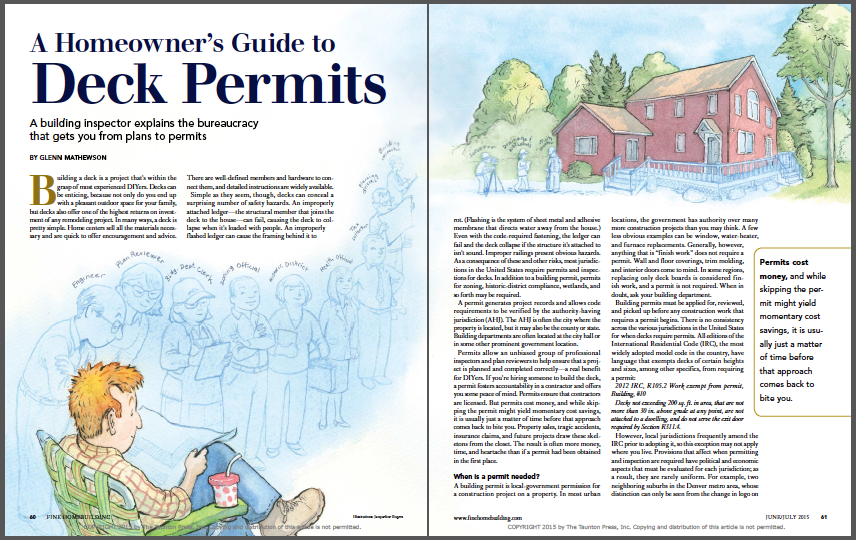

A Homeowner’s Guide to Deck Permits

A building inspector explains the bureaucracy that gets you from plans to permits.

Building a deck is a project that’s within the grasp of most experienced DIYers. Decks can be enticing, because not only do you end up with a pleasant outdoor space for your family, but decks also offer one of the highest returns on investment of any remodeling project. In many ways, a deck is pretty simple. Home centers sell all the materials necessary and are quick to offer encouragement and advice. There are well-defined members and hardware to connect them, and detailed instructions are widely available.

Simple as they seem, though, decks can conceal a surprising number of safety hazards. An improperly attached ledger — the structural member that joins the deck to the house — can fail, causing the deck to collapse when it’s loaded with people. An improperly flashed ledger can cause the framing behind it to rot. (Flashing is the system of sheet metal and adhesive membrane that directs water away from the house.) Even with the code-required fastening, the ledger can fail and the deck collapse if the structure it’s attached to isn’t sound. Improper railings present obvious hazards. As a consequence of these and other risks, most jurisdictions in the United States require permits and inspections for decks. In addition to a building permit, permits for zoning, historic-district compliance, wetlands, and so forth may be required.

A permit generates project records and allows code requirements to be verified by the authority-having jurisdiction (AHJ). The AHJ is often the city where the property is located, but it may also be the county or state. Building departments are often located at the city hall or in some other prominent government location.

Permits allow an unbiased group of professional inspectors and plan reviewers to help ensure that a project is planned and completed correctly — a real benefit for DIYers. If you’re hiring someone to build the deck, a permit fosters accountability in a contractor and offers you some peace of mind. Permits ensure that contractors are licensed. But permits cost money, and while skipping the permit might yield momentary cost savings, it is usually just a matter of time before that approach comes back to bite you. Property sales, tragic accidents, insurance claims, and future projects draw these skeletons from the closet. The result is often more money, time, and heartache than if a permit had been obtained in the first place.

What you’ll need on your deck permit application

Here are some of the details that may be required on the plans that you submit for your building permit.

- Overall size of deck and its relationship to property lines, setbacks, and easements.

- Type of foundation including depth, size of footings, and soil type expected.

- Height of deck above ground.

- Size, lumber species, location, spacing, and spans of all joists, beams, and posts.

- Railing design including material, fastener size and frequency, railing height, and baluster spacing.

- Bracing detail on elevated decks.

- Stairway location, railing location, and rise and run expected.

