How Lumber is Produced

From forest to framing, learn about the process of transforming timber into lumber and the importance of sustainable forestry.

I have a friend who owns forests, and he invited me to see how timberland produces lumber. As a former carpenter, I felt it was high time to learn where the raw materials of my trade came from and how trees were converted into 2x4s. A quick estimate on my calculator suggests that I am responsible for consuming about 1,400 acres of forest during my 40 years as a home builder. I jumped at the chance to learn firsthand about the entire cycle of this consumption.

The Canadian company West Fraser is the largest softwood supplier in the world and the third largest in the United States, behind Weyerhaeuser and Georgia Pacific. It owns the Angelina lumber mill, a state-of-the-art facility near Lufkin, Texas, which is two hours north of Houston. My friend arranged for me to tour the facility with Wiley Quarles, the general manager, and two silviculturists from American Forest Management.

Silviculture and forest sustainability

Silviculture comes from the Latin silvi (forest) and culture (growing). As with agriculture, which is all about producing food (and lots of it), those cultivating timber seek to conserve and improve the quality and yield of their forest stands. I first heard about silviculture and the technical sophistication of sustainable forest cultivation from Willie Newman, who talks about longleaf pine with the passion of a wine connoisseur, and his aide-de-camp, Andrew Boughton.

With nearly six million acres of forest under management, four million of which are certified under Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) sustainability standards, Newman tells me, “We operate the same way, whether certified or not; we follow best practices on every stand, so we don’t have to worry about it.”

Some landowners want the timber certified, while others do not. The difference between certified and conventional lumber comes with reporting and chain-of-custody tracking, Newman explains; similar to building houses under a green certification, such as LEED, a little bureaucracy is needed to get the label. Still, responsible builders follow best practices even without a certificate to prove it. And American Forest Management operates all their timberlands under SFI guidelines or better because, as Newman puts it, “Why do anything but the right thing?”

Nonetheless, it looks terrible if you have come across a timber stand after harvest—colloquially known as clear-cutting. In truth, harvesting entails removing specific trees that have obtained desired stature and girth after a 23- to 30-year growth cycle. Careful separations and limits exist between harvested areas to protect the forest ecosystem, with 50-foot riparian buffers—which contain trees, shrubs, and other natural vegetation—along streams and other biologically sensitive areas remaining untouched.

After the harvest, the forest looks dead to a layperson’s eye. But that’s when the cycle begins again, and this is what makes lumber a renewable resource. “It looks bad because we leave the tree slash behind to serve as a biological silt fence, protecting streams, so the water stays clear, and to provide habitat for small animals like opossums and field mice,” says Newman, pointing out that these elements are essential best practices in forestry and carbon sequestration. Silt fencing mitigates runoff and prevents silt, or fine mud, from getting into these water sources. You can buy synthetic silt fences, but in this case, the tree slash itself does this work.

For one year following the harvest, the forest floor lies fallow while the weevil beetle makes fast work of the pine straw left behind. Attracted by the odor of freshly cut pine stumps, weevils nest in root bark, where their larvae hatch, feeding until they fly off as adults to another cutover to do it all over again. Since the hungry, growing beetles would consume any seedlings, the most practical and inexpensive control method is to delay planting for six to nine months after harvest.

According to the forestry industry, three-quarters of all the trees sowed last year were planted by forest products companies and private timberland owners. The forestry business is about growing and harvesting trees, so reforestation is important to the industry as it guarantees viability and longevity.

You may have noticed that the lumber you use today has improved dramatically from the 2x4s you nailed up 20 years ago—it’s much straighter, cleaner, and with fewer knots. When I was framing houses in the 1980s, we had a stage called “plumb and line” that entailed coaxing the walls into shape, cutting banana studs, splicing them back together into a straight line, and otherwise fixing the many defects inherent in conventional lumber. Over the last decades, forestry companies have selected pollen from the straightest trees with the least taper and the fewest burls. By selectively pollinating these trees and over generations improving the genetics, today’s forests yield better lumber—not as good as old growth, but better than what we had when I was holding a hammer 40 years ago.

