FAQs on HPWHs

Get the answers to common questions about heat-pump water heaters like efficiency, cost, sizing, and more.

With their potential for cost savings, low energy use, and long lifespan, heat-pump water heaters (HPWHs) offer clear advantages over traditional water heaters. This article explores how HPWHs work, their benefits, and key considerations like cost, energy savings, sizing, and installation. It also compares the operating costs and energy efficiency of various water heater types, and includes specifications for four HPWH models.

The Heat-Pump Water Heater Learning Curve

Heat-pump water heaters, or HPWHs, are gaining popularity because they can provide ample hot water with low operating costs and a lifespan comparable to other tank-style water heaters. But this relatively new technology has a few quirks, and poor design and installation practices can lead to complaints about noise, comfort, and insufficient hot water.

As an installer and project manager, I’ve been involved in dozens of HPWH installations. Here I’ll describe how HPWHs work and answer some frequently asked questions to help you select the right one and optimize its performance.

How Much Does a HPWH Cost?

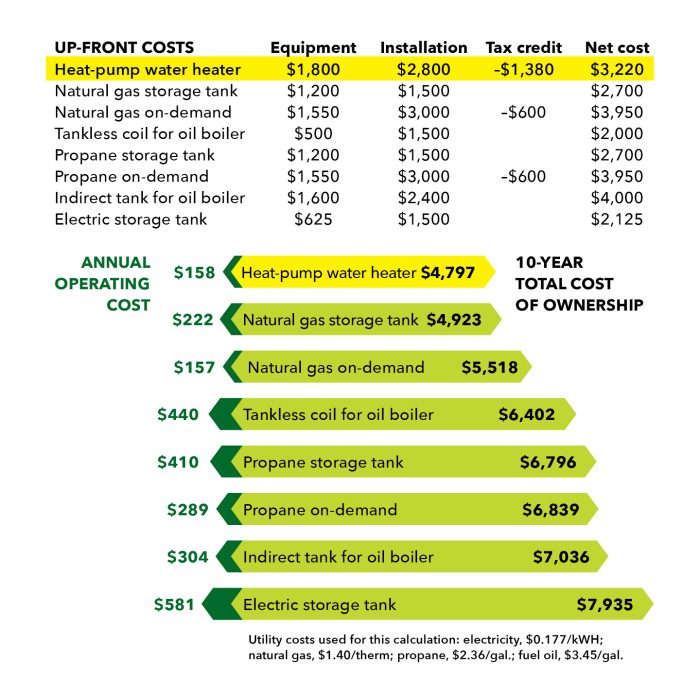

HPWHs cost more than electric-resistance or gas-fired tanks. A 50-ga. model starts at around $1600; 80-gal. models can cost upwards of $2700. Labor and additional materials typically run between $1500 and $3000. Factors affecting installation cost include whether a new electric circuit is needed and the difficulty of running drainpipe for the condensate, which is produced as the HPWH absorbs heat from the air.

The up-front costs of HPWHs can be offset by a 30% federal tax credit (up to a maximum credit of $2000) and, in many areas, state and utility incentives. The Energy Star program provides the HPWH Product Finder, a searchable database of more than 300 eligible models, along with information on rebates by zip code.

My utility offers $700 toward the installation of a qualified HPWH. Combining this incentive with the federal tax credit would bring the net cost of a HPWH installation from $4600 to $2730. With a net cost in the same range as other water-heating options and a lower operating cost, a HPWH can make good economic sense.

