Guardrails vs. Handrails: Where Do You Need Them?

While they're both found on typical staircases, porches, and decks, guards and handrails have different purposes and code requirements.

Synopsis: While they are often part of the same assembly, guards and handrails serve different jobs and must follow different code requirements. Code expert Glenn Mathewson defines the two terms according to the IRC, explaining that guards are required to prevent falls whereas handrails are intended for guidance or support. He points out the location and height requirements of guards and handrails at both exterior and interior locations, along with specific code provisions for openings in the infill of guards and for handrail diameter.

Guards and handrails are like peanut butter and jelly: They can be in the same sandwich, but they’re distinct ingredients. While guards and handrails often coexist in the same assembly, they serve different jobs. But due to the casual use of the terms “handrail” and “guardrail,” the distinction can get blurred in code applications.

At least some of that confusion can be attributed to phrasing in older versions of the code. For example, up through the 2012 IRC, the code used the term “guardrail” without defining it, and referred to the use of a “guardrail or handrail” on the side of a stairway, as if the two served the same purpose and were interchangeable (even then, they were not). The 2015 IRC purged all use of the term “guardrail” and replaced it with “guard”—a term that was already in use and defined—to allay confusion.

There’s nothing in the definition of “guard” that says it has to be the typical railing that comes to the minds of many. Though we’re not talking about decks specifically here, the reason for the change in terminology was so that features on decks such as benches, planters, and built-in kitchens were not precluded from serving as guards. “Handrail” is also defined in the IRC, but it, on the other hand, does require a rail. Here are the definitions in the building code:

Guard: A building component or a system of building components located near the open sides of elevated walking surfaces that minimizes the possibility of a fall from the walking surface to the lower level.

Handrail: A horizontal or sloping rail intended for grasping by the hand for guidance or support.

As the definition implies, guards have only one purpose: They stand as a barrier at the edge of raised walking surfaces to reduce the possibility of an accidental fall. While serving in this protective role, they also invite users to purposefully lean against them or on them. Because of this, features that fit the definition of a guard must be designed to resist minimum required live loads, whether the guard is required or not. However, the architectural limitations of guards, such as minimum height and the size of openings between guard components, only apply to required guards.

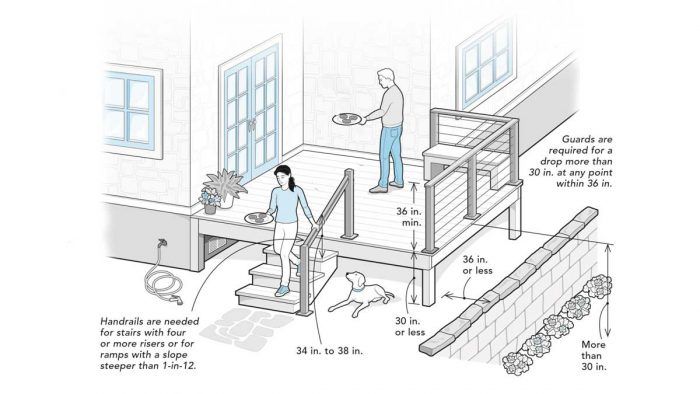

A guard is required at any portion of an open-sided walking surface, including stairs, ramps, landings, and decks, that are more than 30 in. above the surface below. And not just immediately below—if the floor or grade below drops more than 30 in. within any point 36 in. out from the edge of the elevated surface, a guard is required. This clarification came into the code to address decks that may be less than 30 in. above grade at their edge, but are located on a downslope or near a retaining wall with a greater drop. Once a guard is required, the minimum height can be no less than 36 in. (with one caveat to come). This is a reduced height from the 42 in. required in commercial buildings, and is a safety trade-off to allow greater visibility for individuals seated on decks. Safety provisions are often reduced for private residences due to occupant familiarity and to protect design freedom in our homes. These dimensions have been unchanged in the code since the 1970s.

Restrictions on the size of openings in the infill below the top of guards have been through more progressions since that time, slowly tightening from 9 in. to 4 in. The current rule is that openings cannot allow the passage of a 4-in. sphere, which is intended to prohibit a small child from passing through the guards. (This measurement is increased to 43⁄8 in. at the sides of stairs.) The larger dimensions of the past were found to allow a child’s body to slip through, but not their larger heads, resulting in tragedy. Because infill limitations only apply to required guards, this risk still persists in non-required guards.

