Using AAC Blocks and Local Materials

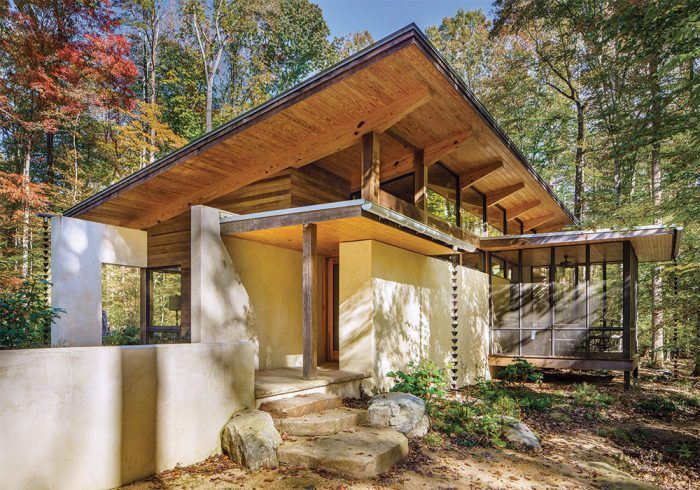

Considerate material choices, the use of AAC blocks, and careful siting create a home that complements the owners' love of craft and folklore.

Synopsis: Architect Tina Govan’s clients had strong feelings about materials. Locally sourced pine beams were used instead of glulams for the roof framing, and local sources were also found for almost all the solid wood used in the house. AAC blocks provide structure, thermal mass, and insulation. At the same time, they can be cut and sculpted to accommodate window and door openings as well as electrical conduit. These and other materials were used to create a house with two wings, one private and one public, that is integrated respectfully into its woodland setting.

When Amy and Glenn first approached me about designing their home in Chapel Hill, N.C., we aligned immediately along the intention of creating a strongly place-based home. We wanted to create a retreat that put them in daily connection and appreciation of this specific piece of the North Carolina Piedmont, a wooded hill wrapped on three sides by Morgan Creek. From the materials to the siting and integration of building and landscape, this would be a home that grew from here. Amy and Glenn were dedicated to uncovering the qualities unique to this site.

They shared a deep passion for the locally handmade. Glenn, a folklorist at UNC-Chapel Hill, had gathered a wide range of culturally rich music, folk art, pottery, paintings, and fish traps, each with a story behind them. Amy, as a family therapist, brought an intuitive sense of how spaces support well-being, as well as a keen eye for design and an amazing collection of traditional textiles, objects, and furniture that she hoped their new home would hold and celebrate.

Similar to the objects they’d collected, they hoped this house would reflect its careful making. Every client is unique, of course, but I knew this was not going to be a typical project. Amy and Glenn brought a particularly strong set of values with them. They were not interested in creating another slick modern home of crisp, white, drywall interiors outfitted with manufactured materials and fixtures. They wanted the home to reflect their love of the imperfect, and to include crafted objects and materials that reflect their age and the process of their making.

Prioritizing “real” materials

Rarely had clients come to me with such strong feelings about materials, their touch and feel, and the story of their origins, along with a desire to work with a team of caring local craftspeople who would artfully assemble them. Glenn wanted to minimize factory-made products, such as plywood, and envisioned a house where even the doors and door knobs would bear the human touch.

We ultimately decided on a palette of local wood, natural stone, and aerated, autoclaved concrete (AAC) block walls. Bob Wuopio of Formdb, our maestro builder, describes this project in relation to others he’s built as “old school,” with solid pine beams, 2x decking, 12-in.-thick no-cavity masonry walls, 6-in.-thick stone patios, and solid wood doors and cabinetry.

He said, “This use of real material gives this house a feeling of authenticity. The use of sheet goods is highlighted in most modern homes while it is nearly forbidden here. It is more difficult to work with solid material than sheet goods and cavity walls, but the celebration of the solid is evident throughout Amy and Glenn’s home.”

In addition to sourcing local pine logs for roof beams, we were able to find local sources for nearly all of the solid wood used in the house. The flooring, for example, is reclaimed 10-in.-wide heart pine, milled from beams from an old cotton mill; the siding is thermally modified local poplar; and the ceiling and trim is all local southern yellow pine. Even the floor outlet covers and registers were not manufactured but handcrafted out of the heart pine, with care taken to match the grain of the surrounding floor.

