How to Reuse Salvaged Wood

A historical-home renovation gives lessons into the process of reclaiming lumber, from careful demolition to remilling and refinishing.

Synopsis: Using a recent gut-and-expansion project as an example, builder Jim Wolffer explains how his company reuses salvaged wood. He covers how to assess whether lumber is worth saving or not, the importance of developing a reuse plan that includes the homeowner, and setting up an area for de-nailing, remilling, and refinishing the salvaged lumber.

We work in an area that has a lot of really old houses, some dating back to the 1600s. Our latest project, designed by architect Steve Baczek, was a complete gut and expansion of an 1870s New England farmhouse. All too often projects such as this result in dumpster loads of material being sent off to the landfill instead of being repurposed strategically in the renovation. With our company’s reputation for thoughtful use of salvaged material, these homeowners wanted us to save as much original building material as possible during demolition. We were then asked to incorporate some of that material into the renovation. This project is a perfect illustration of how that strategy can work successfully.

We work in an area that has a lot of really old houses, some dating back to the 1600s. Our latest project, designed by architect Steve Baczek, was a complete gut and expansion of an 1870s New England farmhouse. All too often projects such as this result in dumpster loads of material being sent off to the landfill instead of being repurposed strategically in the renovation. With our company’s reputation for thoughtful use of salvaged material, these homeowners wanted us to save as much original building material as possible during demolition. We were then asked to incorporate some of that material into the renovation. This project is a perfect illustration of how that strategy can work successfully.

Start with careful demolition

Our process begins by assessing what material can be saved from demolition. In this case, the existing farmhouse had gone through many renovations over the years, so there wasn’t much in the way of period moldings or detailed millwork to save. Instead, we opted to go after material such as the original flooring and structural lumber and timber. (If you’re reusing older painted material, take appropriate lead-safe precautions.)

If your renovation plans require you to remove interior wall partitions or exterior walls, plan to save the framing lumber. Remove every board by hand, and keep each one as free of damage and as long as possible. This approach requires more patience and takes more time than the sledgehammer/demo-saw method, but the result is more rewarding. Beautiful old wood gleaned from a careful demolition can then be put back into the house instead of the dumpster.

A big part of the demolition strategy is planning ahead for a place to put the wood as you take it out of the house. Ideally that place should be close by and should minimize the wood’s exposure to the weather. For the project pictured here, the home’s large wraparound porch provided a convenient place to pile the demolition wood. An alternative is to store the wood temporarily on pallets and cover it with a heavy-duty tarp.

Discover what you’ve got

As demolition progresses, you need a way to figure out what lumber is worth saving and what isn’t. Back 150 years ago, construction lumber all came from trees that themselves were centuries old. If you’re reclaiming wood from a house that was built in the 19th century or earlier, expect the wood grain—including that of the framing material—to be extremely tight.

A good way to assess the quality of the wood is by running some samples through a planer. Exposing the grain of salvaged wood can be really exciting. The test pieces we planed revealed tight, mostly clear grain (top photos, facing page).

As the demolition progresses, keep an eye out for hidden caches of wood. In a room that had served as the kitchen in the original house, we found beautiful vertical-grain heart-pine floor boards under more-recently installed flooring. Heart pine—known for its extreme durability—was the flooring of choice for an 1870s hardworking kitchen, and those clear, tight-grained boards were still in wonderful shape.

In addition to the flooring and framing, save any old doors and windows that are in decent condition. These can be incorporated creatively into your renovation. But be aware that much of the wood used for plaster lath and strapping is of inferior grades and probably isn’t worth saving.

As you examine the wood exposed in the planing, develop a system for separating boards that will make the best “smooth finish” lumber from those that will work better for a rougher, more rustic surface.

Develop a reuse plan

A common mistake is reusing salvaged wood randomly in a renovation, such as for a single window stool. Avoid having your finished project look like you just slapped a bunch of old wood around for the heck of it. At the project planning stage, identify areas where you might be able to incorporate reclaimed wood in a manner that is appropriate to the style of the renovation. Get the homeowners involved as early as possible to discuss where to use the materials.

