A History of U.S. Building Codes

Be it structural collapse, fire, or disease caused by water contamination or unsanitary waste disposal, the origin of building and health codes often can be traced to human tragedy.

Synopsis: Code expert Glenn Mathewson overviews the evolution of building codes in the U.S., detailing how various official organizations were formed to publish the first building standards and how this evolved into the International Code Council and the I-Codes we are familiar with today.

“Building codes are written in blood.” If you haven’t heard this before, it’s a reference to the main motivation that has generated the development of new building codes for centuries. While there are many motivations for the revision, creation, and maintenance of building codes, codes are mostly reactive in nature. Be it structural collapse, fire, or disease caused by water contamination or unsanitary waste disposal, the origin of building and health codes often can be traced to human tragedy.

At least as early as the 1600s, colonial cities such as Boston had codes called “building acts.” As you might expect, the primary purpose of these acts was to prevent the cities and towns from burning to the ground. The default regulation was to prohibit homes from being built and roofed with wood or other combustible materials. Clearly this was a top-down solution, as building human shelter from noncombustible materials such as brick, stone, and tile was not affordable for the large majority of the population, and it still isn’t today. Housing for the working class was a controversial topic in the United States even before the United States existed. But a building act is only as good as a government’s efforts to enforce it, and many of the jurisdictions at that time didn’t have a specific department or inspectors to do so. The insistence of governments to ban or limit wood carried on for centuries, as did the defiance of the people building homes and the fires that destroyed them.

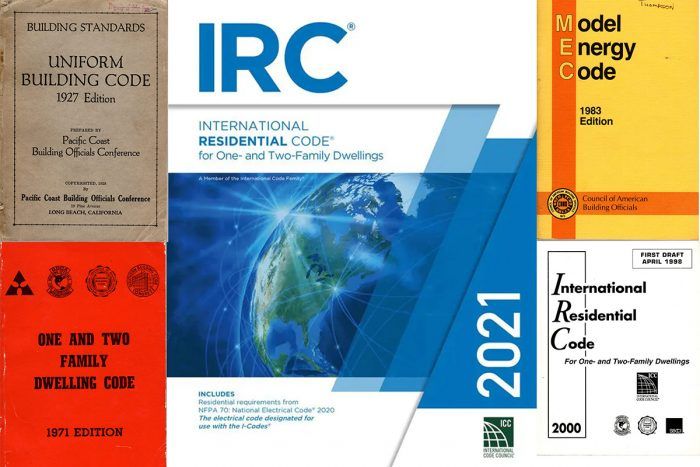

Built over timeGreat moments in the evolution of building codes 1600s – Cities such as Boston create building acts to prevent catastrophic fires 1850s – New York introduces plumbing design and plan review requirements 1866 – National Board of Fire Underwriters (NBFU) is created 1897 – NBFU publishes the NBFU No. 70, the first National Electrical Code (NEC) 1905 – NBFU publishes the Building Code Recommended by the National Board of Fire Underwriters |

A model code is born

In 1866, a group of insurance underwriters (the folks footing the bill to rebuild cities) formed the National Board of Fire Underwriters (NBFU). In the late 1800s the NBFU began investing heavily in reducing life- and property-threatening fires and their financial impact on the underwriters. They introduced the Building Code Recommended by the National Board of Fire Underwriters, the first “model” (suggested) code written to be a set of recommendations to governments. Free copies of this code and training support were provided to any jurisdictions that wanted to adopt it, an early example of an effective public-private benefit. Some cities continued to use their own unique building codes, but many jurisdictions eventually did adopt the NBFU’s Building Code or used an altered version of it.

Around this same time, health and sanitary codes were also becoming more common. While this doesn’t immediately sound related to construction, it very much is. What we would call plumbing codes today were provisions included in the early health codes. Water closets, privies, and cesspools were the topics of discussion. By the 1850s major cities such as New York had introduced significant plumbing requirements, including licensing and plan submission, all regulated by health code provisions.

