How to Choose a Building Site

From the city center to the most rural neighborhoods, choosing the right site can have a great impact on your budget, and what you can build.

Before you build, you need a building site — and there’s a lot to do before you can pour a foundation. Finding temporary power sources; managing excavation for cable lines, septic tanks, and wells; planning for zoning setbacks and restrictions; and adding infrastructure can add costs quickly. Here are some considerations to make when considering how to choose a building site.

Finding a Location You Love

For many people, building a custom home is a dream—especially when they can choose the location. The opportunity is equally exciting for builders and architects for whom a custom home can be an opportunity to demonstrate their skills and craft. It also can be very lucrative.

If the already complicated process of building a house—from pouring foundations all the way to the punch list—is a challenging game of checkers, adding the complex task of dealing with site work means leveling up to chess. The right house on the wrong site can bust a budget when builders run into surprising local codes, when excavators get stymied by ledge, or in nearly any instance when a site is near a protected waterway.

For designers and builders experienced with custom homes, the key to finding a suitable site is doing a lot of homework. “The very first thing, whenever you buy a piece of property, is to find out what the rules of the game are for that property,” says Lake Forest, Ill.–based architect Diana Melichar of Melichar Architects.

Picking the right site can require a builder’s understanding of construction, an excavator’s familiarity with local topography, an architect’s willingness to investigate the oddest of local codes, an attorney’s understanding of which variances you can fight and which you can’t, and even a real estate agent’s understanding of the context around the property.

Site Work and the Budget

Building costs vary across the country, as does the price of land. But expect to dedicate between 15% and 25% of the project’s budget to land acquisition. “Twenty percent is the number I have in mind,” says Bryan Uhler of Port Orchard, Wash.–based Pioneer Builders, a high-performance custom and spec builder. “That 20% includes markup, profit, and a real estate fee,” he says. “While there are many variables in there, that 20% would let somebody know if they’re in the ballpark.”

Land cost is one variable, and often it assumes equal access to qualified crews to develop the site and build a house. “How much you spend can be dependent on your area,” says Emily Mottram of Mottram Architecture in Thomaston, Maine. “[Land] will cost more in Portland, Maine, than in Bangor, but access to builders is better in Portland, so even though the land may be cheaper in other areas, your ability to have something built does not get easier.”

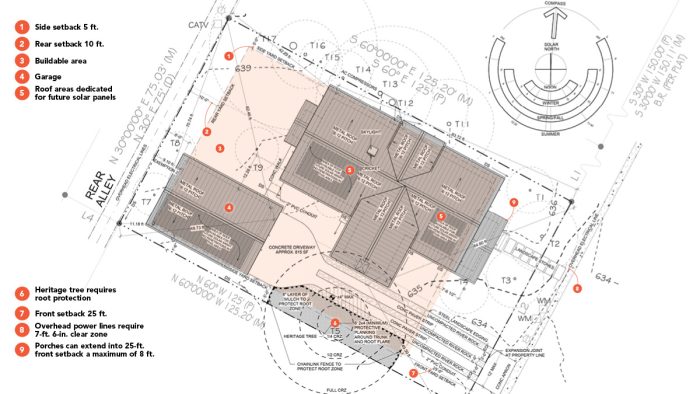

Building Sites in the CityBuilding inside city limits can mean limited lot sizes and copious restrictions. On the Austin, Texas, site shown here, Barley Pfeiffer Architecture had to work with setbacks, impervious cover limits, floor-area ration limits, clearance around overhead power lines, and even a protected heritage tree.  Tight, and Spacious: Even with copious restrictions, a thoughtful site plan can result in a spacious-feeling home. On this tight Austin lot with a house and detached garage, the designers still managed to include outdoor spaces, gardens, and even a big rainwater cistern.  |

Chief among those costs are site development fees, especially if trucks have to travel long distances to dispose of material. “If there’s been any previous commercial or industrial use on the property, you want to make sure the soil has a clean bill of health because it can be expensive to truck contaminates 20 or 30 miles away,” says Adam Boudreau of Kentile Excavating, a Tupper Lake, N.Y.–based site developer. “But even a 500-gal. or 1000-gal. fuel tank that leaked can be expensive to remove, depending on how far that dirty soil has to be chased.”

Some spec builders, like Uhler, have the liquidity to purchase land and fund the construction, but others would likely apply for a construction loan. Lenders typically provide about 80% of the bank’s expected value of the home, for which they like you to have about 20% of the project’s cost in cash.

Along with plans and a licensed builder, a bank might ask to see estimates for site development, as those costs can quickly add up. Depending on the bank and the site location, you might be asked to provide a survey or soil samples to confirm the land is suitable to build on. Construction loans come in a few forms, though a common one converts to a traditional 15-year or 30-year mortgage once the house is complete.

Lot Size and Location

While the ratio of property size to building largely depends on budget, local building and zoning regulations have the final say in maximum house size. Yes, larger lots can typically sustain bigger homes, and working on any urban lot usually means inheriting a defined set of boundaries, but building in rural areas isn’t exactly the Wild West. “Just because you have a large piece of rural property doesn’t mean you can build on every square inch of it,” says Uhler.

