Eichlers Get an Upgrade

Performance improvements for the prized homes of an influential developer who wanted us all to be able to own one.

Eichler homes, once designed for California — mild climate and postwar optimism, are now being upgraded to meet modern energy and comfort standards. With their floor-to-ceiling windows, minimal insulation, and radiant floors, these homes offer both design charm and efficiency challenges. Architects like John Klopf are retrofitting them with new insulation, air-sealing, updated HVAC systems, and solar-ready roofs — carefully preserving their open layouts and iconic look.

A “Commitment to Practicality and Comfort”

The American Dream is an elusive proposition. If a common denominator can be found, it may be the possibility of homeownership. To this end, few captured the spirit of the dream better than West Coast developer Joseph Eichler. From 1949 to 1974, Eichler built over 11,000 homes, most of them in California’s Bay Area, that came to define the midcentury-modern and California-modern aesthetics. Livability was the key ingredient in an Eichler home.

The term evokes “informal and adaptable space, convenient for all residents, with an open disdain for the rules of elegant propriety,” wrote Gwendolyn Wright, a professor of architecture at Columbia University, in her foreword to the 2002 book Eichler: Modernism Rebuilds the American Dream. Wright continued: “No single architectural element embodied livability. It assumed a thorough and ongoing commitment to practicality and comfort throughout the dwelling.”

Developing the Hallmarks of California ModernBorn in New York City, Joseph Eichler (1900–1974) was the son of German Jewish immigrants. Beginning in the late 1940s, inspired by the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, Eichler set out to develop modest suburban homes that embodied bold, modern design and fully embraced California’s climate with their opening to the outdoors. Eichler not only set a new design standard for residential developers, but he also pioneered the practice of connecting merchant builders with some of the most respected architects of the era. Eichler was committed to undoing racist housing policies that prevented nonwhite people from purchasing a home in restricted subdevelopments. Over the better part of three decades, Eichler developed more than 11,000 tract homes in and around the San Francisco Bay Area, Sacramento, and Southern California. His homes came to define midcentury-modern and California-modern styles with signature details.

|

Making an Eichler More Efficient

That was then. As impressive as Eichler’s single-story prototypes were as both a design exercise and demonstration of community building, these homes are no longer attuned to present-day energy prices or homeowners’ expectations for comfort and health. Large single-pane windows, outdated boilers, and wall and roof assemblies with little to no insulation all translate to homes with “no energy efficiency whatsoever,” says John Klopf, a Bay Area architect.

Appropriately, there is a market for bringing Eichler homes up to or beyond California’s current building and energy codes. Klopf, whose practice has completed over 150 Eichler remodels to date—two of which are featured here—admits that Northern California’s climate was once well-suited to these houses, but not anymore.

“The climate is getting warmer,” he says, “and a lot of them now need air-conditioning and air-sealing. They’re tricky to remodel for energy efficiency.” This hasn’t stopped Klopf and others from taking on the challenge. The goal with such iconic homes is to complete the performance upgrades without losing the character and charm they are revered for.

Pebel Rodriguez Suero is an architect who has long loved Eichler homes. But as a certified passive house designer, she recalls the moment when she discovered just how inefficient they are. “I was heartbroken to learn just how terrible they are, environmentally speaking,” she says. “Even when you have [helpful] things like [solar] orientation and radiant flooring, these are irrelevant when your home is basically a shed.”

The typical Eichler home was made to foster connections to the outdoors, to blur the lines dividing one’s living space from the backyard. Big glass walls and doors and open-air atriums made this possible, while yielding an inefficient building enclosure.

Undeterred, Suero began thinking about how a typical Eichler could meet passive house standards. She created a list of considerations, starting with an energy audit and air-leakage tests and following up with air-sealing and insulation upgrades, new windows and doors, and balanced ventilation systems. She recommends making the most of the thermal mass Eichler homes are known for, adding PV systems, and using smart-home technologies to reduce and monitor energy use.

What might set Eichler homes apart from other historical homes undergoing similar renovations is the scale of the investment. Today the average three-bedroom, two-bath Eichler home, which rarely exceeds 2000 sq. ft., will go on the market for at least $3 million. On top of this steep price tag, the reality of Suero’s proposed upgrades will add considerable cost. Often she will look for ways to meet her clients in the middle. “I give them the numbers, the R-values, so they can see the difference,” she says. “Everyone wants the best that they can afford. People want to understand where their money is going.”

