The internet is abuzz with tiny houses. Everyone from Treehugger.com to The New Yorker is covering this trend. There’s a documentary–TINY: A story about small living–available on DVD and on Netflix and other on-demand services. And there’s a television show, too, on the FYI network. If you’re interested in our take on the matter, we’re planning to cover the tiny-house phenomenon in Fine Homebuilding‘s annual HOUSES issue this spring.

In that same issue, we’ll also feature the latest winner of our Best Small Home award, an award we give every year. To avoid spoiling the surprise, let’s just say that while this year’s winning home is very small, it may be too big to qualify as a tiny house–as would the 1600-sq.-ft. house that won last year or the two 800-sq.-ft. winners from 2013 and 2012. To many, though, these homes would be considerably tight quarters.

Small homes have long been at the heart of Taunton’s design content in our magazines, books, videos, and websites–and small homes are personal for me. I live in an approximately 800-sq.-ft. home with my wife and teenage son. Sometimes our house feels too big, sometimes it feels tiny, but mostly it feels just right, because I have tweaked the floor plan and we have arranged the spaces to suit our lifestyle. I don’t think I’d ever want a bigger home. In fact, I imagine that someday when my son is on his own, my wife and I could manage with less space, assuming that it is designed well.

That idea–that thoughtful design is more important than size–is the mantra we’ve been chanting in our small-home coverage for decades. And that’s the point Sarah Susanka reiterated in an essay in last year’s HOUSES issue. Despite being credited by Wikipedia with “starting the recent countermovement toward smaller houses when she published The Not So Big House,” Sarah’s focus is actually smart design. A smaller house is often a by-product of that process, but not the motivation.

Curiously, the Wikipedia page on tiny houses treats small houses and tiny houses as one concept. And though many of the benefits of tiny houses hold true of small houses, at least when compared to more average-size homes, it seems there is a conceptual difference between the two. Please excuse me for being a bit tongue-in-cheek as I suggest that small(er) homes, appropriately designed and scaled for the owners, have a lot to teach the home-design and construction industries, while tiny houses represent a fringe movement that can teach us about the value of lifestyle and its relationship to home but that is unlikely to impact our industry at large.

Small is relative

Almost a decade ago, when the housing market crashed, rumors started to circulate about what our homes would look like after the recession. Perhaps I frequent too many optimistic, sustainable-building websites and conferences, but for a while I was seeing the new American home through rose-colored glasses (or perhaps, green-colored glasses). I assumed they’d be smaller, resource- and energy-efficient, low-maintenance, and healthy to live in, because we are wise and would learn from the catastrophic events that cut annual new-housing starts by more than half and drove many of our colleagues, partners, and friends out of business. Unfortunately, it doesn’t appear so.

According to the latest U.S. Census data, the average new home is still a McMansion. At least, that’s what it looks like through these glasses that I just don’t want to take off. The Census Bureau reports that the average single-family house in 2013 was 2,598 sq. ft., an all-time high. The vast majority had more than two bedrooms, and 251,000 new homes had four or more. Most had at least a bath and a powder room, and 188,000 homes had three or more baths. Most had two stories.

Because we publish so many small homes and give out an annual Best Small Home award, we’ve had many discussions about where to cap the square footage of a home in order for it to qualify. If we simply work with the average, anything under about 2600 sq. ft. will work. But we’ve typically looked for projects about 600 sq. ft. smaller than that to publish as “small.” That was also the number we first chose as the limit for our award. It was Sarah Susanka who talked us up to 2400 sq. ft. I think she would have changed the award altogether, from “Best Small Home” to “Best Right-Sized Home” if we had let her.

I’m not sure “right-sized” is sexy enough to sell magazines. Sarah’s point is well taken, though; small is relative. For my family, 800 sq. ft. works. But add any of the following, and our house would be too small: another child, the desire to entertain inside, a medium-size or larger dog or other pet, or a new collection of anything that people commonly collect. Of course, I have family and friends who live in somewhat larger and much larger houses than mine, but because they also have bigger families, bigger gatherings, bigger pets, and bigger collections of all the weird things that people collect, their homes are still small.

Just like the census data, which could add up to a really big house (2598 sq. ft. with 1 bedroom and 1½ baths for a bachelor) or a pretty small house (2598 sq. ft. with 4 bedrooms and 2 baths for a family of 6), my house is sometimes small and other times more than big enough. This leads me to tiny houses, because they are always small.

Tiny is a movement

As an editor at Fine Homebuilding, I have an unscientific theory of why small houses and tiny houses are so popular in the media. The theory goes like this: Most people think that their house and the individual spaces within it are small, regardless of its actual size. When they can’t find a place to store the Christmas decorations, their house becomes small. When their kids want to make a snack while they’re cooking dinner, their kitchen becomes small. When they’re shopping for a couch, their family room becomes small (and the windows are in the wrong places). And because everyone thinks of their house as small, they want to know how to make the most of the space they have. Here, we can help.

Think my theory is bunk? You’re probably right. But for all of the people “liking” and “loving” tiny houses on their favorite social-media sites, I wonder how many would every actually live in such a dwelling.

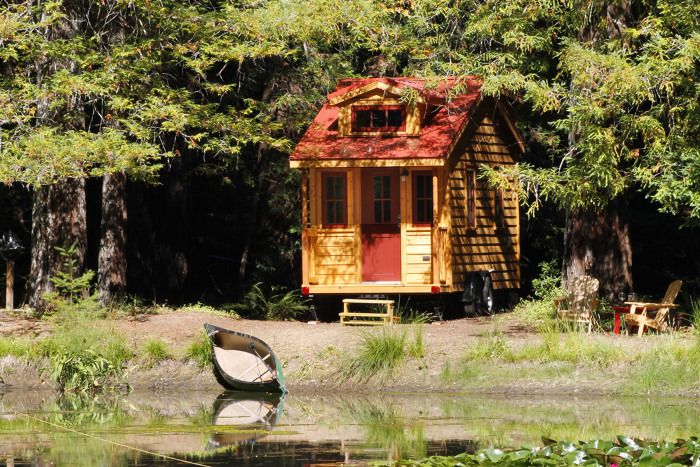

The poster children of tiny houses, designed and sold by the Tumbleweed Company, are miniscule. Tumbleweed offers four models with variations of each that range from 117 sq. ft. to 172 sq. ft. The floor plans typically include a kitchen, bathroom (not for those who like to take baths), bedroom, sleeping loft, and sometimes a small storage space. While I haven’t found a definitive size range that qualifies a home as “tiny,” in a conversation with Aaron Fagan, the author of our forthcoming feature, I remember him saying something about “not exceeding 250 sq. ft., depending on whom you talk to,” which makes the Tumbleweed models small tiny houses.

Tumbleweed’s simple designs include just what’s needed to live in a small, neat package. But design is not really what tiny houses are about, or at least it doesn’t seem so. Tiny houses seem to be about lifestyle, specifically, the idea of saving money on the initial investment in a home, on energy, and on taxes, among other things. It’s about saving time on cleaning, maintenance, repair, and the like. This is money and time that you can use instead to pursue your passions. And of course, many advocates of tiny houses promote the environmental benefits of using fewer resources and disturbing less land.

Though Tumbleweedhouses.com is the first listing in a Google search for “tiny houses,” you won’t have to look far to find a lot of other really neat completed projects, plans for sale, online information, and instructional DVDS. While you can buy a tiny house, part of the appeal is that it is an approachable do-it-yourself project that jibes with another value of tiny living: self-sufficiency.

You may not need a permit to build a tiny house in your area, but you could still run into zoning issues, as many municipalities have minimum-size requirements for legal dwellings that tiny houses don’t meet. Thus, the popularity of tiny houses as trailers: Besides the advantage of owning a traveling dwelling, this can be a way to skirt zoning woes.

It’s personal

While I am all for smart, small houses as described here as a trend in home building and design, my experience living in a small house makes me wonder how viable a solution tiny houses are for more than a few outliers. In the end, that’s a personal decision. But even with my reticence about tiny houses as a practical solution to our nation’s greatest housing issues, I do believe that the movement has a lot to offer those who value lifestyle more than things, and I look forward to learning more about that in Aaron’s article. I also think tiny houses are a lot of fun and have potential beyond primary residences: as in-law and guest apartments, attainable vacation homes and retreats, and emergency shelters–all niches that small homes have been fulfilling for some time now.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Code Check 10th Edition: An Illustrated Guide to Building a Safe House

Not So Big House

Graphic Guide to Frame Construction

View Comments

Where is the fine line we cross, when we part from meaningful description to buzz-work marketing pap?

"Spacious" 3-bedroom tract homes of the 50's - the vary homes most of us were raised in- usually came in at just about 1000 sq. ft. Get the 'big' split-level at the end of the block, and maybe you had 1200 sq. ft.

These are now to be called "small?" Huh?

Knock that same home down to only one bedroom, and you're well on your way to a 700 sq. ft. home. How many bedrooms does a retiree want, anyway?

"Square footage" is misleading in any even. Not counted are the garages, storage areas, porches, decks, patios, sun rooms, and outbuildings that are featured in so many of the 'award-winning' designs.

Also overlooked in the calculation are the massive space costs of stairways and halls - items prominent in many of the 'winners' as well. That 2000 sq. ft. multi-level might be more cramped in real terms than a 700 sq. ft. ranch.