Plywood could not be avoided altogether, of course. Structurally, we needed its shear capacity and diaphragm action to transfer in-plane lateral loads, and so used it for wall, roof, and floor sheathing, as well as for the cabinet boxes, but it is always hidden. Amy and Glenn responded to things haptically and were purists when it came to the finishes they could see and touch. One example is the interior doors. Visually and tactilely, they are solid, but they are built using a torsion plywood box core. Solid 3 ⁄ 4-in. heart pine, salvaged from Amy and Glenn’s 1870 farmhouse in Creedmoor, was applied to all sides of this box core, which ensured that it would remain flat. The glass doors, which are a frame rather than a solid plane, were of greatest concern for twisting and cupping. They ended up being 2-3 ⁄ 8 in. thick with all corners grain-matched and mitered. All are perfectly flat and they are one of Glenn’s favorite features of the house.

Using AAC blocks

The decision to use AAC blocks was inspired by images Amy presented of a friend’s stone house in Spain that she loved. She wanted that same feeling of solidity, strength, connectedness to the ground, and timelessness. Other than rammed earth or adobe, AAC, as a solid homogeneous block, is in my view the closest alternative we have to building with stone today.

The AAC walls anchor the building to the site, creating a kind of “ruin” definition of the building, what would be left if all the other parts had blown away. Plastered identically on the interior as the exterior, they ignore distinctions between inside and outside, extending out into the landscape as garden walls, defining paths and creating privacy screens. Clearly distinct from the wood frame of the house, these thick, plastered walls grow up out of the ground, supporting shed roofs that lift up and out to the woods and sky on either side. They provide a strong foundation upon which the wood rests and infills between. In this way, the structure is very “legible.” In comparison to a structure that’s built with stud walls and then camouflaged with an applied finish, here the structure is the finish. This kind of authenticity resonated with Amy and Glenn.

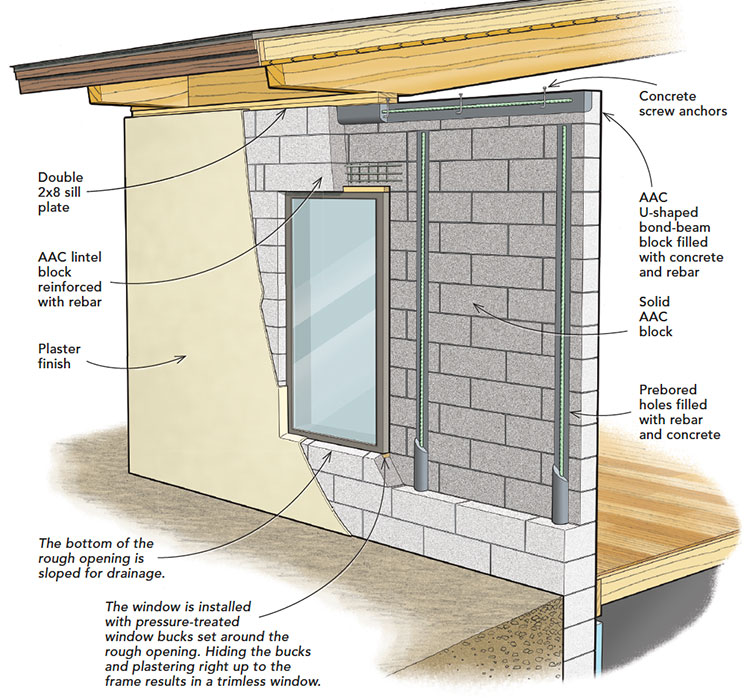

AAC is simultaneously strong yet soft, plastered inside and out in a way that makes it look and feel like adobe. Sculptors often use it because it can be cut and shaped using simple wood saws and sandpaper. Window openings and joints can be gently sculpted in a way that is not possible with traditional concrete block. The aeration of the concrete renders it friendly and workable. This allowed us to carve custom wall niches for art, furniture, and Glenn’s walking stick collection. This workability also allows you to easily route out channels for conduit—which needs to be used over wires and plumbing when working with AAC—and plaster them over.