While plumbing codes and building codes did improve public safety and health, they varied greatly across U.S. cities by the 1920s, and “specification codes” had become common. Instead of offering construction methods and building material options, specification codes specified exactly what to do. The federal government was receiving a lot of complaints about the increased cost of construction that resulted. In response, the Department of Commerce created the Building Code Committee to research prevailing U.S. codes and draft code recommendations for state and city governments. Over the next several decades, with the goals of reducing construction costs and increasing output, the federal government funded research subjects such as fire-reduction strategies, reliable plumbing standards, lumberload properties, and framing best practices. These reports became a resource for code development across the nation.

| 1921 – U.S. Department of Commerce creates the Building Code Committee

1927 – ICBO creates the first “model” building code published by a code-official organization 1930s – Building codes become less specific and more performance based 1940s – Lumber span tables, nailing schedules, and new prescriptive design codes are introduced 1942 – National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) is founded |

A push for consolidation

By 1940 three organizations of building officials had formed: the International Conference of Building Officials (ICBO) in the western part of the United States, the Southern Building Code Congress International (SBCCI), and Building Officials and Code Administrators International (BOCA) in the Northeast. By the 1950s all three organizations had developed their own model building codes to recommend to state and local governments. Building officials wanted code provisions that addressed more than just fire safety, the primary subject of the NBFU code. Structural provisions were included that would help guide designers toward building better structures and away from unnecessary overbuilding, but each region had unique concerns and experiences.

In the decades that followed, the building industry strove to unify codes and increase flexibility and options. “Performance codes” became more prevalent as a result. Performance codes describe the end results the codes seek rather than specifying exactly what construction methods to employ and which building materials to use. One example of this design flexibility is the requirement for a “fire-rated wall” that would resist fire for a period of time instead of prescribing a specific material or wall assembly to achieve that goal. Design professionals and engineers were given much more influence in deciding how homes would be built to meet the performance objectives required by the code.

After World War II and the housing boom that followed, the ICBO (the western group) began developing and publishing dwelling house pamphlets. These pamphlets were created alongside new editions of the ICBO’s Uniform Building Code (UBC) and provided “prescriptive design codes” in the form of span tables, nailing schedules, and other “recipes” for construction derived from the engineering and performance standards in the complete building code. The goal was to simplify house construction and reduce design costs. In later decades, the SBCCI (the southern group) would also produce a dwelling house pamphlet.

By the 1960s home building had become a national business, and architects, designers, and builders who worked on projects nationwide didn’t appreciate the confusion and inefficiency of having four different model codes across the country, three from building officials and one from insurance underwriters. Voicing their dissatisfaction resulted in the four separate organizations getting together to publish the 1971 One- and Two-Family Dwelling Code. This code also included building, plumbing, and mechanical provisions. And in 1972 the three noninsurance organizations combined to form the Council of American Building Officials (CABO). However, even after the formation of CABO, both the 1971 and the 1975 editions of the One- and Two-Family Dwelling Code were credited to all four individual organizations. By the 1979 edition, the National Board of Fire Underwriters, which by then had become the American Insurance Association (AIA), stepped out of the code publishing business completely, and CABO became the publisher.

The energy crisis drives updates

The formation of CABO was perfect timing for the federal government to again play a major role in influencing how homes would be constructed in the United States. With the energy crisis underway, the 1975 Energy Policy and Conservation Act enabled the Department of Energy to provide the necessary funding for CABO to develop a model energy code. By 1977 the Model Code for Energy Conservation was published. While some jurisdictions across the country did adopt it, this early energy code was not widely accepted. Energy provisions were not included in the CABO dwelling code directly, so a local government would have had to actively adopt the model energy code individually. CABO continued to publish its One- and Two-Family Dwelling Code every three years, and in the 1995 edition an agreement was made to include the electrical provisions from the National Fire Protection Association’s 1993 National Electrical Code (NEC).

| 1977 – The Model Energy Code is published by CABO with funding from the federal government