- All structural metal connectors and hardware to be used between framing members.

(By: Scott Schuttner)

When is a permit needed?

A building permit is local-government permission for a construction project on a property. In most urban locations, the government has authority over many more construction projects than you may think. A few less obvious examples can be window, water-heater, and furnace replacements. Generally, however, anything that is “finish work” does not require a permit. Wall and floor coverings, trim molding, and interior doors come to mind. In some regions, replacing only deck boards is considered finish work, and a permit is not required. When in doubt, ask your building department.

Building permits must be applied for, reviewed, and picked up before any construction work that requires a permit begins. There is no consistency across the various jurisdictions in the United States for when decks require permits. All editions of the International Residential Code (IRC), the most widely adopted model code in the country, have language that exempts decks of certain heights and sizes, among other specifics, from requiring a permit:

2012 IRC, R105.2 Work exempt from permit, Building, #10

Decks not exceeding 200 sq. ft. in area, that are not more than 30 in. above grade at any point, are not attached to a dwelling, and do not serve the exit door required by Section R311.4.

However, local jurisdictions frequently amend the IRC prior to adopting it, so this exception may not apply where you live. Provisions that affect when permitting and inspection are required have political and economic aspects that must be evaluated for each jurisdiction; as a result, they are rarely uniform. For example, two neighboring suburbs in the Denver metro area, whose distinction can only be seen from the change in logo on the street signs, are on opposite extremes. One doesn’t require permits for any deck less than 30 in. above the ground, while the other requires permits for all decks. This is nothing unusual. When planning a deck, always find out for certain if a permit is required.

Which code?

Which code?

That may seem like an odd question. The International Residential Code (IRC) applies almost everywhere, so there’s no choice, right? Well, there may be. The American Wood Council, which produces the document that the IRC is largely based upon—the National Design Specification (NDS) for Wood Construction—also produces an alternative building code for decks called the Prescriptive Residential Wood Deck Construction Guide and referred to commonly as the DCA 6. It’s updated periodically, and the most recent version is the DCA 6-12. It can be downloaded for free at awc.org, and many jurisdictions accept it as an alternative to the IRC.

Why bother? The IRC is a performance-based code, that is, it specifies the minimum standards a structure must adhere to. It doesn’t tell you how you must achieve those standards, though, leaving design professionals a lot of leeway but also leaving DIYers with the task of figuring out how to transform code requirements into construction plans.

The DCA 6, on the other hand, is a prescriptive code. It tells you how to build the deck and provides lots of construction details. Design professionals may find that restrictive, but those details can be very useful to a builder or DIYer.

It’s understandable to want to get started building a deck right away, and waiting for a permit can seem like a unnecessary delay. However, when a permit is required, even demolishing an existing deck or digging holes for footings can be considered “work without a permit,” something that often comes with a fine. Quite often, curious neighbors seeing or hearing any such work call the AHJ, prompting an inspector’s uninvited visit. That said, some jurisdictions allow demolition to proceed and footing holes to be dug once the permit application is in. Ask your inspector; the worst answer you’ll get is no.

Even purchasing construction materials before obtaining a permit is a bad idea. If the plan reviewer calls for changes in your construction plans, then having purchased the wrong material may cost you a restocking fee and second delivery charge. Decks are regulated with unbelievable variety across the country, so what was right on target at your last house may be prohibited at your new one. In the worst examples, you may even find the project you planned and purchased materials for is not allowed at all, or it must be built in a manner that costs more than you budgeted. The permit process can take anywhere from a few minutes until you know exactly what will be required and have clear permission to move forward.

Who is responsible for getting the permit?

The expectation of nearly all building authorities is that the person acting as the contractor is responsible for obtaining the permit. If you’re the homeowner and are doing all the work, you’re the contractor. If you do no physical work but design, organize, and contract all the various pieces of the job yourself, you are still acting as the contractor, even if you are not a tradesperson.