Many municipalities, including rural ones, have a total amount of impermeable surface threshold allowed on a lot, which includes anything that jettisons rainwater rather than allowing it to percolate through the ground. Depending on the town, lots might be subject to no more than 10% to 40% impervious surfaces, which can tally the total square footage of the house, a detached garage and/or shed, a patio, a driveway and walkway, and sometimes a second-story deck.

Protected water features are another element that can effectively shrink usable lot size. If a lot has a protected pond, stream, or wetland—one you hopefully discovered before buying—it’s essential to understand how close you can develop without encroaching on protected land.

Mottram’s approach to the decision of how much land you need is more organic: “There could be 30 acres for sale when you only want 10,” she says. “What’s available in your area, and what is the access or lack of access to amenities that you’re looking for?” Asking clients how far they’re willing to be from conveniences like the grocery store or public transportation, and gauging how much privacy they require, helps factor into picking the right lot, which then sets the guidelines for how large a home you can build.

With the exception of very large properties or ones in rural areas, the size of a driveway doesn’t usually factor into a site’s suitability; increasingly, however, space for solar may. “If a client wants to have solar, part of that might be a ground-mounted array,” says Amanda Weglinski, a designer and project manager at timber-frame prefabricator Bensonwood, who adds that some of her projects might require about half the home’s square footage in cleared land for an array near the house.

Beyond Setbacks, HOAs

Experienced contractors are familiar with navigating local regulations that deal with basics like setbacks—the distance from the property line within which you are typically not allowed to build. But when it comes to picking and developing a new site (or replacing an existing building in town), a project’s success frequently hinges on the due diligence done before a lot is purchased. In an urban setting, parts of the town that contain historic districts can add another layer of rules—what architects call overlays—that govern decisions with potential real budgetary impacts, such as window styles, roofing, and siding materials.

Increasingly, though, homeowners associations also have overlays that add to the complexity, and these can be where builders least expect them. “Homeowners associations have a certain connotation that comes with a neighborhood that was developed, and they formed an HOA to administer the use of the swimming pool and the common facilities,” says Austin, Texas–based architect Peter Pfeiffer of Barley Pfeiffer Architecture. “But then you’ve got neighborhood associations, and if you don’t follow their rules it can make your life miserable.”

For Pfeiffer that means developing an intimate knowledge of the city of Austin’s 10 different districts, each with its own three or four neighborhood associations, which might have only slightly different regulations. These neighborhood associations can sometimes be difficult to discern at street level, since they are not always in the historic center of town and the homes might not all have the same architectural style the way a planned community often has.

Today most of these regulations are available online, which is helpful because builders and homeowners can’t always rely on getting an answer from a municipality’s busy building department. “If the homeowner calls the city and it’s a little town, that’s one thing, but when you’re talking about an urban area like we have, two million people in the 10th largest city in the country, you have to make sure you find out who at the city you’re talking to and then double-check what you heard,” says Pfeiffer.

Boudreau echoes the sentiment, especially in purchasing a plot of rural land: “The local municipality is a great resource because they usually are going to know the road you’re on and the local power authority guys, and they’re going to be able to tell you if someone else just built on that road and if they spent $100,000 on site development.”

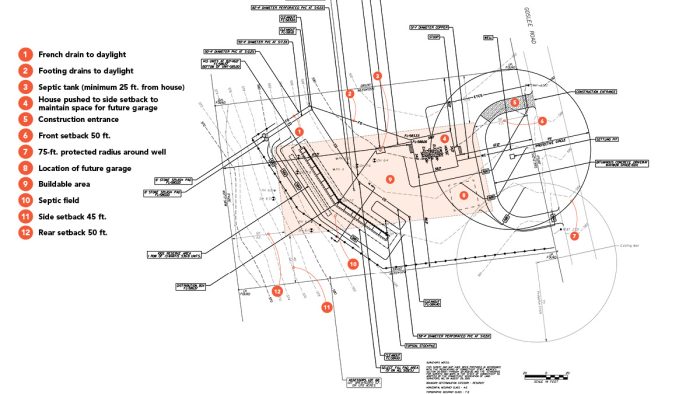

Building Sites in the SuburbsOn a lot of nearly two acres like the one shown here, it can be challenging to fit everything within the generous zoning setbacks and health department restrictions on wells and septic systems. The well alone requires a 75-ft. radius within which no septic systems, including the neighbors’, can encroach. Keep in mind that these examples are specific to their local building departments.   Engineering Inspiration: In some areas a licensed engineer is required to develop the site plan, particularly where septic systems are included. Plymouth, Conn.–based Robert Green Associates turned this simple sketch from the owner/builder into a permittable plan.  |

Consider Utilities and Infrastructure

Even with the cost fluctuations of building materials, the budget for a house can feel far more transparent, and easier to pin down, than what’s required to turn an undeveloped parcel into one suitable to live on. Within the city, the location of utilities—gas, water, and waste—is usually fixed at the street. Keeping utilities where they are is one way to keep costs in check. But in rural settings, extending utilities to a remote lot can tank a budget. “On a current project in Massachusetts, it was like $50,000 just to get electric from two lots away, across the street to the project’s curb,” says Weglinski.