So, what's the point to all this hype about the virtues of being 'small?' Is it nothing more than an attempt by 'reformers' to put everyone on the defensive, to appeal to our cultivated sense of guilt?

Build for the purposes of the occupant - and a pox on any artificial feel-good agenda.

Renosteinke,

Your point about the average size of midcentury tract housing is well-taken. Many of those homes had much more sensible designs than today's McMansions. It seems that in today's homes bigger is better, at the expense of good design.

We talk about square footage of conditioned living space because that's the most expensive space to build. Garages, basements, decks and other outdoor spaces cost money too, but less, and are often what makes a smaller home more livable for our modern lifestyle.

What's the virtue of a smaller house? To my mind, it's putting the cost savings of the extra sq. ft. into more important things like better air sealing, insulation, windows and doors; efficient and healthy mechanicals; durable materials where they matter most, etc. That does not describe the average home because those things come with a cost, and aren't easy to show off to your friends. But it can be attainable if we get over our hang up, or perhaps the real estate industry's hang up, with size.

Thank you for your thoughtful response.

BP

Thanks for the article Brian. I am a big advocate of going smaller for both social and environmental sustainability. Less people can afford houses today, and typical American houses are less sustainable than ever. I would differentiate small from tiny by whether or not it has to be built on a trailer because it is too small per zoning or IRC standards. I am currently building a "tiny" house 14'x7'8" but I have also designed a small 1000s/f house. Square footage gets tricky based on ceiling height. Ex. since I have a loft that brings the ceiling below 7' the area below is not habitable space, so what do I really count?

In the 1950s the average new house was 950s/f, in 1970s it was 1500 s/f and as you point out we are now over 2500 s/f. All of this while according to the last US census 1 and 2 person households are the new normal, leaving a lot of climate controlled storage for stuff.

With all respect for Susanka, she still uses Big as an adjective to describe her houses, as in "Not so Big." Jason Mclennan has said that large houses are just not environmentally sound and 450s/f per person is the biggest we should go.

I agree with both Brian's comment about the importance of shifting cost savings to better quality building and the resulting energy efficiency and Renosteinke's concern about Tiny Houses becoming just another marketing buzz word. One other consideration is the importance of location and how close community resources like shopping, workplace, and schools are to where you put the tiny house. I actually just wrote about this in my own newsletter. Here's the link if you'd like to read more on my take:

http://www.icontact-archive.com/kx-OcOhTHqIzQscHSrrh4Jk8eyJSa3BF?w=3

Alright, where to start.... First of all, taking an average of all kinds of houses' square footage, coming up with just north of 2500 square, then using that to declare McMansions are back is simply either ludicrous, or seriously disingenuous. I don't know about the rest of the country, but here in the Washington D.C. Metro area, houses in the category of "McMansion" (every single family community built in the last 15 years) has well past 2500 square feet. "Smaller" McMansions average 5,000 square feet between three finished levels. The larger ones that came later with Master Bathrooms way bigger than their living rooms managed to see 6,000 - even 7,000 square feet of finished space!

How in the hell do you even get 2,5XX square feet even being a "McMansion" at all? 3 Bedrooms now qualifies as "McMansion" now? More than one full bath? Am I dreaming this article? By those definitions, the starter home I spent my teen years in would be a "McMansion".... a duplex brick house built in 1959, with a non- eat in kitchen, three bedrooms (two of which combined had less than 200 square feet of space), and one small full bath that was tinier than a McMansion's walk in closets in their bedrooms!.

Even now, we have an updated modern built "Split Level" house, with 2,200 square feet of finished living space, and a 1,100 square foot unfinished basement. It has 4 bedrooms, 2 1/2 baths, and a decent kitchen with an eat-in area. Unlike the average McMansion though, it has a REAL Living Room suitable for entertaining guests and family nights watching t.v. (just as in the days when Split Levels were still being built), not simply to showcase to visitors.

With the basement finished, the house can grow to 6 bedrooms, 3 1/2 baths, and gain a modest sized Family Room (as compared to the ginormous basement mancaves McMansions often support). All in a space of 3,300 square feet. Hardly McMansion territory... but large enough for a family of 6 to live comfortably in. (2 Parents, 4 kids, one spare bedroom as a guest room).

It is clear to me America has some issues which probably are well past working out, as this article is showing. No sense of balance, we just have to go redefining everything to push people to extremes via guilt. There is room to improve on the houses of the 1980's and earlier, to grow them up to better suit the needs of the modern family in ways older, smaller homes would struggle to do. Our home is an example of this, and is far cheaper even in the inflated bubble prices of today than any McMansion is by at least $200K. And this is with almost 1/2 acre of land for a yard!