Some homeowners have no involvement other than cutting the check. In most cases such as this, the person hired to build the deck should be responsible for permitting. If a contractor asks that the homeowner get the permit, it’s often because the contractor isn’t licensed. While some jurisdictions don’t require contractor licensing, in others the licensing system can be a political mess. If it’s regulated at the state level, then a contractor’s license should be valid anywhere within that state. But licensing is often done at the municipal level, and a contractor may build a deck perfectly legally on one side of a street but not on the other, because that’s a different municipality and requires a separate application and fee for yet another license.

If you as the homeowner obtain the permit on behalf of a contractor, beware of a few potential problems. Primarily, you might become responsible for any failure of the contractor’s work to meet code.

If the contractor isn’t willing to pull a permit, it should raise questions about that person’s professional standing. Does he or she have liability and workers’ comp insurance, for example? Also, in many jurisdictions, unlicensed contractors cannot file liens or sue for nonpayment.

There is little consistency in this process other than the fact that, in most places, homeowners who occupy their residential property may obtain permits without being licensed contractors. The necessity of occupancy is to avoid having professional property flippers sidestep licensing requirements. Often the term homeowner permit is used, but that’s a bit misleading. Generally, it is simply the qualifications necessary to pull a permit that are softened for homeowners. Once the permit is issued, the expectations regarding code compliance, inspections, and procedures are the same.

