Restoration Mistakes & Wins

From plumbing failures to environmental near disasters, OHJ staffers dish on our worst and best moments.

Pictures don’t always tell the full story behind what it means to own, restore—and perpetually maintain—an old house. Like most of our readers, OHJ staff members have restored key features and remodeled kitchens and bathrooms as money and time permit.

To me, overcoming problems on the way to creating beautiful or at least useful spaces is perhaps the most exhilarating part of restoration. I say that as I embark on my summer project: stripping multiple layers of caked-on paint from the floor of a large, screened-in porch.

For others of us, it was adapting the design of a mid-1800s beadboard sink cabinet into a seacoast kitchen remodel … or choosing a much-loved wallpaper for a tiny powder room. I’d almost rather have a problem that requires professional assistance to address; an example is the sudden incursion of water in the buried oil tank that I knew could be an issue one day. While there are so many stories we could tell, we’ve chosen the best (worst?) from only our current houses.

— Mary Ellen Polson

|

|

Why We Do It

My 1904 seaside cottage was marketed as a teardown. Among many desecrations, the front porch had been torn off and the main staircase removed. I knew what it must have looked like, however, and proceeded to put too much time and money into saving it.

“Why do you buy these pathetic old houses?!” — Patty’s Mom, 1992

Knowing the house leaned toward English Arts & Crafts, I coveted for it the fairytale staircase in William Morris’s Red House in Bexleyheath, South London. That house was then in private hands and the Phaidon book about it not yet published. I gave a blurry photo and a vintage illustration to my bewhiskered stairbuilder, who said nothing. A few days later, he returned with full-size shop drawings.

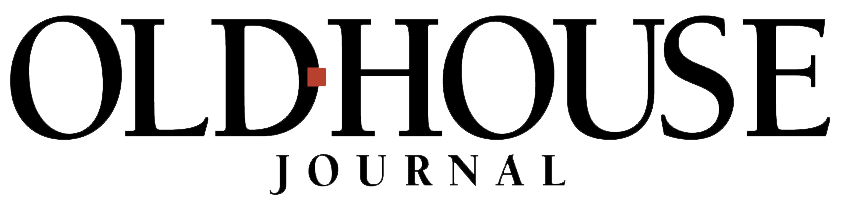

The stair is about 2/3 scale as my house has lower ceilings than Red House. When they were little, my boys called it “the Castle Stair.” The rounded kitchen island came about after a visit to Castle Tucker, a Historic New England property. The model was built by boatbuilders, perfect for Gloucester. My version conceals a soapstone sink, dishwasher, and bins.

Beware What Lies Beneath

I’ve made my share of mistakes. We installed a hand-held shower and drain for rinsing beach sand off kids and dogs. We shut the water off in the fall. All seemed well until my son gave Loki a pre-season bath. With frost still possible, he went to shut the water off and discovered water cascading into the crawl space.

Ripping off shingles (and then more shingles) exposed the extent of damage. The corner sill and post, sheathing, and even some of the fir porch decking had rotted.Several things had gone wrong. Water lines were in an exposed corner of an unheated crawl space.

|

The turn-off valve was in a cold zone and there was no good way to flush remaining water from the pipes. The inevitable leak was undetectable from outside. In part due to inadequate flashing, water ran undetected into the corner of the house every summer.

After carpentry repairs, I replaced the shower apparatus with frost-resistant exterior-grade brass fittings and better flashing. The plumbing is now configured so I can slide it out from the exterior and store it each winter. Now we do a two-person inspection each season.

— Patricia Poore

Not All Remodeling is Bad!

One of the best features of our American Foursquare near the harbor is the wide and deep front porch. It hasn’t always been this way. In the 1950s, the entire house (some part dates to 1879) was improved with Colonial Revival mantels, etc.; one upgrade was expanding the ends of the porch nearly 4′ past the columns.

The house had had a different set of steps and a narrow porch only about 6′ deep. We’re happy to have inherited a remodeled porch that affords two outdoor rooms: one for plentiful seating and a view, the other for a nap-size porch swing.

The extended porch boards see more weather than the original deck, but not enough to explain why the old fir remains intact as the newer boards (which we keep painted) rot and splinter every few years. That dense old fir is hard as a rock.