Plaster walls with aerated concrete

Aerated, autoclaved concrete (AAC) walls are typically made up of four different block types. Typical solid blocks are 24 in. long and either 8 in. or 12 in. thick. They do come in a variety of heights, though the standard is 8 in. tall. A U-shaped block filled with concrete and rebar forms a continuous bond at the top of each wall. Every 4 ft., columns of concrete reinforced with rebar are poured into a third type of block with prebored vertical holes, tying the top bond beam to the CMU foundation below. The solid AAC block is then infilled within this framework. You can choose to drill these cores yourself, instead of selecting these specific blocks. The last type of block is a lintel block, which is embedded with reinforcing rebar and comes in different sizes depending on the opening.

The 1 ⁄ 16-in.-thick joints are connected with thin-bed mortar that sticks easily to the light and porous blocks, creating walls that are almost completely homogeneous. The result is a quiet, meditative space. One of the aspects I love most about AAC, though, is the way it catches light and shadow. In this wooded setting, the walls, indoors and out, are continually animated by the dancing light and shadow of the surrounding forest.

AAC is made from a mixture of sand, cement, lime, gypsum, water, and fly ash, a waste product. A small amount of an expanding agent, such as hydrogen peroxide or aluminum powder, gives AAC blocks their porous, foam-like texture, making them 80% void, lightweight, easy to handle, and excellent insulation. Environmentally, AAC is a truly green material, recyclable and supremely airtight, simultaneously providing structure, thermal mass, and insulation. Chemically inert, it is resistant to fire, mold, and termites and gives off no harmful gases. An advantage is that AAC dries to all sides. It doesn’t have interconnected porosity, so capillary action breaks down quickly and moisture cannot continue “pulling” very deep into the material. Only the material near the surface directly in contact with the water is affected, but it is protected by a plaster finish that is both water-repellent and breathable, making it easy for moisture to dry. We used 12-in.-thick walls on this project, and due to reduced air infiltration and the thermal mass effect, they outperform stud walls rated at R-30.

Though used extensively abroad, AAC has been slow to take off here in the U.S. One reason may be its availability, which can vary depending on location (our source was AERCON, based in Florida). Another may be builders’ reluctance to try unfamiliar materials. The learning curve is small, however, and most masons have no problem with it. Builders I’ve worked with have been surprised at how easy it is to build with. We were lucky to re-enlist Kelly Finch, an old-time AAC builder from Mt. Olive, N.C., who had built a beautiful AAC farmhouse for me 15 years earlier (See “Modern Masonry Farmhouse,” FHB #235). He loves the material and is a valuable resource for anyone interested in AAC. Impressively, for both projects he set up camp on-site, living and working in place until his job was complete.

