Budgeting Is Helpful. Estimating, Not So Much.

Learn how discussing a budget with clients and narrowing it before reaching a contract can lead to design decisions that won't change the project's scope.

In my role as production manager at TDS Custom Construction I am responsible for producing several different budgets for each project as it moves through our process, beginning with an initial suggested construction budget and ending with a fixed-price contract. From a client’s first interaction with us through the entire process of schematic design and design development, my construction budgeting work allows the client to become an informed part of the project team. You may have noticed that nowhere in that brief overview of our process did I refer to my work as “estimating” or to my deliverable to the client as an “estimate.” This is by design.

Our interactions with clients on the office side help set expectations for the entire client-contractor relationship, and clearly explaining the costs involved in a project empowers the project team, of which the client is a part, to make well-informed decisions. I believe that the first step in creating an environment where the project team can speak intelligently and professionally about project cost is to reconsider the words that we use to discuss it.

Take Estimates Out of the Equation

Consider the connotations of the words estimate, budget, and price more so than their dictionary definitions. An estimate is provided to a prospective consumer of a service by the seller based on their domain expertise—e.g., “Chuck is going to give me an estimate for my addition.” In the mind of the consumer the estimate is owned by the expert who created it and they have little influence on it. After all, the estimating process happens out of their view and with minimal input.

The estimated cost may even be expressed as a range to shield the seller of the service from the risks they see in performing the work (“Chuck told me that the addition could cost $100,000 to $150,000”). This estimated range and the uncertainty it creates in the mind of the consumer can result in distrust of the numbers by the purchaser and lead to a situation where the consumer feels empowered to ask for a discount by suggesting that the estimator sharpen their pencil. I can empathize with Chuck, and I freely admit that I have failed at the sales process many times by not understanding how my language was setting me up to fail.

The idea of a budget is something that nearly all consumers understand. You may have personal budgets for vacations, household expenses, gifts, and other major purchases. These budgets are made through a series of educated decisions that culminate in a sum cost based on the amount of money that you are willing to dedicate to each line item on the budget. When you are budgeting you are maximally in control of how you will allocate your financial resources even when you are not an expert consumer. When planning a European vacation, you may choose to book flights, hotels, ground transport, dining, and attractions on your own. Or you might hire an expert to help you with all or part of the planning so that you can make the best decisions possible. Having a strategy for producing a clear, concise budget for a complex purchase is what makes an expert valuable.

Narrowing the Cone of Uncertainty

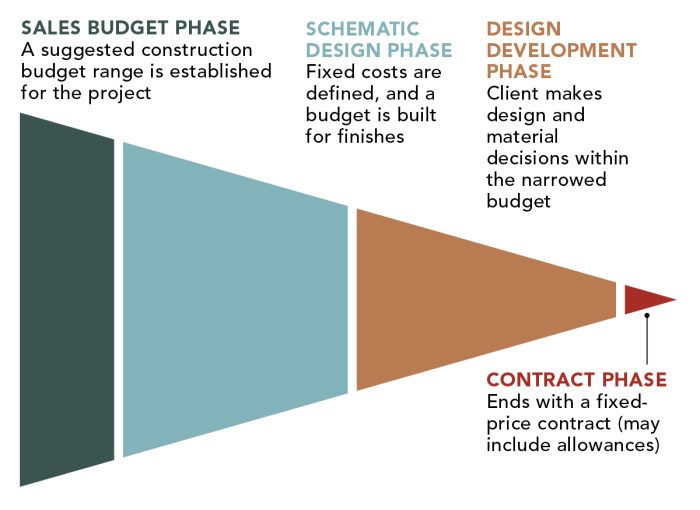

With a loosely defined project in hand, we provide a suggested construction budget (SCB) at low or no cost to the client. The signed SCB is then narrowed through the schematic design and design development phases into a fixed contract. While the project moves through a series of budgets, at no point in the process do we provide an “estimate.”

The foundation for my budget-building strategy is the cone of uncertainty. You may be familiar with the cone of uncertainty from weather-reporting maps seen during hurricane season that attempt to predict where a storm will make landfall. The point of the cone is the current location of the storm, while the open end of the cone represents the range of locations where the storm is expected to make landfall based on the best information available to the weather service.

My view of a construction project starts with the open end of the cone, which represents the cost range for a client’s project based solely on the information available. In my work this can be as little as, “I would like new kitchen cabinets, how much will that cost?” Other clients might show up to our first meeting with sketches, floor plans, and an image file full of desired finishes. The act of designing and budgeting construction projects rarely follows a point-A to point-B path.

Even clients who believe that they know exactly what they want will pick up new ideas and expand on current ones after working with architects and designers. Budgeting is key to helping clients and designers know which ideas are worth expanding on and which ideas are out of reach. As I work with the client and the design team the scope of the project comes into focus and the cone of uncertainty narrows, at which point our work becomes specific enough to produce a fixed-price contract.

The Suggested Construction Budget

The first budget that I produce for a client is a “suggested construction budget,” or SCB. This budget is intended to give the client a framework for making decisions about the scope of the project while working with the design team. This budget is tailor-made for the “I would like so-and-so; how much will that cost?” client. The SCB gives a simplified overview of the costs associated with the client’s project based on my previous experience with the project type and the information that I get from the client.

Importantly, this budget is meant to prequalify the client financially and create the foundation for future decision-making, not to answer the final question of how much the project will cost. For the majority of our projects we do not charge for the SCB. We consider this work part of our sales process and worth the effort to qualify the client before committing to the time-consuming work of design.

Start With Design

In my experience, design work is the only reliable way to narrow of the cone of uncertainty, and the first step is to take the client’s idea and begin to flesh it out through schematic design. The “schematic design budget” will begin to define the fixed costs associated with a project and the remaining budget for the client’s preferred finishes. For a kitchen addition, the fixed costs could include the structure and foundation and possible mechanical upgrades required for the project. The defining of this scope allows me to narrow the budget range and give the client a clearer picture of the total project budget leftover for their choice of finishes.

This schematic design budget is a more clear look at the price of the project, which sets clients up for the decisions required to move the project into the design development phase. The ideal outcome of this phase is a permit-ready set of drawings and specs, and a project that is ready for construction. If the client’s decision-making process does not fully narrow the cone of uncertainty at this phase, we work together to quantify the options under consideration into cost ranges specifically for that scope of work. This allows us to create a fixed-price-plus-allowances contract to sell the project and begin procuring items with long lead times.

Thoughtful Budgeting Leads to Optimal Results

As building costs continue to rise, the decision-making ability of our clients and their willingness to pay for professionally designed and built projects becomes equally as important as our ability as an industry to accurately price our work. Building these budgets and a system for delivering them is a time-consuming piece of process development, but when done thoughtfully as part of a larger sales and design process, a budget becomes the bridge that allows all members of the project team to work together making decisions that move the project along on its path from idea to built reality.

— Ian Schwandt; contributing editor and production manager at TDS Custom Construction.

From Fine Homebuilding #323

RELATED STORIES