— Becky Bernie

Starting From Scratch

My husband, Jeff King, and I looked for an old house starting out but couldn’t find one with the integrity we wanted. We decided to build our own “old house,” mostly with our own lumber (from the site) and labor. To match the vernacular, I chose a simple Greek Revival style with curved cornice mouldings and returns, copied from houses on Cape Ann.

A talented woodworker and machinist who can build anything out of wood or metal, Jeff hand-planed these. The front—intended to look like the “oldest” section—is traditional 2×6 construction, while the back half is post and beam. The 4×8 and 8×12 cross beams, most of the flooring, and 2′-wide horizontal interior paneling in the living room all were milled from mature pines on the property nearing the end of their natural lives.

Inspired by my work with Old-House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes—and by black-and-white pictures of old New England houses I found in the OHJ library—I planned an interior with a sampling of compatible styles—Candace Wheeler’s ‘Carp’ wallpaper, William Morris papers and textiles.

We also used salvage: Doors and trim mouldings in the hall came from a house being razed down the coast. We added Swedish-inspired cabinets to reflect my Scandinavian heritage. One project to come is tiling the arched fireplace in the front section. I modeled it after First Period (Colonial) fireplaces and those at Standen, the British National Trust property.

— Inga Soderberg-King

Determined to Add a Powder Room

Our 1929 American Foursquare has the typical shortcomings of the era: no bathroom on the first floor and only a single coat closet. When my husband and I realized we’d willingly sacrifice the closet, we converted that tiny space (a scant 3′ x 4′) beside the kitchen into a cute and carefully designed powder room.

|

|

Many period-style toilets were just too deep for our space, as we needed 21″ between toilet and sink to meet code. I made mock-up toilets to scale, out of cardboard boxes. Measuring only 16″ wide x 24 5/8″ deep, the Icera model we chose fit perfectly opposite the tiny corner sink and corner medicine cabinet I’d found after intense internet searching.

Then came the fun part: using handmade art tiles from Carreaux du Nord as a backsplash. In a rich yellow gloss glaze, two rabbits and two squirrels represent our backyard wildlife! I had long adored Trustworth Studios’ ‘Squirrel & Vine’ wallpaper, a C.F.A. Voysey design from 1930.

|

Now I finally had a place to put it! We wanted a period wall sconce but not the shadows one would create in the small space. We opted for a low-profile overhead light-and-fan combo. The automatic fan gives the occupant a sense of noise-blocking privacy.

I painted the plastic cover the same pale aqua as the ceiling so you don’t even see it. As a last touch, we finished the floor in 1 ½” hex real marble floor tiles in a pale green colorway, tying together the colors in our Birdie Bath.

Oh but Bumps Along the Way

The powder-room project was part of a modest overhaul of the kitchen. With glee, we’d peeled 1980s pink vinyl off walls. Though tired, the 1950s wood cabinets were solid, so my husband, Steve Smith, sanded and painted them a vivid green that suggests my collection of majolica.

We switched out grubby hardware for heavy Amerock pulls in a satin-nickel finish. We replaced dingy, dented vinyl flooring with Forbo’s sheet Marmoleum in the Seashell design, reminiscent of 1930s jaspé patterns. All good until bumps appeared in the flooring.

The installer identified the problem: sections of the old vinyl floor (which they elected not to remove) were glued to the substrate but others were not. The new linoleum literally sucked sections up, creating bumps. The installer, a local company of good reputation, removed all layers and relaid new Marmoleum.