Longleaf pine trees

After the weevils have moved on, foresters replant trees with improved genetics in containers with fertilizer to give the young sprigs a fighting chance. Timberlands are not irrigated, so trees are at the mercy of the climate. One species has better odds. Before European settlement, the longleaf pine savanna covered over 91 million acres in the southern United States into the early 1900s. Today, there are barely 4 million acres of this endemic tree, less than 6% of the original canopy. The conversion from natural forests to commercial pine plantations and policies focused on fire suppression led to the depletion of the longleaf pine. Slowly, the trend is reversing as owners discover the benefits of this species, which is well adapted to the local climate and resilient to the future impacts of climate change. The longleaf tolerates drought and rainfall variability so that it can take a dry spell or a soaking. It has a high fire tolerance, withstands high winds, and, when mature, resists beetle infestation.

A well-managed stand of longleaf pine grows to 4 feet in a year, shooting up through the meadow grasses. “During the grass stage of the tree’s life, its long needles close around the terminal bud to protect it from brushfire,” explains Newman. Native Americans used to conduct prescribed burns to stimulate longleaf’s growth, and now foresters do the same. The longleaf thrives with frequent, low-intensity fires that prevent fire-intolerant species from developing, control invasive plants, and stimulate seed production as the longleaf pine cone opens when heated. Next year, longleaf planting will replace the stand of loblolly pine shown in this article in the harvest photos.

After planting, the trees grow for 12 to 15 years before they are thinned. Trees compete for light, soil moisture, and nutrients. An overly dense stand stunts the growth of all trees, and the weaker ones die. Their death breeds disease, so foresters remove unhealthy, stunted, and malformed trees to allow the successful ones to grow. Foresters sometimes remove every fifth row of trees to allow room for equipment to roll in and conduct management operations. The trees removed become pulpwood used for products like toilet paper and OSB.

A second thinning occurs five to seven years later. Newman tells me that this second thinning includes pruning midspan branches, which allows songbirds and the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker to fly through the forest under the canopy, avoiding predators like pigeon hawks. This pruning also increases wood yield free of knots and blemishes. Newman says they collect and set aside fallen branches and logs to create brush piles that birds and other wildlife can use to breed and take cover in during extreme temperatures and severe weather—again, following SFI best-practice standards for forest management.

Once the trees reach maturity, an experienced forester inventories them and marks the boundaries of stands sold for timber. Then the loggers come. Using a “feller buncher,” a driver called a “shear hand” cuts and drops the trees. Skidder operators use a grappling arm to drag them out of the thicket to the landing area, where the loader operator pulls the logs through a “gate delimber” to break off the branches. He then eyeballs the trunks, categorizing them by size, and sorts and loads them onto waiting trucks. The trucks haul the logs to the lumber mill.

Species in the building codes

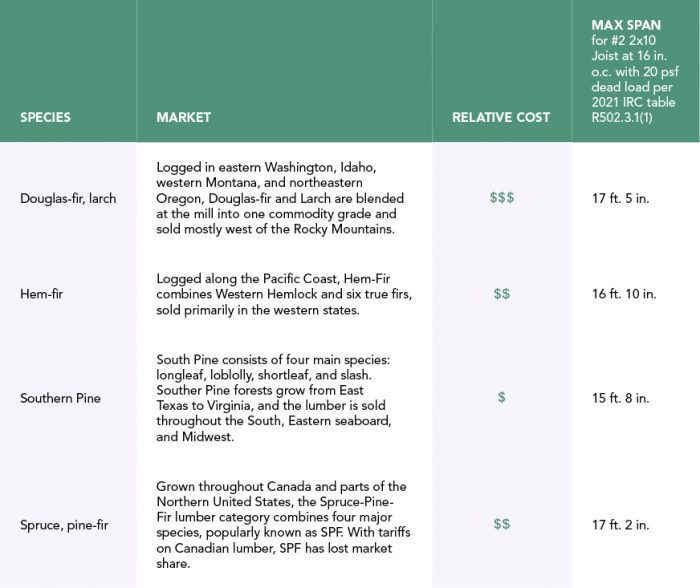

Suppose you thumb through your copy of the International Residential Code. The span tables reference six generic wood species in four categories: Douglas fir and larch, hem-fir, southern pine, and spruce-pine-fir. Although labeled as “species” in the code, they are generic names or categories encompassing about 40 species, broken down into four common structural characteristics. For example, white and black spruce represent two species, but for the sawmill and construction site, they both fit under the code category and strength characteristics of spruce-pine-fir.

