Bracing for the Storm

Insurance industry research shows that stout roofs, strong windows, and metal connectors can help protect houses from high wind, hail, and hurricanes.

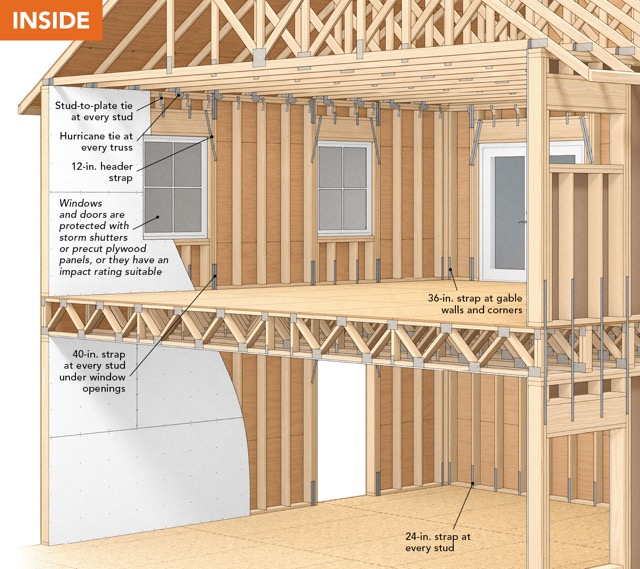

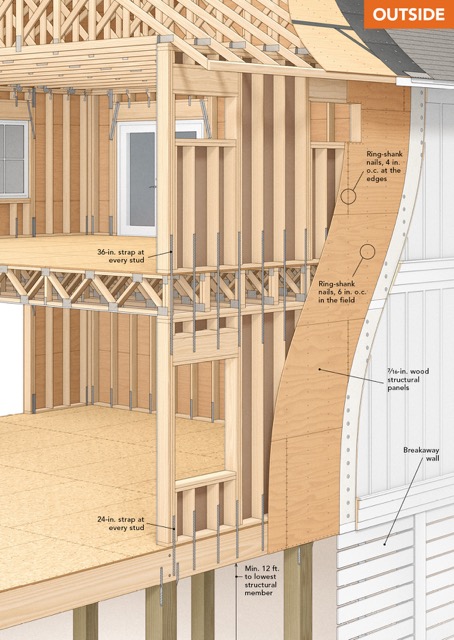

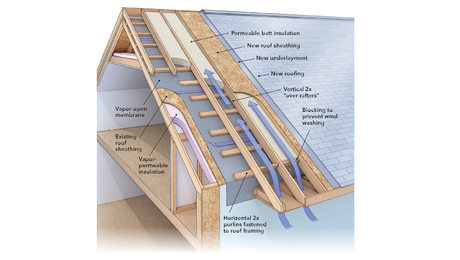

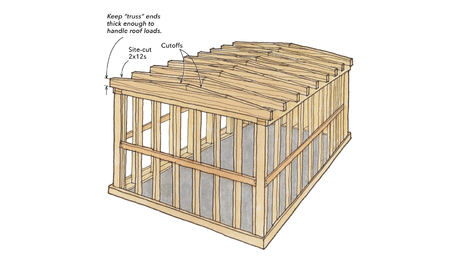

On a visit to the Gulf Coast of Alabama, senior editor Patrick McCombe met with builder Ben Murphy to discuss the Fortified Home standard that offers increased resilience for homes against natural disasters. Ben’s Fortified Roofs have weathered storms that leveled other homes in the area. In this article, detailed drawings show hurricane-proof construction methods in the reinforced roof, floor, and wall assemblies of a Fortified Roof and a Fortified Silver or Gold home.

Preparing for Hurricanes

My whole career, I’ve thought about and seen hurricane damage up close. My first-ever work trip was in 1996 to Miami, Fl., to see the rebuilding efforts after Hurricane Andrew. Two years after the storm, the recovery was still in its earliest stages, and I can still remember what seemed like endless blocks of devastation. Ten years later, I flew to New Orleans to witness the same recovery efforts one year after Hurricane Katrina. In reality, we saw very little rebuilding—only trash haulers and residents dealing with the moldy mess. Full reconstruction would take several more years, and some parts of New Orleans and the Gulf Coast would never look like they did pre-Katrina.