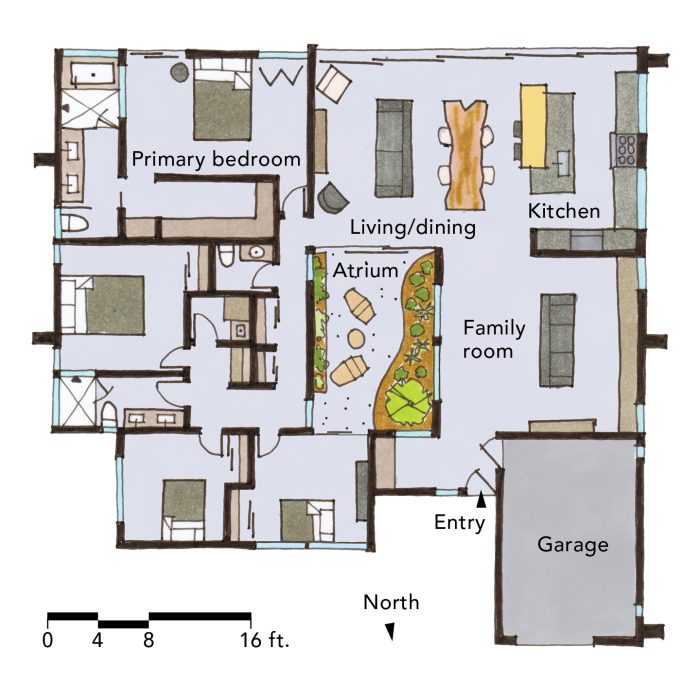

From Tangible to Treasured Built to be stylish yet egalitarian, Eichler homes often sell today for millions of dollars even when still needing performance upgrades. This Klopf project, the “Indoor-Outdoor Eichler,” is an example of owners willing to do the work. Cost aside, today’s options for big exterior doors align perfectly with Eichler’s goal of connecting interior and exterior. It’s not the most energy-efficient detail, but it represents a trade-off with insulation and air-sealing upgrades, and the installation of new, more efficient HVAC equipment. The floor plan had some modifications, but the overall Eichler style is intact with the high ceiling, great room, atrium garden, and outdoor connections, even in the bathrooms. |

Upgrades and Trade-Offs

In 2021, Klopf and his team completed a gut renovation of a 1928-sq.-ft. Eichler home in Palo Alto. The home, aptly dubbed the “Indoor-Outdoor Eichler,” was completely reconfigured from the inside out. This included insulating the roof and walls to achieve minimum benchmarks outlined by California’s building codes.

The roof was retrofit on the exterior with a combination of closed-cell polyurethane spray foam and rigid polyiso insulation and EPS depending on the location, achieving a minimum R-value of R-38. Insulating above the roof decking maintained the exposed framing and tongue-and-groove ceiling inside. The wall cavities were filled with fiberglass, meeting the minimum R-13.

The home’s footprint was slightly expanded in two places. In its original state, the house formed a blocky C-shape around an open-air atrium and the home’s main entry. One small addition created an enclosed entry that connects to the garage, while mostly preserving the atrium. The other addition is positioned lengthwise along the site’s eastern edge. About 240 sq. ft. of new space enlarged the primary bedroom and allowed space for an additional bathroom. For the additions, the new slab was insulated with 2-in.-thick rigid EPS boards and hydronic radiant-floor heating, which was an original system in many Eichler homes.

“We sealed everything in this home,” says Brian Smith, vice president and project manager with San Jose–based Starburst Construction. Smith says the biggest culprit in terms of inefficiency was the windows: “Those original single-pane Arcadia windows leaked like a sieve. That’s where you lose a ton of value, and most of the homes have very little wall space. They’re pretty much all glass.”

Insulated double-pane windows replaced all the existing windows. The fireplace and chimney were removed, and the roof was made solar-ready. More notably, the owners opted to add a multipanel sliding door that creates a 30-ft.-wide opening between the main living space and the back patio. Smith says the owners have no delusions about the fact that this luxury effectively “washes out” any energy efficiencies the house has otherwise achieved with the recent retrofit.

There are two kinds of Eichler clients, says Marissa Smith, Starburst’s CFO (and Brian’s wife). There’s the “traditional Eichler enthusiast” who wants to modernize things but maintain the home’s historic “essence.” Then there are those who love Eichler but want to “change the home for better energy efficiency and more storage.” These owners seem to be a combination of the two.

