy of the author

From Fine Homebuilding #312

RELATED STORIES