A handrail serves a very different role: It is meant for purposeful use by an occupant while traversing an obstacle, such as a stairway or ramp. When a flight of stairs between two landings has four or more rises and when a ramp is steeper than a 1-in-12 slope, a handrail is required on at least one side. These thresholds are not related to height or the distance of a fall; they are related to how many times one must lift their legs to ascend or descend. Four 4-in. risers would only ascend a height of 16 in. and would not require a guard, but would require a handrail to be available to assist someone’s movement. It’s worth noting here that a handrail is just a rail. Anything below or next to it—be it a guard, wall, post, or something else—is not part of the handrail. It can be attached to almost anything so long as it meets loading requirements.

Handrail height also differs from guard height. It is measured vertically from the finish surface of a ramp or the imaginary sloped line connecting tread nosings on a stairway, and can be anywhere from a minimum of 34 in. to a maximum of 38 in. in height. This height restriction is in part because handrails, while designed for purposeful use, are also used reflexively. Even when not using a handrail, an accidental slip will result in a reflex to grab it. And here’s where the caveat about guard height comes in. As previously stated, guards are required on the sides of stairs where there’s a drop of more than 30. in from the edge. But while guards must typically be at least 36 in. tall, guards on stairs can be as low as 34 in., measured from the line connecting tread nosings—the same as the minimum height for handrails. This holds true whether the guard has a handrail attached to it or not. The top of a guard can also serve as a handrail, and when that’s the case, the minimum and maximum heights for handrails— 34 in. to 38 in.—also apply to the guard. Where the top of the guard doesn’t serve as a handrail, there’s no maximum limit on its height.

Graspability is where handrails get very specific in their design. Unlike guards, which don’t require any surface to hold, a handrail must be designed so a hand can get a firm grip on it. The key here is grip, not pinch. A typical handrail must have a diameter no greater than 2 in. so that a small hand can wrap its fingers around it, not just pinch the sides. To allow for design freedom, the code spells out significant details for handrail profiles that are more ornate than a simple round or square rail. For these handrails, a “finger recess” is described for both sides of the profile in a range of allowable locations. Though the code spells out in detail these profiles as “Type I” and “Type II,” it also makes it clear that other profiles are permitted that offer “equivalent graspability.” While it’s easy to get lost in the specific dimensions elaborated in the code, the intent is simple: Users should be able to grasp the rail with fingers and thumb hooked around it.

Handrails and guards, whether required or not, cannot become booby traps. Much like the ’80s movie Field of Dreams—“If you build it, he will come”—if a guard or handrail is available, an occupant will expect it to bear their weight. With this consideration, all guards and handrails, required or not, must resist a 200-lb. concentrated load at any point along their top surface and applied in any direction. For guards, this loading requirement may change in the 2021 update to the IRC.

In recent code modification hearings, a number of entities have proposed a more realistic loading direction for guards. While appropriate for handrails, the question has arisen of whether considering loads pulling inward, upward, or inline on a guard is appropriate. Load resistance in these directions is dictated by the phrase “in all directions,” but it’s not really justified—there is no requirement for a graspable feature or any mention of protecting one from a backwards fall to the surface they are standing on (were they to yank backwards on the guard). A proposal to change guard design loads from “all directions” to “outward and downward” is likely to appear in the 2021 IRC.

Perhaps more importantly, a change to separate guards and handrails from one another in the minimum design load table has already been approved for the 2021 IRC, which will drive home the importance of evaluating these features independently of one another.

Glenn Mathewson is a consultant and educator with buildingcodecollege.com.

Drawing: Kate Francis

From Fine Homebuilding #289

More from Know the Code:

Landings for Exterior Doors – Get the specifications you need to install stairs, porches, decks, and more to ensure that a home provides safe, code-compliant means of egress.

Changes to the Building Codes – Code expert Glenn Mathewson explains how changes are made to the International Residential Code, with a chart detailing the code-development process.

Electrical Outlets by the Numbers – Building codes dictate specific height and spacing measurements for receptacles and switches. Learn what the most common dimensions are and why.