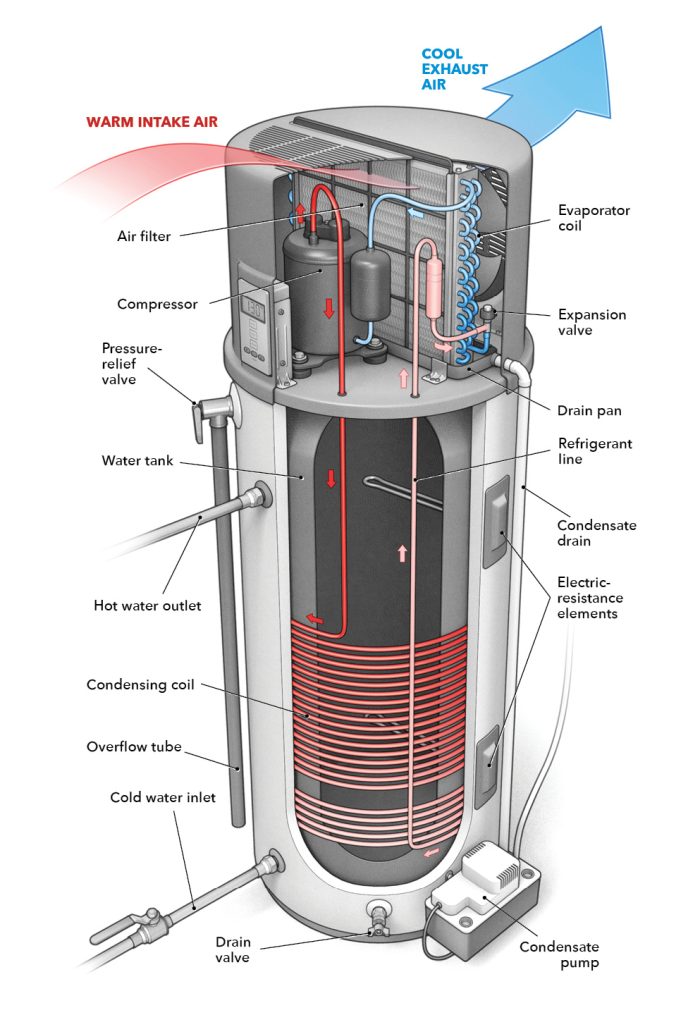

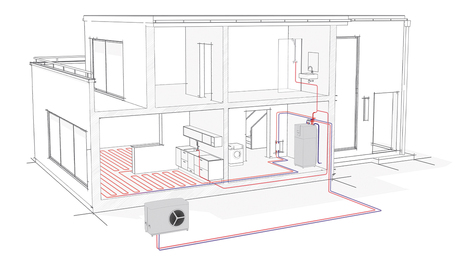

How Heat-Pump Water Heaters Work: Hot Water From Warm Air HPWHs work by extracting heat from the surrounding air and transferring it to the water inside the tank. Specifically, the heat pump’s fan pulls ambient air from the room into a heat exchanger, warming the refrigerant. The heat-pump compressor—much like that found in a refrigerator or air conditioner—compresses the refrigerant, raising its temperature. The hot refrigerant then flows to the condensing coil, where it transfers heat to the water. If the air moving through the HPWH cools to its dew-point temperature, water condenses on the evaporator coil and drips into a drain pan. From there, this condensate can be piped or pumped to a drain. |

How Much Energy Will It Save?

HPWHs heat water by a different mechanism than fossil-fuel or conventional electric systems, allowing them to achieve extremely high efficiencies. Fossil-fuel water heaters burn natural gas, propane, or oil, and a fraction of that heat—in the best tankless systems, more than 95%—is transferred to the water. Conventional electric water heaters run current through resistance elements similar to those in a toaster or space heater, converting electric energy to heat with 100% efficiency.

HPWHs use electricity to power a vapor compression cycle like that in a refrigerator or air conditioner, capturing heat from the air and transferring it to the tank. In doing so, they can achieve heating efficiencies higher than 300%: Each kWh used yields more than three times as much water heating as one kWh of resistance heat.

Dollar savings will depend on household hot-water usage, local electric prices, and the availability and cost of other fuels. A HPWH will have an operating cost about 70% lower than an electric-resistance tank and will almost always be significantly more affordable to operate than the most efficient oil and propane systems.

In areas with average electric prices, HPWHs may have lower operating costs than even instantaneous natural-gas water heaters. Heating water with HPWHs also reduces CO2 emissions, even in areas where the grid is powered mainly by fossil fuels.

What Size Do I Need?

