Dehumidifying With Heat-Pump Water Heaters

Dehumidification is listed as a selling point for HPWHs, but are they actually effective at lowering humidity?

Several manufacturers and advocates of heat-pump water heaters highlight lower operating costs and dehumidification as selling points. Currently, I have a resistance-style electric water heater, and I run a portable dehumidifier much of the year to keep my basement from smelling moldy. Can I really dehumidify my basement and make hot water with a heat-pump water heater?

— Jamie Ozolek; Forest Hills, Pa.

Contributing Editor and HVAC Expert Jon Harrod Replies:

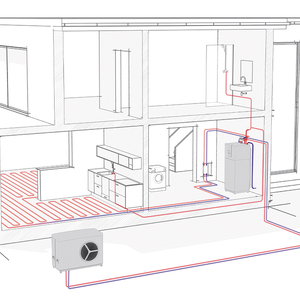

Dehumidifiers and heat-pump water heaters (HPWHs) are similar appliances. Both use a refrigeration cycle to move heat from one place to another, and both have a cold coil that provides a condensing surface that can collect liquid water from water vapor in the air.

However, dehumidifiers and HPWHs run their refrigeration cycles based on different criteria, which is important when answering your question. While researching a Green Building Advisor article on water-heater dehumidification, I found two relevant studies on this subject. William Murphy of the University of Kentucky did research on his Kentucky home and presented at the 2016 International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference.

Let’s Look at the Data

Data collected from 2010 to 2015 showed his HPWH produced less than 0.2 pints of condensate per day in winter and about 0.9 pints per day in summer. For comparison, a small dehumidifier can remove 35 pints per day and a large one 200 pints or more.

Another 2013 study by Carlos Colon of the Florida Solar Energy Center examined HPWH performance in a test building similar to a Florida garage and assumed the daily amount of hot water consumed by a four-person household. Even in what might be considered ideal conditions—a warm, humid space and relatively high hot water use—the HPWH only produced 3.2 pints of condensate per day.

Testing at my own two-person household revealed that my HPWH could theoretically remove up to 35 pints per day if the compressor ran continuously in warm, humid conditions—but since it is not designed to operate this way, it in fact provides almost no dehumidification.

Methodology and Results

I measured HPWH condensate production, first with the basement dehumidifier running and then with it off. Over 24 days, with the dehumidifier maintaining an average relative humidity (RH) of 57%, I collected only 4.25 pints of condensate from the HPWH, or about 0.17 pints per day. When I turned off the dehumidifier and let RH drift upward above 70%, condensate production for the HPWH produced 6.5 pints over the next five days, an average of 1.3 pints per day.

Despite the nearly eightfold increase, its condensate production is still very low compared to my dehumidifier, which produced 36 pints per day under similar conditions. There are two primary reasons why. Using data from my energy monitor, I saw that my HPWH turned on about 1.2 times per day and ran for an average of about 68 minutes, or about 5% of the time, severely constraining its ability to dehumidify.

It also appears that most of the condensate never makes it to the drain. When a water-heating cycle starts, it typically takes a few minutes for the evaporator coil to get cold enough for condensation to occur. Only when sufficient water accumulates does it begin to drip into the drain pan and run down the drain.

When the cycle ends, any water on the coil and in the drain pan evaporates back into the air. For a typical 68-minute cycle, much of the condensate remains on the coil and in the drain pan. I’m guessing most of the condensate I collected was produced during 3-hr. run cycles on laundry days.

What It All Means

This leads me to believe that high-occupancy households with more hot water use would see more moisture removal from a HPWH. Properly constructed concrete foundations with functional exterior drains, effective waterproofing, and a subslab vapor barrier would also reduce the amount of dehumidification needed. And keep in mind that any space you’re trying to dehumidify should be considered “conditioned,” so keep windows and doors closed or you’ll be trying to dehumidify all of the outdoors.

But even in the best-case scenarios, I think of HPWH dehumidification as an intermittent and incidental benefit of making hot water. HPWHs operate in response to hot-water demand, not indoor humidity. As a result, they don’t run often enough to provide adequate dehumidification.

RELATED STORIES

- Heat-Pump Water Heaters

- Advantages of a High-Performance Heat-Pump Water Heater

- Efficient Hot Water With Less Noise

Need help?

Do you have more questions about dehumidifying a basement with a heat-pump water heater? Get answers you can trust from the experienced pros at FHB. Email your question to [email protected].