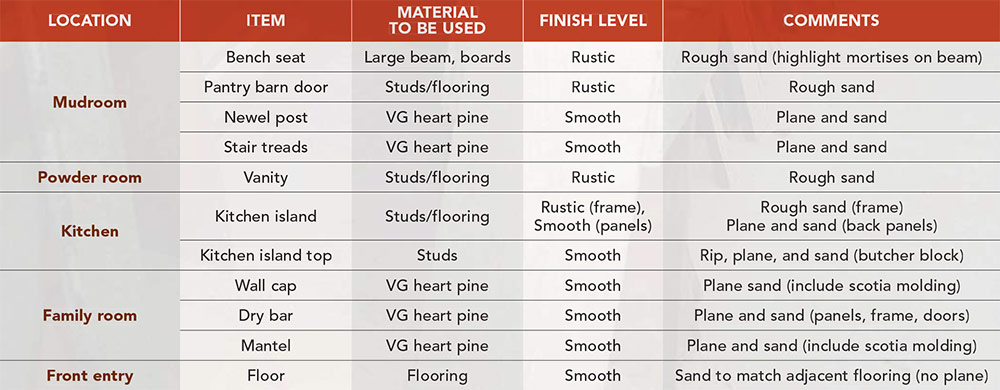

As the demolition on our project progressed and we moved closer to working on the interior, we met with the homeowners to outline which projects would best lend themselves to repurposing the reclaimed materials. We came up with an initial list of ideas for using the reclaimed lumber as major architectural accents in the various rooms being renovated. Besides identifying the material to be used, we also discussed the finish level we wanted for each item. We put all the information into a spreadsheet (reproduced in the chart, below), which is a great way to keep everything organized.

Start with de-nailing

It’s always a good idea to have a specific room or nearby building for processing the salvaged wood. For this project, we set up that area in the new garage. Regardless of how you ultimately want to use the wood, the first step always is to remove all the nails. Initially we thought it would be more efficient to de-nail all the wood before we started building things, but de-nailing and cleaning up the boards is such an arduous task that we opted to de-nail as the wood was needed for each element to keep ourselves from getting bogged down in a tedious job.

Use time and space efficiently

Always choose which project to build first based on the role it plays in the rest of the renovation. For example, we had to build and install the powder-room vanity before the plumbing could be finished. When the vanity was finished, we also had to template and order the countertop, which had a substantial lead time.

For the most efficient use of time and shop space, try to group together elements that use the same material, and then process the salvaged wood and fabricate the elements at the same time. We made three different elements from the original heart-pine flooring, planed down to a smooth finish: a mantel and fireplace surround, treads and a newel post for a new stairway, and a decorative cap for a separation wall (see photos, below).

Different Elements, Same Material: We planed down the original heart-pine flooring to a smooth finish to fabricate a decorative cap for a separation wall, a mantel and fireplace surround, and treads and a newel post for a stairwell. A few coats of water-based polyurethane protect the remilled wood.

For the larger interior projects that require a lot of milling and more traditional construction techniques, it often makes sense to move your operations to a bigger shop. In our case, we rough-cut material for the vanity doors, the barn door, the kitchen island, and the dry-bar cabinet on-site, then labeled the pieces and took them to the shop, where we could take advantage of the shop tools and a little more elbow room.

Salvaged materials are milled to a Smooth Finish in a sequence similar to that of rough lumber purchased at a lumberyard. But before running boards over a jointer, scrape the edges to remove any hardened varnish and debris. The jointer creates a straight edge and a flat surface to facilitate planing boards to thickness. The newly jointed edges allow you to glue boards together for wider panels and to fabricate moldings that match the rest of the finished elements.

Where a Rustic Finish is desired, light planing or just sanding the surface of the material maintains much of the weathered color of the wood. This treatment can also leave saw marks from when the wood was originally milled and indexing marks from the original carpenters. For the framework of this powder-room vanity, the original stud tenons act as feet. As with a smooth finish, a few coats of water-based polyurethane seal the wood; they also preserve the rustic weathered texture.

From Fine Homebuilding #320

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.

RELATED STORIES

View Comments

100% denailing can be harder than it looks and can lead to damaged planer blades. Replacing them is both expensive and time consuming, so I keep a cheap Harbor Freight metal detector next to my planer. Saving even one set of blades is more than enough to pay itself off.

Lots of great inside information in this piece. I've done a bunch of restoration work over the years and it's never quick & easy, but worth the time & effort for the end result.

I did a 3-part video with FHB in 2009 about dismantling, moving, restoring and reusing original salvaged materials in an 18th century timber frame Connecticut house that proves the point.