— Lori Viator

Disaster Averted

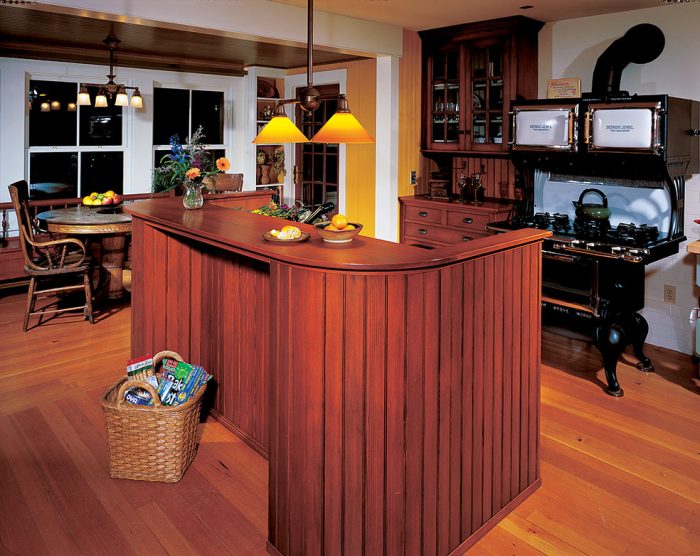

After living in a series of historic houses and prewar apartments during our nomadic careers, Jim and I bought the 1913 Catskills “rusticator” that’s now our home. It came with several potential big-money pitfalls, but it was of the Arts & Crafts period, and we’d never owned one of those. Be careful what you wish for.

We thought we had dodged a bullet when we learned the buried 1,000-gallon oil tank was protected by a cathodic system that supposedly prevents corrosion (thus the steel tank won’t leak). An oil leak would pollute the soil and groundwater, causing environmental risk to nearby lakes and streams—and in our case, our well.

Remediation from a leak that pollutes a nearby water source can cost $100,000 or more. To be on the safe side, we bought insurance to protect us should we ever need remediation. All good until a technician doing a routine furnace inspection announced that so much water had mixed in with the oil in the tank, it could destroy the furnace. Oops.

|

|

|

One winter morning, a crew duly arrived. These days, old oil tanks aren’t pulled out of the ground and discarded; they’re abandoned in place after emptying. While workers installed the smaller (and much too prominent) above-ground tank in our side garden, others removed dirt and gravel and finally the (pre-paid!) oil, at last swabbing with oil-absorbent (oleophilic) pads.

As the building inspector looked on, a worker began cutting an inspection hole in the bottom of the tank. A gusher of water hit him in the face. “There’s no way that tank was leaking if there was that much pressure inside,” the inspector declared.

Given the OK, the backhoe operator filled the tank with gravel, buried the hole, and leveled the site. Our mini-disaster cost between $12,000 and $15,000. As there was no need for remediation, the insurance didn’t kick in.

Out of the Gloaming

Our house looks vaguely Dutch Colonial but its double-height interior comes as a surprise. Finished in dark-stained pine, the vast living room has a 19′-high ceiling. A dogleg staircase leads to an open gallery above. I will never paint that room.

During the day, an enormous north-facing window and a bay window on the west side let in the light. On sunny days, beautiful dapples cascade through the old glass to land on mellowed boards. At night, however, art on the walls disappears into the gloom.

|

Inspired by a 1929 fixture in a nearby tourist hotel, I found a pair of Tudor Revival pendant lanterns at an antiques store. Now fitted with pale-yellow Kokomo opalescent art glass, they hang in the gallery. I wish I’d chosen mica, but ordering glass precut to size was much simpler.

Hanging the lanterns was a challenge. In a normal house, an electrician cuts a hole in the drywall for an electrical box. Not here. Running power meant installing metal raceway conduit to new boxes mounted on ceiling boards. I wisely painted lengths of conduit and boxes before installation.

— Mary Ellen Polson

RELATED STORIES

- What to Look for When Buying an Old House

- Video Vault: Inspecting Old Houses

- A New Floor Plan Saves an Old House

Photos courtesy of the homeowners except where noted.

Our People With Old Houses

Becky • Foursquare (Date Unk.) • Gloucester • Here 39 Years

Brian • Queen Anne 1899 • Seattle • 40 Years

Gordon • Family Farm 1880s • Lackawaxen, PA • 30+ Years

Heather • Farmhouse 1751 • Haymarket, VA • 19 Years

Inga • Greek Revival Designed 1996 • Gloucester • 27 Years

Judy • Gothic Revival 1851 • So. Royalton, VT • 30 Years

Lori • Foursquare 1929 • Gloucester • 4 Years

Mary Ellen • Catskills Camp 1913 • Bearsville, NY • 4 Years

Patty • Tudorbethan 1904 • Gloucester • 31 Years

Pete • Sears Foursquare 1924 • Wash., DC • 40 Years

Regina • Folk Victorian 1910 • Gloucester • 40+ Years

And more — we tend to stay put after restoration!

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

All New Bathroom Ideas that Work

Get Your House Right: Architectural Elements to Use & Avoid

A Field Guide to American Houses