Why I Work Wood

Great moments in building history: Work makes you free

In 1958, our next-door neighbors, the Sterbas, had their second baby in two years, and Mr. Sterba decided to add a second story to their home. One morning in mid-June, trucks from the lumberyard delivered piles of plywood, bundles of 2x4s and stacks of joists and rafters.

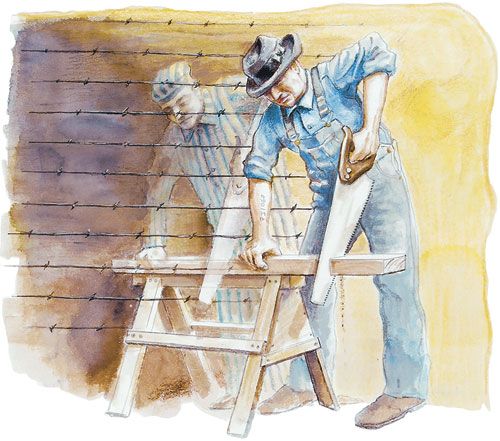

I was 8 or 9 then. Our neighborhood was bereft of kids my age, and the freedom of summer vacation was beginning to drag when I noticed that Mr. Sterba and an elderly gentleman had begun cutting and hammering pieces of wood into frames for exterior walls. I moved closer and watched until Mr. Sterba asked me for a framing square near where I was standing. It was a test of sorts. I knew what a square was, and from then on I was in. I hung around each day and toted boards, swept sawdust and got underfoot, but both men were tolerant of a curious kid.

The Sterbas worked exclusively with hand tools, a fact I found unremarkable except in hindsight. It soon became apparent who directed whom. The old man taught us both. Measuring, cutting, squaring and hammering, he worked slowly, unhurriedly and beautifully, each cut, each paring shave of the chisel a masterpiece of economy, power and judgment. Each night as I swept up, he sharpened each tool, filing the teeth of the two saws, stroking the chisels on the oilstone and then doing the same with the plane iron from the long jointer plane.

After a couple of weeks, the house was framed and sheathed in plywood, the roof was shingled, and Mr. Sterba returned to his job, leaving the old man and an enthusiastic kid to finish the house.

I had talked to my father and mother about the construction next door; of course, they knew more than I about the Sterbas’ situation. The old man, who didn’t speak English, had escaped Czechoslovakia just before the Soviets stormed in, and he’d had a number of other adventures. I had rather taken him for granted. Young Mr. Sterba cut a much more dramatic figure; he’d been to Korea and fought the Commies while the old man just looked kind of dilapidated. But after hearing he’d escaped the Soviet peril, I imagined a more glorious background for old Mr. Sterba, and I began to pay him closer attention.

He emerged from the basement early each day, drinking tea and watching the sunrise. I knew this because I got up at 5 o’clock one morning just to check on what he did. He always wore a ratty old jacket, a light blue work shirt, overalls and a tattered hat. By the time I’d arrive, he’d have been working for a couple of hours, and he’d have laid his jacket aside, neatly folded. As the morning grew warm, he’d roll up his sleeves. It was then that I noticed his tattoo, a number on his arm, and I worked beside him for several days before I pointed to it and asked what it meant. He paused, then just sat back on a sawhorse and looked at me for a long time. I thought I’d asked the wrong question and began to feel apprehensive. It became clear from his manner, however, that the question was okay, but that I’d asked something important. He looked at me intensely, then said, “Arbeit macht frei, arbeit macht frei,” a phrase that meant nothing to me. He tried several more times, but I didn’t understand, and eventually we just went back to work.

The phrase stuck with me, and I repeated it to my father, who spoke Czech. “Our bite mocked fry,” I said to my dad, but he didn’t know what it meant either. I puzzled over it all summer, but eventually concentrated on the more immediate pleasure of working with a fine craftsman. At the end of the summer, I had to return to school. On the Friday before school began, the Sterbas had a small surprise for me. They laid several packages on the sawhorse at the end of the day, and when I unwrapped them, I found three Stanley chisels, a boy-size handsaw and a hammer.

The weight of school and seeing friends I hadn’t seen for much of summer kept me from the house next door, and I didn’t keep that easy relationship with the Sterbas that I’d had that summer. Old Mr. Sterba moved on after Thanksgiving; he had other children on the West Coast, and that summer moved into the past, to be re-examined only when I built something with the tools they’d given me or when I’d think of that tattoo. What had Mr. Sterba meant?

I know now what Mr. Sterba meant, at least literally. I took German in high school to get in touch with my Teutonic roots and learned the phrase meant “Work makes you free,” a simple, harmless phrase until I learned how it was used. Still, I don’t know what Mr. Sterba meant. Did he think I’d recognize that phrase as the mocking motto of Dachau, where this freedom was synonymous with death? Or did he truly mean that the dignity of work allows one to transcend even the absolute evil of Dachau? I don’t know for sure, but as I remember his strong, capable hands pushing his chisel through the wood as it unerringly followed the line, I do know that he lived his life, at least for that summer, as if that last meaning were true, and now so do I. And that’s why I work wood.

—Andrew Schultz, Lincoln, Nebraska

Drawing by: Jim Meehan

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Affordable IR Camera

Reliable Crimp Connectors

8067 All-Weather Flashing Tape