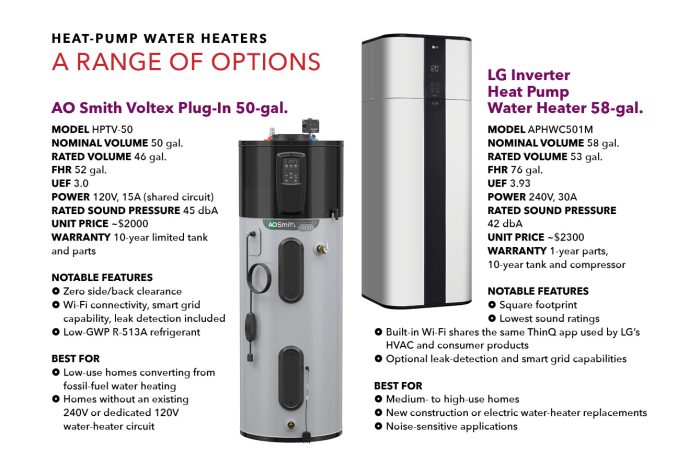

A water heater’s first-hour rating (FHR) is the number of gallons of hot water it can supply in an hour, starting with a fully heated tank. Measured under standard test conditions set by the U.S. Department of Energy, it reflects a combination of tank size and recovery rate (how fast the unit heats incoming water). Fossil-fuel water heaters have high recovery rates, giving them higher FHRs than similarly sized electric or heat-pump water heaters.

A 240V HPWH has resistance elements comparable to those in conventional electric tanks. In the default “hybrid” operating mode, the heat pump provides primary heat, and the resistance elements energize when the heat pump can’t keep up. The FHR reflects the combined output of the heat pump and resistance elements. A 120V HPWH model may have small resistance elements or may lack them entirely. In either case, its FHR is less than similarly sized 240V models (more about voltage below).

If a HPWH is sized correctly, the efficient heat-pump mechanism will provide most of the heating. In a slightly undersized system, resistance elements may engage more often, increasing electric costs. In a severely undersized system, users will run out of hot water during periods of peak demand.

HPWHs are available in nominal sizes from 40 gal. to 80 gal. FHRs range from around 45 gal. for a 40-gal., 120V unit, to 85 gal. or more for an 80-gal., 240V model. The best way to determine what size you need is to fill out a worksheet or online calculator to estimate your peak hot water demand. I like the State Xpert Water Heater Selection Tool (at statewaterheaters.com), which makes recommendations based on shower length and timing, tub size, available space, and geographic location.

Most of the customers I’ve worked with have chosen a 50-gal., 240V model. This choice has worked well in my home; we’ve never run out of hot water, even during holidays when we’ve had up to seven occupants. If you find yourself on the cusp between two sizes, weigh the costs and benefits of upsizing. A larger unit will cost more and take up more space. But it will also use less resistance heat and perform better during a rapid draw such as filling a bathtub.

Heat-Pump Water Heaters: Key CriteriaHere’s a short rundown of the most important criteria to consider when comparing HPWH specs.

|

Should I Choose a 120V or a 240V Model?

Most 240V HPWHs require the same 30A circuits and double-pole breakers used by conventional electric tanks. The highest FHR and efficiency ratings (Uniform Energy Factors) listed on the Energy Star website belong to 240V models, and 240V HPWHs are the logical choice in new construction and when replacing an existing electric tank.

In the last few years, manufacturers have begun offering 120V HPWHs that can plug into existing receptacles. These models can make sense for customers who wish to switch away from fossil fuels while avoiding the extra cost of a new 240V circuit. Using an existing 120V circuit can also make the emergency replacement of a fossil-fuel water heater with a HPWH easier.

Another case for 120V water heaters occurs when the extra load of a 240V water heater would exceed the amp rating of the existing electrical panel or service conductors, necessitating an expensive upgrade. In my experience, this situation is rare. Service-sizing calculations done using the methods described in the National Electrical Code (articles 220.83 and 220.87) usually show that a 240V HPWH won’t, on its own, push an electric service over capacity.