Land-use permits make sure your project plays nice with the neighbors

Land-use permits make sure your project plays nice with the neighbors

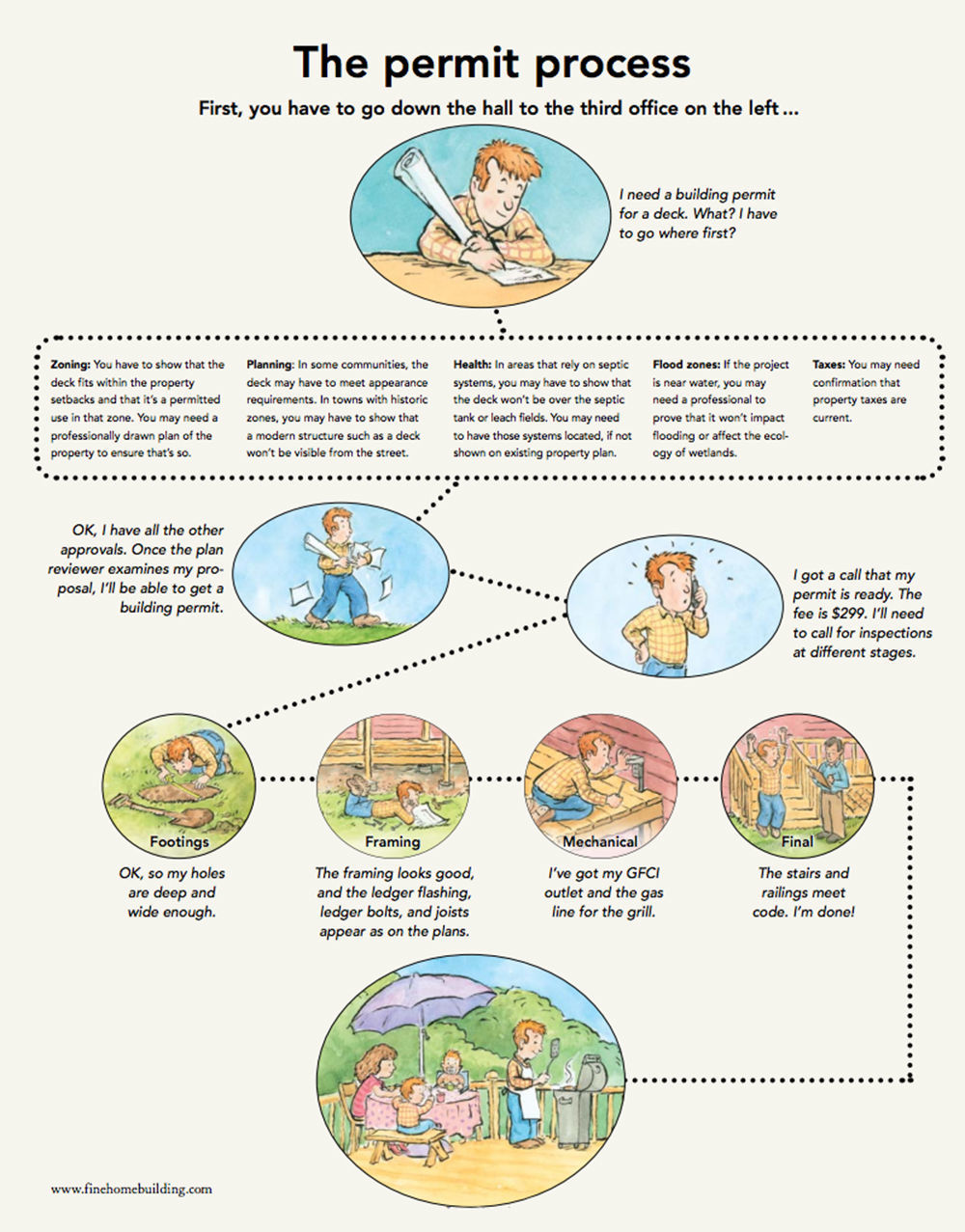

Even for a deck, the building permit is often the last in a string of permits for which you need to apply and pay. In fact, getting the building permit can be the easiest and fastest step in the process. Here’s a list of common prerequisites.

Zoning: An area’s zoning laws determine whether the proposed construction is a permitted use in that area and if the planned project is within the property’s building envelope. Most jurisdictions have setbacks, that is, areas within a specific distance from the property lines where building is not allowed. Setbacks vary between jurisdictions; even within the same jurisdiction, front, side, and rear setbacks usually differ. They may also depend on the neighborhood or whether a street or public property is adjacent.

You’ll need to show that what you propose to build does not intrude on the setback limits, which may require a plot plan of the property that shows the relationship of the new deck to the property lines. Plot plans are usually created by surveyors, and you may have a copy in the title work for your mortgage on which you can draw the proposed deck. There may also be such a plan filed with your property records at the town hall that you can copy. When a deck is proposed well away from the setback limit, a hand-drawn plot plan may be acceptable. On the other hand, construction near the setback line may require a new survey and a professional rendering.

Planning: Housing in planned urban areas and historic districts is often regulated strictly for a consistent community appearance. Homeowners associations may have similar requirements. Style, colors, and materials may be regulated; for example, a new deck may require brick columns or a specific type of guardrail. In historic districts, you may not even be allowed to build something as modern looking as a deck if it will be visible from a public way.

Flood zones and wetlands: If your proposed deck is near water, in a flood zone, or over specific drainage channels within your property, you may have to show that it won’t affect drainage. In dense housing developments, regulations require each property to work with the overall storm-drainage plan of the entire community. Any construction that could potentially disrupt this may require a review by municipal civil-engineering professionals. Also, some jurisdictions regulate any construction near wetlands to preserve the ecological and hydrological benefits they offer. These circumstances may require you to hire an engineer to provide a plan that meets regulations. This can add months to the permit process.

Taxes: Many jurisdictions will not issue a permit for new construction if property taxes are in arrears.

Health department: In areas where septic systems are used, you may have to show that your new deck isn’t going to be built above the tank or in the reserve area, a spot kept open for a new leach field should the existing one fail. This usually requires a survey of your property, but that information also may be on an existing plot plan.

How do you get a permit?

The permit process always begins with an application, and in some locales this may be the full extent of it. However, it will probably take a bit more effort. The application is likely generic for many types of work, and it’s intended to convey the details about the property, owner, and contractor. A “work description” or “project scope” field is likely but is nothing more than a written description: “Construction of a 250-sq.-ft. composite deck with stairs” would be an example of a basic project description. The information on this application allows the person who accepts the application to enter it into the plan-review process. In some areas, the plan review is conducted by the same person who accepts the application; in others, it is passed to a plan reviewer or is placed in a queue for a later plan review.