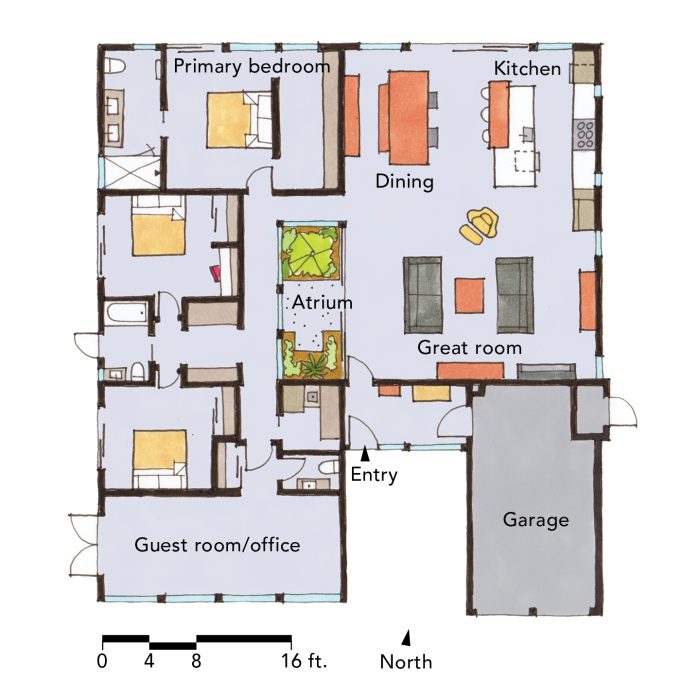

Once an Eichler, Still an Eichler Unless significant space or a second floor has been added, even an updated Eichler home is recognized easily with its low profile and flat and low-pitched rooflines, as is the case with Klopf Architecture’s “Great Room Eichler.” The energy upgrades here included new windows and doors, insulation and air-sealing, and updated HVAC equipment. As part of the remodel, the floor plan was also reconfigured for the current homeowners. Looking around the house today, however, you’ll still find all the characteristics that define an Eichler house, including large expanses of windows, exposed framing, a tongue-and-groove ceiling, and an interior open-air atrium. And it maintains its modest street-facing character. |

Expanding Opportunities

Of all the enduring features of an Eichler home, its radiant flooring is top of the list. In another Klopf project, a 1,684-sq.-ft. Eichler in Sunnyvale (the “Great Room Eichler”), a big upgrade was removing the water heater and boiler and replacing them with a high-efficiency, gas-fired, tankless water heater from Navien for both domestic hot water and radiant heat. An air-source heat pump conditions the living space. Given the prominent glazing, installing wall-mounted minisplit heads wasn’t an option. Instead, ceiling-mounted cassettes were located strategically.

Klopf says work such as this creates opportunities for other critical upgrades: “If you’re going to do that much work, it’s a great time to address other issues, like adding ceiling lighting, which most Eichlers don’t have.” And with the extended work of running cable and cutting holes in the roof decking for junction boxes and light fixtures, he feels like that presents a good opportunity to inspect the quality of the roof itself, run conduit for future PV, and add exterior insulation.

“The roof is the linchpin of these homes,” Klopf says, citing the original tar and gravel that adorned most Eichlers and that needs to be replaced on just about every retrofit project. “It’s not practical to drop the subceiling, because ceiling heights are already at just 8 ft., sometimes 10 ft. in the middle of the living room where the roof slopes. And you have a sheet of glass going all the way up to the wood decking, so the ceiling would dead-end into a window. So when replacing and insulating the roof, all that new thickness has to be added to the top.”

The Great Room Eichler has a C-shaped plan nearly identical to that of its Palo Alto kin. About two-thirds of the atrium was infilled to expand the home’s living room as well as create storage space that connected to the garage. This left a sliver of the atrium while “maintaining the look and feel of an Eichler home,” says Tiffany Truong, COO of Keycon, the project’s general contractor. An additional 265 sq. ft. of space was added for a new guest bedroom and home office.

When it comes to getting under the slab, replacing the roof, or even refurnishing the interior of an Eichler home, Truong says most of her company’s clients move in phases, based on what budgets allow. “Some parts of these homes were built to last,” she says, “but a sewer’s end of life is about 60 [years]. I’ve replaced a lot of them.”

Respecting Past and Future

My father lived in three different Eichler homes as a child. When I look at photos of him as a boy, with just portions of a facade from one home or another in the background, I feel like I’m catching glimpses of the idyllic American Dream at its finest, at least when considered through the lens of the suburban homestead.

I see homes that appear practical, modest in scale, and made to be used. Their massing and materials, to Gwendolyn Wright’s point, are anything but elegant. And yes, I see an era when the dream felt a little more accessible, at least financially speaking. Still, becoming overly nostalgic for this period would be ill-advised, and so the work of retrofitting these iconic homes for energy efficiency continues.

Designers such as Klopf and Suero have their work cut out for them, and they acknowledge what a financial undertaking it can be for homeowners. As with any houses past their prime, Eichler homes need upgrades. For their part, they present a distinct opportunity to bring together the best qualities of mid-20th-century design and 21st-century performance.

— Justin R. Wolf is a Maine-based writer who covers energy and climate policy and green building trends. Photos by Mariko Reed.

RELATED STORIES

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Code Check 10th Edition: An Illustrated Guide to Building a Safe House

All New Kitchen Ideas that Work

Pretty Good House