Depending on where you build, certain generic species will dominate the local lumber market—for example, Douglas fir along the West Coast and southern pine in the South and Midwest. Traditionally, most of our construction timbers came from the western states. Oregon remains the largest single source, with an annual output of 5.2 billion board feet, or about 16% of the U.S. lumber market. However, the South has overtaken the West in total production. From the 521 million acres of productive timberlands in the United States, 40% is in the southern “wood basket,” producing about 61% of the lumber that supplies our construction sites.

The table breaks down the IRC lumber categories by market, strength, and relative cost.

At the mill

When the trees arrive at the mill, another loader operator removes the trees from the trucks, inspects the load, and sorts the piles according to size. A forklift with a grasping attachment picks up logs and feeds them into the mill. The first step in milling entails debarking. This process happens within the chamber of a huge machine resembling the belly of a locomotive that shakes ferociously as logs are drawn into what looks like a jet engine, where rotating rings scrape and strip the logs clean at a rate of 10 per minute. The ground-up bark is separated and stored in hoppers, where trucks line up to load and transport it to market as garden mulch. The naked logs roll onto a conveyor for processing.

From there on, high technology takes over. Laser scanners evaluate the raw logs for maximum cut value—starting with their length and girth and analyzing their highest use potential as dimensional lumber. A conveyor takes the undressed logs to a gang of circular sawblades that cut the logs to optimum length. The 5-in. and smaller logs become “chip-n-saw,” which yields pulpwood and 2x4s. They call it chip-n-saw because these skinny logs are stripped of their curved outer edges or “wane” with a chipping edger to create a block. The feathery material whittled off the trunks is conveyed to a screening area, where the chips are sorted by size to become biofuel, OSB, pellets, coffee sleeves, magazines, and other downstream uses. The remaining core is slabbed and sawn to create 2x4s and other small-dimension lumber. The larger, 7-inch-and-up “sawlogs” may yield beams, posts, and more 2x4s. The whole system runs at an astonishing 125 boards per minute.

Conveyor belts send the random-length boards to be cut into standard lengths, such as 8, 10, 12, 16, and 18 feet. Then specialized conveyors unscramble the boards and drop them into huge sorting bins resembling gun magazines. As the magazine capacity reaches the desired number of pieces, the machines lower and drop their load onto a deck for bunking and banding. The next stop is the kiln.

Kilns use electric heat generated by sawdust-burning boilers to desiccate the lumber to a prescribed moisture content. The weight of a fresh-cut tree is about 50% water, and the kilns extract enough liquid to supply the local water company with nearly 10,000 gallons of tap water daily. All of it is filtered, tested, and potable. Afterward, the boards return to the mill for planing, whereby a 2-inch by 4-inch plank becomes a 1-1/2-in. by 3-1/2-in. length of clean, white, smoothly finished 2×4.

Before loading the lumber onto waiting trucks, the last step involves grading and stamping. This used to be the job of skilled lumber graders. Now it’s accomplished with an ultra-high-resolution scanner that collects information on all four faces of each board and conveys it to analytical software for high-speed grading and stamping. Once the lumber is banded and loaded, the trucks move the material through the wholesale chain to your local supplier and ultimately to your job site for its final resting place in a wall. Each tree yields about 22 2x4s. An average house consumes about 100 trees—stop and think about that.

Home building and cooking have a lot in common. We have the agricultural industry to thank for our food and silviculturists for our renewable sources of lumber. If you say grace before a meal, consider thanking the forest and the many hands that brought that wood to your job site before firing the first nail of the day.

Photos by the author.

RELATED STORIES

View Comments

Great article Fernando! Loads of details in the process I wasn't aware of.

Thank you, Mike, I greatly appreciate your comment.