The Rise of the Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU)

Backyard cottages and laneway houses have become increasingly popular in the Pacific Northwest. Will they work in your neighborhood?

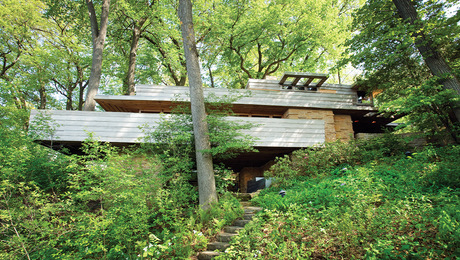

Synopsis: The Pacific Northwest is the center of a growing movement to allow auxiliary residences no larger than 800 sq. ft. to be built on lots with existing homes. These residences, known as accessory dwelling units (ADUs), include new, detached dwellings; converted garages; basement apartments; additions; and apartments carved out of an existing floor plan. In this article, contributing editor Sean Groom gives a brief history of the ADU movement, explains why ADUs are becoming popular but also how they’re misunderstood, and describes the multiple benefits of the growth of ADUs. These benefits include increasing the amount of affordable housing without the need for government funding; limiting sprawl; creating multigenerational living spaces; and enhancing energy efficiency. In four separate sidebars, Groom writes about the ins and outs of financing an ADU; profiles a former finish carpenter in Vancouver, B.C., who started an entire business in building ADUs; and describes two very different ADUs: a backyard building that contains a home office and a guest room, and a 637-sq.-ft. two-bedroom cottage for guests that doubles as a painting space and a workshop. See more award-winning homes from the 2013 HOUSES Awards.

Portland, Ore., known for its drizzly winters, coffeehouse culture, and craft beer, also has made a name for itself with innovative zoning regulations. More than 30 years ago, as an antisprawl measure, the county drew a ring around the city to define the limit of development. Since 2009, Portland’s zoning regulations have made the city a hotbed of ADUs.

ADU is shorthand in housing-policy circles for accessory dwelling unit — which the rest of us might call an in-law apartment, a laneway house, a granny flat, a carriage house, or a backyard cottage. An ADU is not a duplex, which typically has identical or similarly sized units. Instead, it’s an auxiliary home of less than 800 sq. ft. It can be a new, detached dwelling; a converted garage; a basement apartment; an addition; or an apartment carved out of an existing floor plan. ADUs are not a new idea. Wander through an old city neighborhood with a careful eye, and you’ll find carriage houses, apartments above garages, servants’ quarters converted to apartments, and English basement apartments.

These types of housing are enjoying a renaissance for reasons both old and new. From a public-policy standpoint, ADU friendly zoning regulations are attractive to local governments because they promote affordable housing without government funding, encourage dense development, reduce carbon emissions, and stimulate local construction jobs. At the household level, ADU-friendly zoning means more affordable housing, flexible space that changes with the family, rental income, multigenerational housing, and space to age in place.

An urban-policy tool

The ADU movement began about 10 years ago when Santa Cruz, Calif., revised its zoning regulations to allow ADUs on most single family lots in town in an effort to address an affordable-housing crunch. The housing bubble of the 2000s was inflated in Santa Cruz, an oceanside university town within commuting distance of Silicon Valley. By 2002, the median home price was so steep — more than $500,000 — that over 50% of the population rented and the vacancy rate had dropped below 2%. The city found affordable-housing programs costly to administer, and pressure in the rental market meant that rents were high. The city embraced ADUs because they functioned as a homeowner-funded affordable-housing program while providing regulation for a cottage industry in illegal garage apartments.

The idea is that the rental income from an ADU (or the main house) helps to make a house more affordable. By providing small, nice apartments at reasonable rents in single-family neighborhoods where there wouldn’t typically be rental opportunities, renters gain a yard, more privacy, a quieter environment, less traffic, and access to schools they typically couldn’t enroll their children in.

Portland’s commitment to limiting sprawl and increasing housing density makes ADUs a natural fit. When the city adopted new ADU regulations in 2009, there were suddenly 148,000 new potential lots in the city that could increase housing density without the need to build vertically. Neighborhoods can retain their character, and building in the backyards of established neighborhoods reduces the demand for expensive new infrastructure. It’s a component of “passive design” — using location to conserve resources. By focusing development in walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods with access to mass transit, the city reduces the number of car trips and pollution.

For more photos and details, click the View PDF button below: