“Someone someday will track the roots of modern human loneliness to a loss of intimacy with place, to our many breaks with the physical earth. We long for a specific place, a certain geography that gives us a sense of well-being. I strive, when I travel, to meet the land as if it were a person. I wait and wait for it to speak.” Barry Lopez

Carole King sang: “Doesn’t anybody stay in one place anymore?” It does amaze me at times to see that we Americans are so restless, always on the move. Maybe it is like John Muir said: “The world is huge. I want to have a good look at it before it gets dark.”

Sometimes I wonder where it comes from, this restlessness. Like an old prospector, we seem to know that the “mother lode” is just over the next hill. One more grubstake and happiness will be found. So from the covered wagon heading west to our automobiles heading is all directions, we are often people “on the go.” Like the pioneers, we can load all we want, labeled and tied in boxes and bundles, in a U-Haul, fold our tent and move on.

The sad part is that what we lose when we move is not stuff, but our sense of place and often, close contact with our children and their children. I know I miss that. My prairie home nurtured me and let me know who I am in a way that 50 years of city living could never do.

In 1942, when I was eleven, we moved about 100 miles further north to another isolated rural village, Harrison, pop. 500. This town was not far from the borders of Wyoming and South Dakota and from what was left of the great Lakota nation. These Native Americans had been removed from their beloved Black Hills to the desolate land called the Pine Ridge Reservation. My father had another job working on a New Deal agriculture program that paid a bit more, but still less than $100 per month. My parents had lost their house in Harrisburg because they were unable to repay a loan on money, $600, borrowed from the bank to pay for my oldest sister’s appendectomy. Sounds familiar, no? From then on until their deaths, except for a couple of years in Montana, they were renters.

It was here in this cattle raising outpost that I was introduced to the pre-cut house. The house I worked on was ordered through the Sears mail order catalog. The house was then pre-cut in a factory, sent by railroad to the new owner, brought to the job site, and assembled piece by piece. You can still order these houses today even though their popularity waned radically post World War II. Different styles, bungalow stick frame, timber frame, and log cabins are all available. In today’s version, a set of plans can be programmed into a computer which will instruct automated machinery how to cut all the house parts and even to nail together sections of wall. This approach has value today especially for the owner who wants to save money by being the builder, but who does not have extensive knowledge of how a house goes together. Further, factory cut houses should insure that quality wood is being used and that there is less waste. When these houses are delivered in panels, they go up fast allowing them to be closed in from the weather rather rapidly.

In 1948 when I was 17, I was working for a country ranch family who had decided to build a “pre-cut house” for a brother and his family. Up until WWII, thousands and thousands of pre-cut houses were built throughout our country and Canada. These houses were offered in many different models through mail order catalogs some costing as little as $1000.

The pre-cut house, sometimes called a kit house, was just that. Like a set of Lego, it came with all parts cut to size at the factory, packaged, and labeled along with blueprints and many pages of instructions on how to put everything together. These bundles included siding and shingles along with kegs of nails, hinges, and other hardware. Nails in those days came in kegs, a small, slatted, wooden barrel held together with iron bands, containing 100 pounds. Plumbing and electrical parts were available, but had to be bought separately.

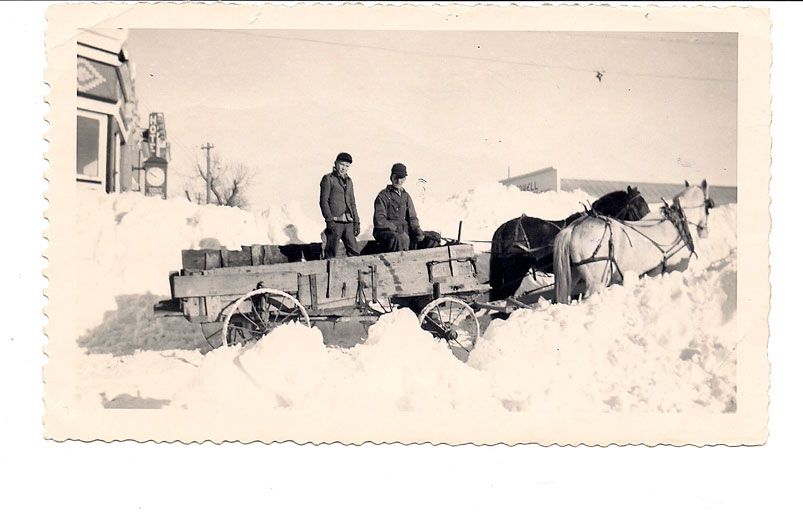

The pre-cut house arrived in two rail cars set on a siding at the local train depot. From there it was brought, package by package, to the site with a team and wagon operated locally by Captain John and his son Dee. This is the way the Captain earned his livelihood, carting coal from a railroad car to houses for peoples’ stoves, bringing food to the house bound, and doing general hauling and cleanup around town.

The master carpenter, Adolph Eisler, hired to put all the pieces of this house together was an immigrant from Germany who homesteaded in the county. One of the stories he told was about his first job when he arrived in New York in the 1800s. He found a job helping to make pianos working for 5 cents and hour. Beer, he said, could be bought for 5 cents a mug. An hour of work bought a mug of beer!

Adolph was my teacher. He came to the job site with his toolbox full of hammers, handsaws, chisels, and wood planes of various sizes that had been handed down to him from his own father. All of his tools, brought over from the “old country,” were well oiled, razor sharp, and wrapped in soft cloth to protect them from rust. I could tell that they were sacred to him from the way he used them with utmost care and precision. I was his helper, his apprentice, learning the names of all the tools and all the house parts, bringing them to him as work progressed. What a gift to me. I didn’t do a lot of nailing, but the knowledge and work ethic I learned from this patient man is still firmly with me today.

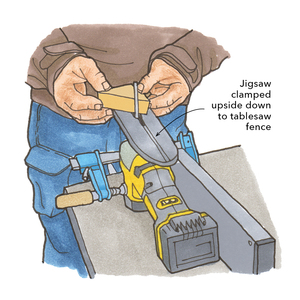

Step by step, we put all the parts together to frame the house. The bottom plate went down on the foundation. Floor joists and rim joists were nailed in place and sheathed with 1x stock. Now and then it was my job to cut a board that didn’t quite fit. Walls with their plates, studs, and headers were assembled leaving space for door and window openings. More joists and rafters formed the ceiling and the roof which was sheathed and readied for shingles. What a joy to see this whole house rise from the ground. At the end of the day I could stand back and silently say: I helped to do this. It really is a pleasure to be able to work and create with your own hands. I felt like an artist.

The roof too was sheathed with 1x stock and nailed to the rafters. Once the tarpaper was down, we began covering the roof with cedar shingles. It was here, armed with a shingling hatchet and a cloth apron full of small nails, that I was allowed to do some nailing. The hatchet part was used to split a shingle to width when you came to the edge of the building. The hammer part of the hatchet was used to drive the nails. I wasn’t fast, but Adolph said my work looked good. The old master encouraging his helper.

I close this chapter with a poem about, what else, the wind. It has been helpful to me on my journey.

“The wind, one brilliant day, called

To my soul with an odor of jasmine.

In return for the odor of my jasmine,

I’d like all the odor of your roses.

I have no roses. All the flowers

In my garden are dead.

Well then I’ll take the withered petals,

And the yellow leaves, and the waters of the fountain.

The wind left….and I wept, and I said to myself,

What have you done with the garden that was entrusted to you?”

Antonio Machado

Translated by Robert Bly

Read more of My Story As told By Houses:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

8067 All-Weather Flashing Tape

Handy Heat Gun

Reliable Crimp Connectors

View Comments

I find the history of these prefab homes fascinating.

This is a story well told.

Many a dream is to own one of theses homes built long ago.

Did the satellite dish come with the kit? :)

Bill 117,

Glad you spotted the satellite dish. I had other photos to choose from, but liked the way this house had been maintained so well. Larry Haun

Larry, I love it. I have a picture of a farm I used to summer on, the barn is collapsed and the house is empty and there is a huge old style satellite dish in the yard.

I loved the story. I know of a Sears prefab in Boston. It is said to be the first, I don't know.

Bill