Modern Techniques Restore a Historic House

There's no point in living in the past, so use these techniques to bring an old structure into the present

A complication of trim The paneled embrasure that angles away from the room and its attendant casing would fill any carpenter’s day, now or back then. The biggest departure for a modern trim carpenter restoring an 18th-century home is the order of construction: The trim goes on before the plaster. This allows the casings, referred to collectively as the architrave, to be slightly recessed in the plaster, which in turn helps to seal out drafts.

Montpelier, the home of President James Madison, has gone through several architectural incarnations, but it started out as a no-nonsense brick Georgian built on the Virginia frontier in 1760. Iron nails were costly in those days, and carpenters used surprisingly few of them. They relied instead on complex joinery that seems onerous by today’s standards, such as dovetailing a casing leg to a plinth block. In the spirit of restoring the house to its Madison-era state, my crew has helped to duplicate every one of the details, down to the last notch.

We didn’t use bowsaws or a brace and bit. In particular, project manager and former boatwright Bill Bichell came up with a succession of timesaving tricks that employed modern tools to make the work efficient. The first-floor front windows are a good example. The 17-in.-thick walls are punctuated with recessed window openings called embrasures, which are made of paneled jambs splayed at an angle to maximize the passage of sunlight. Taking our cue from an existing window we assembled each embrasure on site.

We began installation by cutting the jambs to length and temporarily fitting them in position. The legs were cut shy of the floor for an easy fit; a thin baseboard, called the running plinth, covered the gap later. The final step in the process was to measure the width of the frame and panel that goes below the window.

The architrave’s outboard edges were nailed to wooden plugs in the brickwork, and the inboard edges were nailed to the jambs. Finishing up included drawing the backbands tight, fitting the running plinth, and pinning the decorative bead into its dado.

A positive lock instead of fasteners

An angled tongue milled on the edge of the paneled jamb engages a groove plowed in the face of the window frame and makes alignment of the long pieces easier.

Minimize scribing in thick stock

Like much of the trim used in the house, sturdy plinth blocks were made of heart pine. To make scribing the plinths to the floor an easier process, carpenters routed a shallow pass from the plinth’s underside, knocking off high spots with a chisel. As seen above, among the unusual details we reproduced were casings dovetailed into the backs of the plinth blocks.

A lesson from the boatyard

For accurate measurement of the width of the lower panel between the jambs, project manager Bill Bichell used a simple trick: He slid two thin wood scraps outward until they contacted the jambs, then clamped them together. The measurement is transferred to the corresponding part of the panel.

Trick of the trade

To minimize hammer marks on the trim, use a scrap of hardboard slotted for the protruding nail. The hole at the other end makes the guard easy to hold.A curious detail creates the need for a jig

The delicate bead that divides the upper and lower halves of the leg jambs was presumably intended to make these fixed pieces mimic the folding window shutters found on costlier embrasures of the period. The dado that housed the bead also had to include a thicker bullnose panel cap. To rout the dual-width dado, Bill Bichell devised a straightedge router jig featuring a stop attached with rare-earth magnets. He routs the short, wider portion of the dado with the stop in place, then changes to a smaller-diameter bit, quickly removes the stop, and completes the dado.

|

|

Clean, accurate, and complex miters

The head of the architrave meets the legs in a hip miter, a joint more difficult to cut than a plain miter but also less susceptible to seasonal humidity changes. Hip miters are marked out on the flat back side of the trim and are rough-cut with a jigsaw (1). A hardboard straightedge is clamped to the trim; then a router with a 1/2-in. straight bit cuts to the line (2). A sharp chisel cleans up the intersection of the two cuts (3).

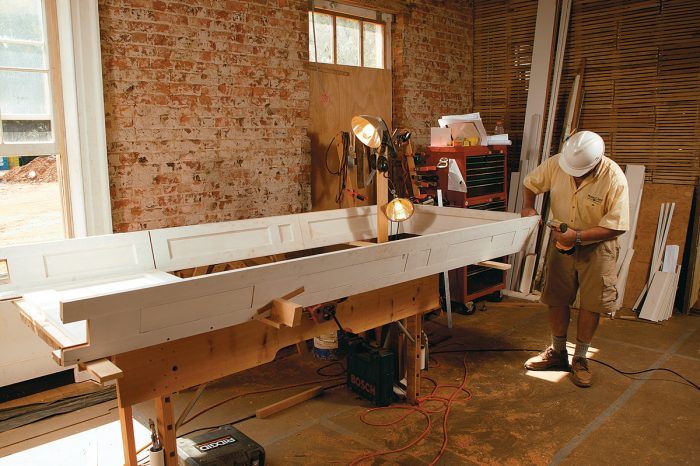

Blocking captures the angle on the bench

The finished parts are assembled as a unit on the bench prior to installation. Placed near the midsection, blocks support the jambs at the appropriate angle; shims keep everything tight.