Knowing where the utilities are ahead of time arms builders with a potential negotiating chip with the land’s seller. “We’re doing a project right now that if we didn’t get the credit from the electrical utility we would have to pay, maybe, $14,000 for service,” says Uhler. “Knowing up front what your utilities extend to is important, and you can always negotiate that cost with the land seller.”

Boudreau says the power company usually gives you about 200 ft. of secondary power, but anything beyond that might require wiring the site for primary power. “If that happens, your planning could be messed up because it might take a year to get that approved,” he says, “and I’ve seen costs as high as $100,000 just for electricity.” Running gas can be nearly as expensive, which prompts many rural builds to rely on propane tanks.

Researching the site beforehand helps factor site costs into the budget, and knowing about the soils early on means less sticker shock when it comes time to execute seemingly routine tasks like installing a well. “Visit the site,” Boudreau says. “Searching Google doesn’t necessarily give you the right answers, and that’s when costly mistakes are made.” An internet search might reveal the average cost of drilling a well is up to $12,000, but that can be misleading.

“Maybe your well is 600 ft. deep and $12,000 covers the cost of the drilling, but you have to hire an excavation contractor to build a road to your well, and then I have to build a pad because a giant well-drilling rig is super heavy,” he says. “And does that price include running water into the house and electricity to the pump?”

With an undeveloped piece of land, it’s never too early to find the right excavation contractor who is familiar with the area, the soils, and the topography. Something as utilitarian as building 18-ft.-wide construction roads to accommodate everything from pickups to cranes can cost upward of $30,000 once the topsoil is removed, replaced with fill, and graded. Access gets more expensive if the lot is wooded, so a cleared lot is, according to Boudreau, always a less expensive option to develop, though you’re paying for that too.

“If you buy a cleared piece of property, you’re paying somebody else for all of that work that they did,” says Uhler, who has paid between $25,000 and $55,000 just to remove trees and has, on occasion, purchased a lot with valuable timber he could sell to help offset the costs. Likewise, the topography can add thousands to the site development fees to fix unsafe conditions, like a driveway that slopes too aggressively to meet local codes, or grading that directs water toward the foundation.

A relatively flat, cleared lot is almost always less expensive to develop than a steep wooded one—unless you run into ledge or bedrock. On a recent job, Boudreau brought in a blasting contractor to remove close to 1000 tons of rock, easily adding $50,000 to the site development fee.

Planning for Solar

Many builders plan for solar panels, even if the budget won’t accommodate them while the house is being built. “We always plan for solar orientation,” says Mottram. “It’s not always possible to orient our buildings with optimal solar. But what may be more important is for us to build simple structures so that dormers, roof jogs, and other complicated features don’t interfere with the ability to put panels on the roof.”

Pfeiffer also designs all new homes with solar in mind. He says, “Almost every home we’ve done since the late 1990s is designed with the right-pitch roof with at least a significant amount of roof facing the right direction for solar and then prewired for solar—and that’s fairly cheap and easy to do.”

Solar panels or a large ground-mounted array isn’t always in the budget. However, employing a design that maximizes passive solar gain is often a matter of working with the right architect sooner rather than later.

“Before you worry about trying to produce solar energy, the most important thing is to reduce the need for energy,” Pfeiffer says. “And oftentimes a hip roof will help us save a lot more energy because it allows us to shade more windows and more walls than a gabled or shed roof.”

Don’t Skimp on Landscaping

Setting aside a sod budget will, in the end, hamper a new home build—especially one on a site you’ve developed. Landscape architect Steve Doe of Portland, Maine–based Knickerbocker Group thinks that setting aside 20% of the overall budget for landscaping makes sense to handle everything from plants to patio spaces.

And at least part of that budget should be allocated to stormwater management. Doe and his colleague, landscape architect Kerry Lewis, work in a lot of municipalities where any new building is required to store the roof runoff on-site, and that can mean engineering massive dry wells.

Nearly all landscaping plans can be phased in over time, which helps to defray some of the up-front cost. But while a pool might not be part of the plan when the house is finished, working with a landscape architect to develop a comprehensive overview of the site ensures that access won’t be a problem later.

“If you want to do a swimming pool later, that’s great,” Lewis says. “But you have to make sure you can get the equipment to that spot after everything else is done—so don’t put a gazebo in the way of the future pool.”

Before You Build Reality ChecklistEven on an easy building site that doesn’t require clearing trees or blasting ledge, there’s a lot to do before you can pour the foundation for a new home. And as you build, you’ll need to add infrastructure and connect to utilities. The price of land development and site work can add up fast. Here are some of the things you’ll need to be prepared for.

|

— Sal Vaglica; former editor at This Old House magazine, has been writing about home improvement for over 15 years. Photos by Brian Pontolilo, except where noted.

RELATED STORIES

- There’s No Such Thing as a Perfect Building Site

- How to Create a Site Plan

- Taking Advantage of a Difficult Building Site

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Affordable IR Camera

8067 All-Weather Flashing Tape

Reliable Crimp Connectors