Set up for indoor/outdoor living

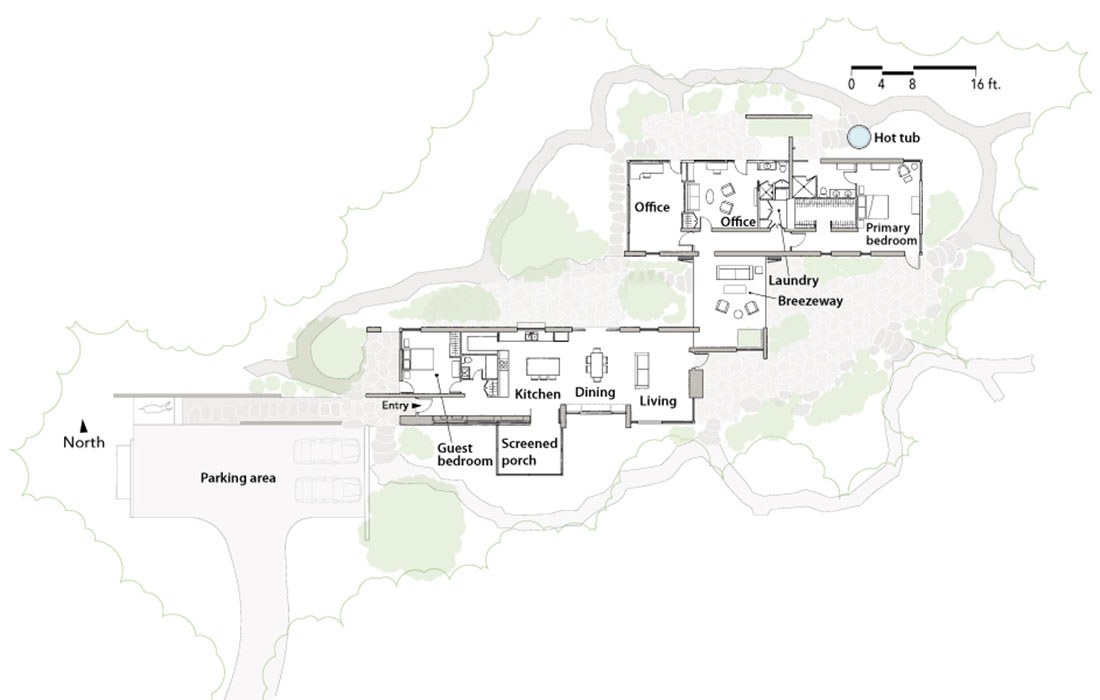

The house is designed as two simple wings, one private and one public, which slide past each other in the woods, carefully slipped between existing trees. In between, the landscape continues through. A flexible indoor/outdoor breezeway gently holds the two structures together, opening or closing depending on the weather.

Within this simple design, options abound. Flexible openings to the outside allow the home to expand and contract with the seasons. A screened porch and multiple patios on-grade on all sides allow interior spaces to spill outside seamlessly. The owners can live inside, outside, or anywhere along a spectrum of places between the two. Living, dining, resting, and even bathing happen as easily outside as inside.

The same craft and care applied to the indoor spaces were applied outside as well. Only native plants were used in the landscaping and 6-in.-thick local stone slabs were meticulously fit together like a jigsaw puzzle for the patios and walkways. Amy and Glenn accepted that this kind of work could not be done quickly or by just anyone. They prioritized careful craftsmanship and materials over speediness and the end result reflects this.

The value of a good team

All great homes—in fact, all great works—are born out of people caring deeply about something, and that was certainly true of this project. In addition to caring clients, we had an amazing team of co-creators, builders, craftsmen, masons, landscapers, furniture makers, and more who cared deeply about what they were doing. This project taught me the value not only of assembling such a dedicated team but of inviting all members to contribute in a way that allows their individual skills to shine (architects, take note). Nothing is more rewarding than building something amazing together with others.

Nestled in the landscape

We conceived the overall design as “a built passage through the landscape.” A public hiking trail along nearby Morgan Creek is integrated into the property, with vegetative screening to protect Amy and Glenn’s privacy. The home itself defines a path and a continuity of landscape, from the woods beyond to the car parking, through the breezeway, and down to the creek below. It’s as if the building were something you discovered while taking a walk through the woods.

SPECS

Bedrooms: 2 (with 2 offices)

Bathrooms: 3

Size: 2680 sq. ft.

Completed: 2022

Location: Chapel Hill, N.C.

Architect: Tina Govan, tinagovan.com

Builder: Bob Wuopio, Formdb, formdesignbuild.org

Prior to construction, we meticulously located and identified all trees within a 175-ft. radius of the potential building area and carefully sited the home to minimize their destruction. The trees are central to the design, defining indoor and outdoor spaces equally with the building. Views through the house intentionally frame trees beyond, bringing them close so they become “co-inhabitants” of the house. Amy and Glenn each have a home office that is defined as much by the surrounding forest as by the building itself. It is as if they step out among the tree trunks to work.

As lovers of the handmade, of indigenous art and craft, and of native landscapes, Amy and Glenn created a home that reflects just this. It brings them close, allowing them to live in intimate daily connection to what they love. A quiet retreat carefully crafted among the trees, it is inhabited not only by Amy and Glenn, but by their treasured folk art collections and the ever-changing light, shadow, and views of the natural world in which it sits.

–Tina Govan (tinagovan.com) is an architect in Raleigh, N.C.

Photos by Melville Nathanson © Kristine Dittmer Photographers, except where noted.

This article originally appeared as “A Sense of Place” in Fine Homebuilding #320

RELATED STORIES

- Utilizing Your Whole Lot for Better Living

- Vernacular Architecture and Sustainable Design

- Webinar: Designing Outdoor Spaces

View Article PDF |

View Comments

What a stunningly beautiful project in eveery aspect.

I love the use of AAC blocks, the plastering gives the final finish the look of adobe, I always love to learn of new materials and methods.

Congrats on a masterpiece,

Gordon

One question... What was the final cost per sq ft??

Thanks!

I love this project and am currently working on a project that is also about prioritizing real materials.

As I will be applying an exterior coating, I am curious about the exterior “plaster” coating. There was no detail in the article. Can you provide more detail on the composition of this material? Is it a name brand or was it mixed on site?