Depending on the project, supporting “construction documents” must also be submitted. For a deck, that often includes a plot plan of the site as well as plan and section views of the deck that show the structural elements such as the footings, beam, joists, railing design, and ledger-attachment details. In many cases, the plans for a deck can be simple, hand-drawn renderings.

Additionally, if any electrical work or gas lines are planned, separate permits are required. Some jurisdictions that allow homeowners to obtain building permits may require licensed contractors to perform electrical or gas work. Usually, when a licensed contractor is required, that person is responsible for obtaining the permit. In that instance, the homeowner can usually drop off the permit application that the contractor has filled out and signed.

There is almost always a fee associated with any permit, and it is based on a percentage of the construction cost. However, for small jobs, a minimum fee may apply. That’s why permit applications ask for the cost of the job. These fees help to offset the cost of inspectors and the supporting bureaucracy.

Call before you dig

Call before you dig

It’s the law: Before you begin digging holes, you have to call to have any underground utilities located. The nationwide number is 811. Call it, and you’ll be put in touch with your locating service. Someone will show up within two to three days to mark the approximate location of gas, power, and communication lines so that you can avoid them. There’s no charge, unless you hit an electric line with a shovel. Then there’s a really big charge.

Getting inspections

After a permit is obtained and the work begins, the next step is inspection. Inspections are intended to verify that the work is being done in the location, at the size, and with the materials that were approved. Inspections also visually verify that work is being performed in general accordance with the building code. It is important to understand that inspection is not intended to guarantee code compliance. Compliance is always the responsibility of the person building the project. An inspector only performs periodic inspections and can only verify what is observed. Inspections are snapshots of the process. Permitting and inspection should not be construed as quality control for a contractor’s work.

For a deck, the common inspections include the footing holes before concrete is poured, a rough inspection of the framing before any portions are covered up, and a final inspection to verify such things as railing height and whether stair dimensions are within the code. In some areas and for certain designs, the framing inspection can be performed at the same time as the final. However, fixing any code-related errors to the structure is often much more costly in time and materials after the job is complete, so I encourage getting a separate framing inspection. Any electrical work, such as adding a receptacle on the deck, requires rough and final electrical inspections as well. Extending a gas pipe out to a grill or fire pit on the deck? That requires a plumbing inspection.

Although working through the bureaucracy may feel like a burden, building codes, permits, and inspections are a necessary part of urban civilization, even for work on our own homes. If you step back, history shows that construction standards are important. They have grown as a result of building failures and the injuries and lost lives resulting from those failures.

We’ve come to expect a certain level of safety from our houses and buildings, and government oversight of construction makes those societal expectations possible. Beyond the added safety they provide—admittedly, often with added expense—permits help with keeping property taxes properly apportioned and land records up to date. Ultimately, permitting is just a wise investment. A house is a major investment, and selling your home with good permit records is like selling a car with comprehensive maintenance records. It validates the value below the shiny wax, or in the case of decks, below the ipé decking.

Tips:

Work as positively with your building authority as possible. Those folks are not the enemy that they are often made out to be.

Ask questions when you do not understand, but do not expect building inspectors to be your personal code teachers or project designers. Their job is generally to review and approve. You will often get more service from them, but consider it a bonus.

Take the time to prepare good, detailed plans. Do not be afraid or upset about plan changes (redlines). They are far easier to introduce on paper than at the job site. Prefer the eraser over the sledgehammer, and treat your plan reviewer as your ally.

When potential contractors refer to code requirements that differ between bids or that drastically affect the cost or intent of the design, check with the building authority directly. Decks are often regulated inconsistently, so assumptions can be incorrect.

Illustrations: Jacqueline Rogers

For more details and illustrations, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

N95 Respirator

Jigsaw

Get Your House Right: Architectural Elements to Use & Avoid