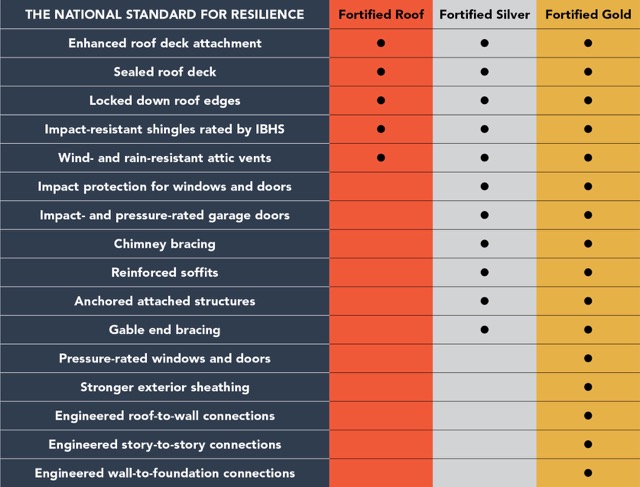

3 Basic Types of Fortified

Fortified standards include three designation levels for both new homes and retrofits. Each level builds on the last and includes additional improvements for increased resilience against natural disasters.

In July of last year I was back on the Gulf Coast, but this time it wasn’t to see hurricane damage. I was meeting with Ben Murphy, a roofing contractor and home builder in Foley, Ala. Since I was last on the Gulf Coast, Alabama had incentivized the Fortified building standard in an effort to reduce damage from hail, high winds, and flooding caused by hurricanes and intense storms.

The Fortified Home standard is a program of the Institute for Business and Home Safety (IBHS), a nonprofit researcher working on behalf of the United States insurance industry. The material and assembly testing at the IBHS research lab in South Carolina and its investigations following major storms have led to standards meant to make homes more resilient during severe weather. The jaw-dropping research facility can simulate hurricane-force wind and rain, hail, and flying projectiles.

Strong Storms—Big Claims

Building houses to better protect occupants is becoming a necessity as major storms happen more often. Since 2015, there have been 50 storms with $1 billion or more in damages; every year in the last decade, there has been between $8 and $14 billion in hail damage. Given the huge dollar amounts involved, IBHS developed the Fortified standard—a three-tier program to help roofs, houses, and commercial buildings survive severe weather events including hurricanes, hail and tornadoes (see “Three Basic Types of Fortified” chart above).

I was curious to see what makes a Fortified Home, and when I reached out, IBHS put Ben and I in touch. Ben has been a Fortified roofer for more than a decade. He agreed to show me a new town-home development he was building in Orange Beach, Ala., that is engineered and built to achieve a Fortified Gold designation.

While we walked around his project, he told me about Hurricane Sally, a 2020 a storm that made landfall near Gulf Shores, Ala., 10 miles south of his company headquarters. Winds were 110 miles per hour when the storm came ashore, and it rained 20 in. in the first 24 hours and hit 30 in. by the second day. The winds helped spawn several tornadoes and damage was estimated at $7.3 billion. Ben said it was the most damage he’s seen in the 16 years he’s been a contractor—but that damage didn’t include his Fortified Roofs.

“We had zero damage on any roof we have done in the past five years. We had three roofs with problems, but only because they had trees fall through them,” he said. Similarly, the Fortified website includes a testimonial from a resident of Mexico Beach, Fl., whose house survived Hurricane Michael in 2018—a Category 5 storm that destroyed much of Florida’s panhandle. There are more stories of homes that weathered storm damage on fortifiedhome.org.

It’s About More Than Money

While the insurance industry and their customers, who are often given insurance discounts for meeting Fortified standards, have financial motivation for improving the resilience of what is often very expensive coastal housing, there are equally important reasons for keeping houses safe and dry during storms. People are often forced to shelter in their homes because of surprise weather events or those that turn worse than expected. If we can prevent deaths and injuries by building stronger houses, it’s a no-brainer. I would also much rather stay in my intact house after a storm than be evacuated to a shelter or spend months in a FEMA trailer like the sweltering versions I saw in New Orleans, many of which made their occupants sick.