Lower-powered 120V models such as the Rheem Performance Platinum Plug-in, which draws about 440W, can share a 15A circuit with other loads. The Rheem ProTerra, which draws about 1100W, has a more powerful compressor and faster recovery; it requires a dedicated 15A circuit. If the home already has a dedicated circuit for an existing power-vented gas or propane water heater, the more powerful model may be a better choice.

Before opting for a 120V HPWH, carefully calculate your peak hot water demand. A 120V model, with its slower recovery, may not meet the need of a higher-use household.

How Much Space Will It Require?

A HPWH’s top-mounted components—compressor, fan, evaporator coil, and air filter—make a HPWH taller than a conventional electric or fossil-fuel tank with the same rated volume. This, plus the larger tank size needed to deliver the desired FHR, can cause problems in older homes with low basements and narrow doorways.

Installation instructions show the clearances needed around the unit. Some models, such as the State Premier AL Smart Hybrid Electric, place the service connections and air intake and exhaust openings on the top or front of the unit, allowing for installation in tight spaces like closets and alcoves. Others require clearance on multiple sides.

Instructions also specify minimum air temperatures needed for heat-pump operation. Some units will switch to electric resistance when the air drops below 45°F. Others, such as the LG Inverter Heat Pump Water Heater, can continue to operate in colder air.

In the southern U.S., HPWHs are often installed in garages, where they can draw energy from the warm unconditioned air. In northern states, tempered areas like unfinished basements usually work better. HPWHs can also be installed in conditioned spaces, so long as care is taken to mitigate mechanical noise and comfort issues caused by the discharge of cooled air (more below).

HPWHs require sufficient air from which to extract heat. Early recommendations set the minimum volume of an enclosed room at 700 cu. ft. (i.e., a 7-ft. by 10-ft. by 10-ft. room). More recent research indicates that HPWHs can operate efficiently in smaller spaces. State Water Heaters, for example, recently reduced its required room size to 450 cu. ft.

Volume requirements can be reduced further if the mechanical room or closet has a fully louvered door, high and low transfer grilles, or a high grille plus a sizable door undercut. In very small spaces, a high grille plus a flexible outlet duct (attached to the air inlet or outlet with a manufacturer-supplied adapter) or ducts on both inlet and outlet may be required.

Will It Make My House Cold in the Winter?

HPWHs extract heat from the air that passes through them, cooling it by 10°F or more. In winter, this cooling increases the load on the heating system, but the impact is relatively small. One study of HPWHs in nine Michigan basements failed to detect a noticeable impact on home heating use. The same study found that basement air temperatures dropped by an average of 2.3°F during HPWH operation but recovered rapidly at the end of each cycle.

In cooler weather, the air coming out of a HPWH can cause discomfort for occupants nearby. That’s one reason I prefer to locate a HPWH in a space such as a basement. If it’s necessary to put it in a conditioned space, try to discharge the cool air to a hallway, stairwell, or mechanical room so it can mix with warmer air before it reaches higher-use areas.

Heat-Pump Water Heaters: Cost ComparisonsHow do the costs associated with owning and operating a heat-pump water heater compare to those of owning and operating other types of water heaters?

|

What About the Noise?

While design improvements have reduced HPWH sound levels, fan and compressor noise is still a concern. Several current models are rated at 42 db to 45 db, comparable to a quiet refrigerator or dishwasher. Still, individuals vary greatly in their sensitivity to sound, and I’ve heard reports of measured noise levels significantly higher than manufacturer’s ratings.

Keeping HPWHs away from bedrooms, home offices, and other quiet spaces reduces the possibility of noise complaints; silencers for ducted air streams can help too. HPWHs installed on wood-frame floors may benefit from vibration-dampening pads.

Does It Dehumidify Too?

In the summer, HPWHs provide a small amount of “free” cooling and moisture removal. If the air passing over the HPWH’s heat exchanger cools to its dew-point temperature, condensate will form, drip into a drain pan, and run into a drain.

But because a HPWH operates in response to hot water demand, not humidity levels, it’s not a substitute for a dehumidifier. (For more detail on that topic, see my comments in “Ask the Experts” in FHB #328.)

