How it Works: Household Electricity

Electrician Cliff Popejoy explains the systems and components that bring power from it's source into and around your home.

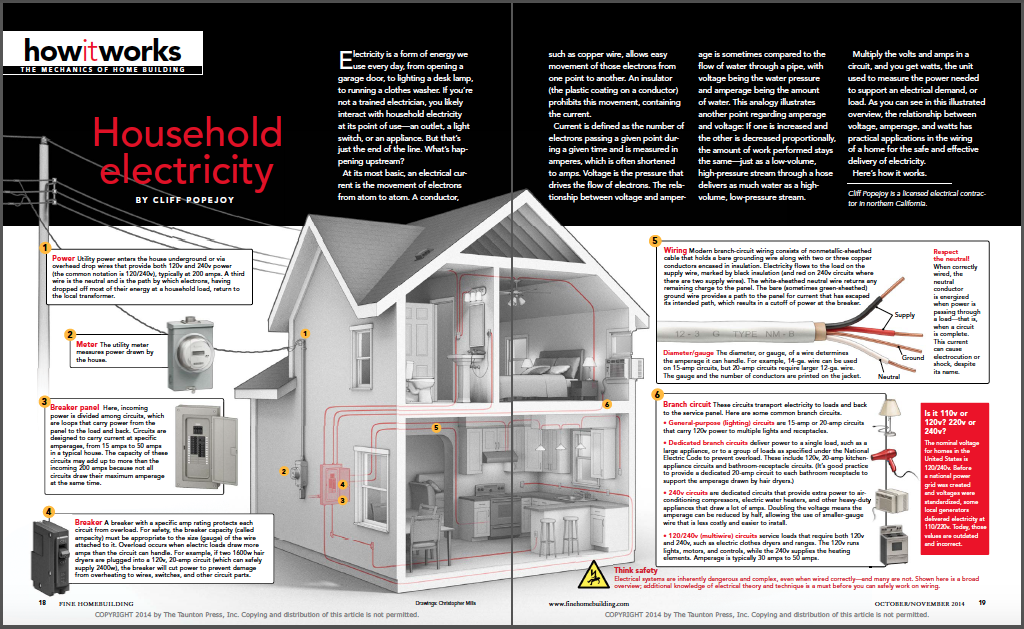

Synopsis: In this issue’s “How It Works,” licensed electrician Cliff Popejoy explains the ins and outs of household electricity. Using an illustration of a typical house, Popejoy begins where electrical power enters from the overhead drop wires and proceeds through the meter to the breaker panel and then throughout the house via branch-circuit wiring. He discusses wiring and identifies the purposes of each of the conductors housed in nonmetallic-sheathed cable. He then describes four common branch circuits: general purpose circuits, dedicated branch circuits, 240v circuits, and 120/240v circuits. Along the way, he also explains the relationship between amperes and volts.

Electricity is a form of energy we use every day, from opening a garage door, to lighting a desk lamp, to running a clothes washer. If you’re not a trained electrician, you likely interact with household electricity at its point of use—an outlet, a light switch, or an appliance. But that’s just the end of the line. What’s happening upstream? At its most basic, an electrical current is the movement of electrons from atom to atom. A conductor, such as copper wire, allows easy movement of those electrons from one point to another. An insulator (the plastic coating on a conductor) prohibits this movement, containing the current.

Current is defined as the number of electrons passing a given point during a given time and is measured in amperes, which is often shortened to amps. Voltage is the pressure that drives the flow of electrons. The relationship between voltage and amperage is sometimes compared to the flow of water through a pipe, with voltage being the water pressure and amperage being the amount of water. This analogy illustrates another point regarding amperage and voltage: If one is increased and the other is decreased proportionally, the amount of work performed stays the same—just as a low-volume, high-pressure stream through a hose delivers as much water as a high volume, low-pressure stream.

Multiply the volts and amps in a circuit, and you get watts, the unit used to measure the power needed to support an electrical demand, or load. As you can see in this illustrated overview, the relationship between voltage, amperage, and watts has practical applications in the wiring of a home for the safe and effective delivery of electricity.

For a diagram and breakdown on how household electricity flows, click the View PDF button below.

For a diagram and breakdown on how household electricity flows, click the View PDF button below.

From Fine Homebuilding #246