More-resilient housing also helps neighborhood businesses recover more quickly after storms. When people are forced to evacuate, they have to buy food and necessities from outside their community. The availability of housing also keeps local workers at their jobs, which helps neighborhood and regional recovery. Finally, I suspect anyone in the construction industry who’s experienced the shortages of building products like roof shingles and sheathing following big hurricanes wouldn’t miss the volatility and scarcity that comes from major storms.

There are those outside and within the building industry that ask if we should even be building in places prone to hurricanes and high winds and hail. Maybe not, but the undeniable appeal of a beach lifestyle means that people are going to build in those places anyway. And when it comes to wind, Tornado Alley and the Gulf Coast get all the headlines, but high winds affect a lot of the country—just look at FEMA’s National Risk Index “Strong Wind” map at fema.gov. Hail is almost as widespread as high winds and more costly in an average year than hurricanes, tropical storms, and tornados combined. Building more resilient structures in more places is the obvious solution.

Higher Cost Where Risk is Higher

Anyone reading this far is probably asking what it costs to build a Fortified Home. It certainly costs more. In addition to higher material costs for additional connectors, impact-rated windows, and fully sheathed walls, there are strict fastening schedules for sheathing and roofing, where nails have to be placed accurately without being overdriven. This work takes longer than conventional roofing and framing, where speed is generally the primary concern.

Projects also require third-party inspections by Fortified-trained inspectors, who—since they can’t be there for the entire roof installation or build—rely on specific (some might say exhaustive) photo documentation of nailing patterns, roof-deck sealing, and other details as part of the certification process for insurance discounts. Every project is different, but Ben estimates a Fortified Roof costs between 15% to 25% more than a conventional roof in his market.

New builds also cost more. The exact number depends on the project, but Ben says the town homes he’s building to the Fortified Gold standard cost 10% to 15% more than the same structure without the Fortified features. When I remarked on the many metal connectors strengthening the shell at every level, he told me that each unit has $20,000 in stainless-steel fasteners and connectors alone. He added that impact-rated windows and doors cost about 50% more than conventional windows and doors. Those figures might seem like a deal-breaker, but the homes he’s building sell for millions of dollars, which helps put the figures in perspective.

Insurance Industry Has Sway

One of the things I find most appealing about Fortified is that the costs are paid for by the homebuyer—and the higher purchase price for a more-resilient house in a riskier location should be offset by lower insurance premiums over the life of the structure. But in fact, while Fortified standards are not code-required, without reaching some of these standards in high-risk areas, you may not be able to get insurance at all, or it may be prohibitively expensive.

Because of the higher price of building, the success of the Fortified standards might hinge on government-funded programs that give grants to homeowners who implement resiliency measures. You can read more about these insurance coverage and resiliency issues in “Why Fortified standards (and others like them) matter” (Building Matters, FHB #322).

Some of you may be thinking that Fortified standards are a case of insurance industry overreach, but I would point out that their influence over building standards isn’t new. Our nation’s first building codes resulted from the huge fires that ravaged Chicago and other major cities during the later part of 19th century. After those losses, the insurance industry pressed for stricter rules on construction, and those efforts worked. I hope these efforts work too.

From Fine Homebuilding #324

— Patrick McCombe; senior editor. Drawings by Christopher Mills.

RELATED STORIES

- Why Fortified Standards (and Others Like Them) Matter

- Combat Extreme Weather With a FORTIFIED Roof

- Protect Houses from Severe Weather with the FORTIFIED Construction Method

- Building Homes to Withstand Storms

- A Sturdy Floor for a Coastal Home

- Podcast Short: Hurricane-Resistant Housing

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Graphic Guide to Frame Construction

Ladder Stand Off

Roof Jacks

View Comments

The pictures of roofs striped of asphalt shingles speak for themselves. Codes should be changed to require using and meeting the shingle manufacturers’ instructions, especially nailing pattern. International Residential Code section R905.2.6 ‘Attachment’ allows installers to meet code with as few as 2 nails per shingle. Totally inadequate.