1979 – Third edition of One- and Two-Family Dwelling Code is published by CABO. AIA steps away from code publishing. 1994 – International Code Council (ICC) is formed 1995 – NEC provisions are added to CABO’s One- and Two- Family Dwelling Code 1995 – ICC publishes first “I-Code,” the International Plumbing Code (IPC) |

A path to widespread code adoption

Even with the ongoing effort to unify building standards, CABO’s dwelling and energy codes were not universally adopted, so in 1994 the International Code Council (ICC) was formed, publishing its first codes in 1995. In 2000, the first International Residential Code (IRC) was published and began to be adopted across the nation. From 1971 to 1998, individual jurisdictions could still choose between codes published by ICBO, SBCCI, and BOCA, or they could adopt CABO’s One- and Two-Family Dwelling Code. But by 2000 the IRC was for all intents and purposes the only code publication to choose from, and widespread adoption followed. In 2002, the three legacy organizations officially dissolved.

The federal government still does not have direct authority over building codes, but it does have influence in the form of providing or withholding federal grants to states that reach or fail to reach certain thresholds of energy code adoption. After the creation of the ICC and the publishing of the 2000 IRC, energy codes began to gain popularity, mostly due to changes in society and continued federal funding, but partly due to residential energy provisions being included directly in chapter 11 of the IRC. This made it easier and more practical for a government to adopt and enact energy conservation provisions, as otherwise it would have to intentionally remove them via amendment.

The completed versions of the I-Codes are documents essentially lobbied to state and local governments for adoption as law. Local jurisdictions have the authority to adopt the codes, reject specific provisions, or introduce more stringent versions of their own, depending on the authority granted by the state government above them.

Shortly after the publication of the first IRC, many began to believe that special interest groups were dominating the direction the code was taking. For example, the 2009 IRC included a controversial mandate for all new homes to include fire sprinkler systems. Many in the industry saw this as an expensive regulation not based on society’s concerns or needs but on the desires of specific interested parties in the industry. Over a decade later, most governments still reject this recommended mandate.

An ever-evolving process

In 2015, the ICC implemented an online process for code development and voting. This was to ensure that a broader voice of building and fire professionals could be heard and a more balanced final outcome would result. The ICC process for developing the next edition of its codes is open to everyone and is completely transparent. Nothing is sacred, in that anyone can suggest a new provision or ask for a change to an existing code. And all proposals can be modified by others before being voted on. The final vote is made by ICC government members (the jurisdiction as a whole), which includes state and city government employees working in public health, safety, and general welfare.

A more recent change in the code development process is meant, in part, to address another controversy. Each ICC government member is allotted a certain number of voting members (4 to 12) based on the population of the jurisdiction, but not every jurisdiction fills those positions or maximizes its number of final, online votes. During the development of the 2021 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC), some proposals requested an increase in minimum R-value requirements but were rejected throughout the entire in-person process, including two hearings. However, an organization primarily interested in building energy efficiency made a concerted effort to assist like-minded jurisdictions in filling all their available voting seats, and in a surprise to many, the proposals were approved in the final online vote. These changes went beyond what many felt were reasonable and were presumably a result of the efforts to maximize affirmative votes. Likely related, the ICC moved the development of the 2024 IECC to a completely different process, using ANSI-standards development protocols that rely on committees to make the final approval. Additional changes were recently made to the process of developing all the 2027 I-Codes, starting in 2024. Like fire sprinklers, many jurisdictions are rejecting the new energy code and adopting the 2018 code instead. Unlike with sprinklers, however, the federal government is promoting and funding energy code updates in states, so many others are moving to the more robust edition.

The history and major milestones of the U.S. building code system are complex and profound, and this is just an overview of the entire story. The construction industry is also complex and is constantly changing with new materials, economics, societal expectations, and human creativity. Building codes are intended to change alongside these variables. However, as stated in the preface of the original 1927 Uniform Building Code, “The code is not, and never will be, perfect.”

Glenn Mathewson is a consultant and educator with BuildingCodeCollege.com.

From Fine Homebuilding #317

RELATED STORIES