What’s the Life Expectancy?

Most sources list a HPWH’s life expectancy at 10 to 15 years, similar to conventional electric and fossil-fuel tanks. But HPWHs have more moving parts and therefore more potential points of failure. Although fans and capacitors can be replaced, the compressor and evaporator are, in general, not serviceable in the field. If these components fail, the unit reverts to resistance mode until it is replaced.

Some contractors and homeowners have reported a higher-than-expected failure rate for HPWHs. One researcher I contacted, speaking off the record, speculated that this may stem from skilled-labor shortages and resulting quality-control failures during the pandemic.

A contractor I spoke to reported refrigerant leaks on several relatively new HPWHs. He stated that the manufacturer honored its warranty, providing replacement units and an allowance for labor. He also noted that manufacturing problems leading to the leaks appear to have been resolved.

Heat-Pump Water Heaters: A Range of Options

|

What’s the Typical Warranty?

Warranties on HPWH tanks and parts range from six to 10 years. Given the high equipment cost and the history of problems, I’d be inclined to opt for a unit with a longer warranty. I would also speak to my contractor about their experiences with the products they offer.

The same maintenance steps recommended for any tank-style water heater—annual flushing of the tank and temperature/pressure-relief valve, and replacement of sacrificial anodes as needed—can extend the life of a HPWH. In addition, the air filter on the top of the unit should be inspected and cleaned regularly.

Where Can I Find Out More?

The Energy Star program offers a 17-page “Heat Pump Water Heater Guide,” which describes best practices for HPWH design and installation (energystar.gov). That’s a good place to start.

— Jon Harrod; contributing editor, HVAC project manager, and building science consultant.

RELATED STORIES

View Comments

The article on Heat Pump Water Heaters failed to discuss the option of venting the unit to (and from) the exterior. The true advantage of using any type of heat pump is that you are taking advantage of the free thermal energy available in the outside environment. If the unit is located in a conditioned space (as required by our local codes), the energy in the air being used to heat the water has been provided by the heating system (at least in the heating season). You are effectively paying to heat the air that's being used to heat the water. The article mentioned a 10 degree drop in temperature across the heat pump, but then discounted that by saying that the cooling averages 2 degrees and is insignificant. The simple physics of the situation tell the story - it doesn't actually make energy sense to use conditioned air to drive the water heater. Stephen Mittendorf

I agree... just doing the math on BTUs used to produce DHW via heat pump you know the load on the conditioned space that you now have to make-up with your home heating system or in summer with your AC system... when this is taken into consideration it becomes more expensive to run than some of the other alternatives.

Another problem with this article is that the cost to install a heat pump water heater is $1000 more expensive than an electric water heater... the installation is the exactly the same so why the extra grand?

It's hard to write about installation costs; they are extremely variable. In generating these numbers, I used my own contracting experience, bids I've seen, and online information to come up with representative numbers. There does appear to be an installation cost premium for heat pump water heaters compared to electric water heaters. Some of this is driven by the need for condensate disposal (which in many cases involves a separate pump and a new 120V outlet). There's also a larger markup associated with the more expensive equipment.

I am currently renting an apartment with a heat pump water heater that is in the unconditioned garage.

I have had electric and natural gas tanks and a natural gas tank less system in the past. This is a 50 gallon tank. We are a 2 person household Showers average 5-7 minutes each.

This system is inadequate. Unless we set it to the high output (quick recovery) setting only one person can take a shower every 2 hours or the subsequent showers are lukewarm at best, and we have increased the tank temperature to 130 degrees to allow for more cold water mixing for the showers. With these changes is is adequate but I do not see any cost savings in my electric bill compared to other systems.

I would not buy one of these at this point in time and do not see that they are saving the environment.

As much as I hate to hear about bad experiences with green technology, I think it's important to share these and learn from them. It definitely sounds like something is wrong with the equipment or installation. The first possibilities that come to mind are a dirty air filter, low refrigerant, or possibly that the garage is too cold for effective heat pump operation. I think it would be worth asking your landlord to get a technician out to troubleshoot.