Neighborhood Net Zero

This builder-friendly spec house fills out a narrow lot in a contemporary community.

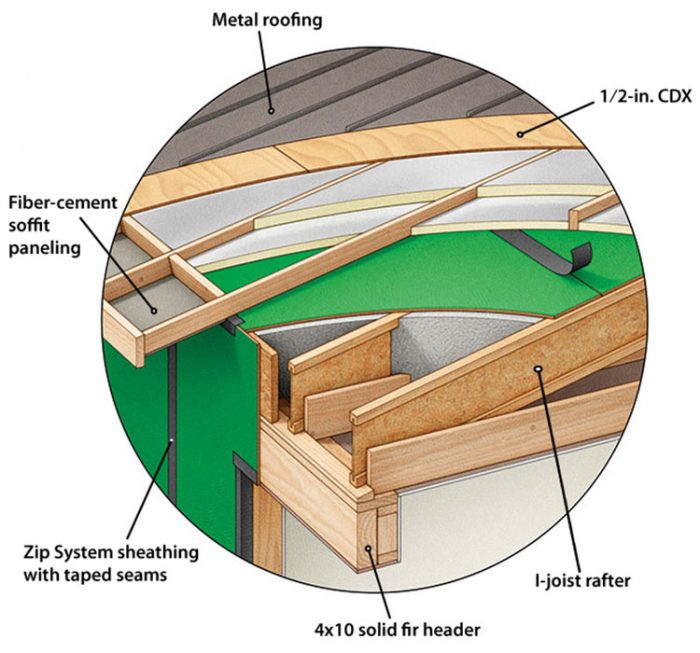

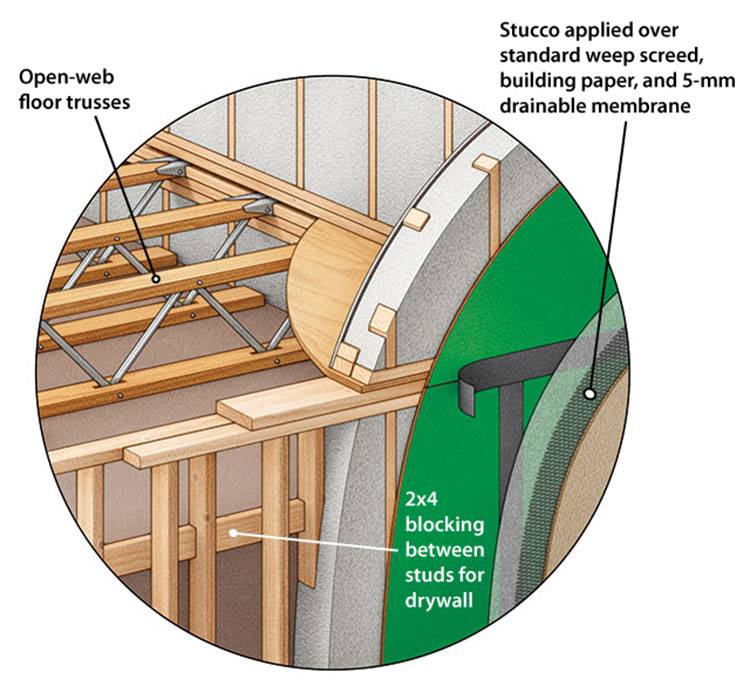

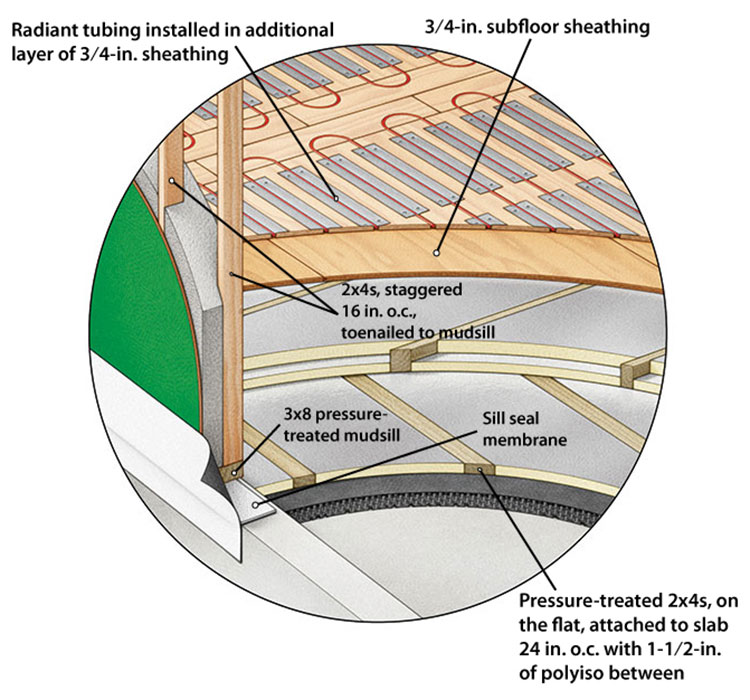

Synopsis: Fine Homebuilding’s 2018 Best Energy-Smart Home Award went to Eric Woodhouse for a contemporary split-level spec house that achieved close to Passive House levels of airtightness. Rigid insulation was installed over the slab, and then 7-1/4-in.-deep double-stud walls were dense-packed with cellulose insulation. Open-web trusses were used for the second floor, and I-joists for the roof framing. Zip System sheathing is the primary air and water barrier on the walls and roof, and the roof system is unvented with dense-pack cellulose in the rafter cavities in addition to foam installed above the sheathing. The house is heated with a homebrew version of hydronic radiant tubing installed under the finished flooring, controlled by a Nest thermostat. The walls have conventional stucco over a ventilated rainscreen assembly, and there is a PV system on the roof sized to produce more energy than the building needs. The article includes in-depth drawings of the roof, wall, and slab details.

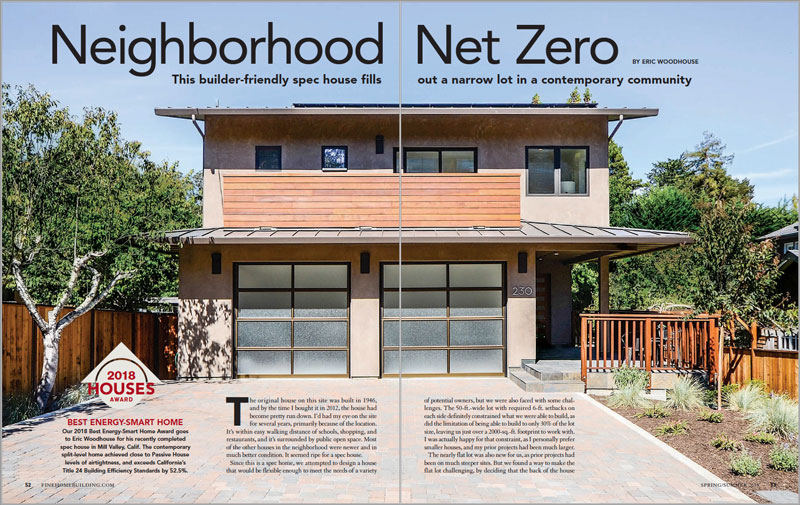

The original house on this site was built in 1946, and by the time I bought it in 2012, the house had become pretty run down. I’d had my eye on the site for several years, primarily because of the location. It’s within easy walking distance of schools, shopping, and restaurants, and it’s surrounded by public open space. Most of the other houses in the neighborhood were newer and in much better condition. It seemed ripe for a spec house.

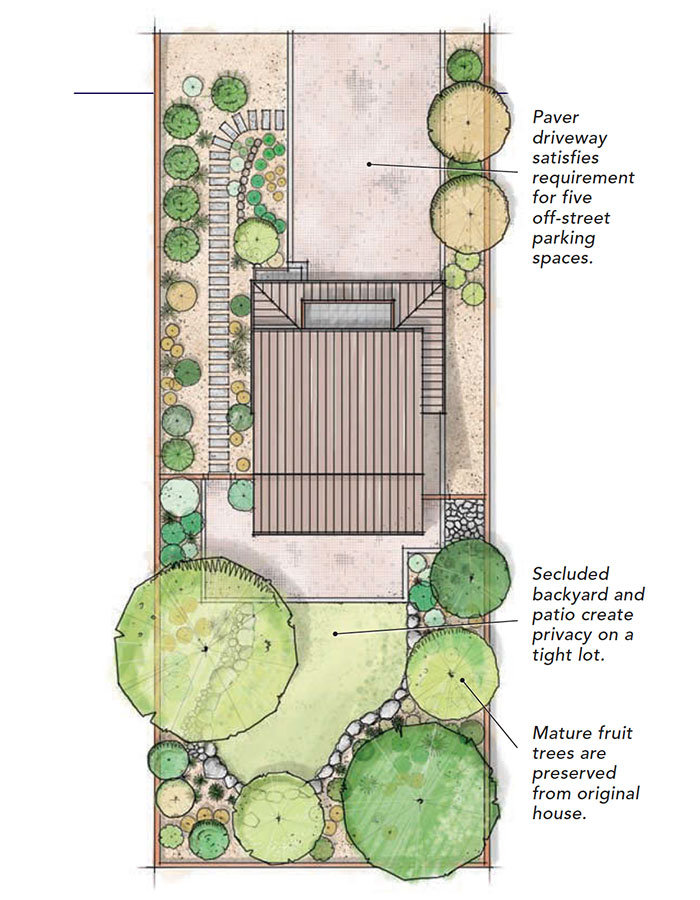

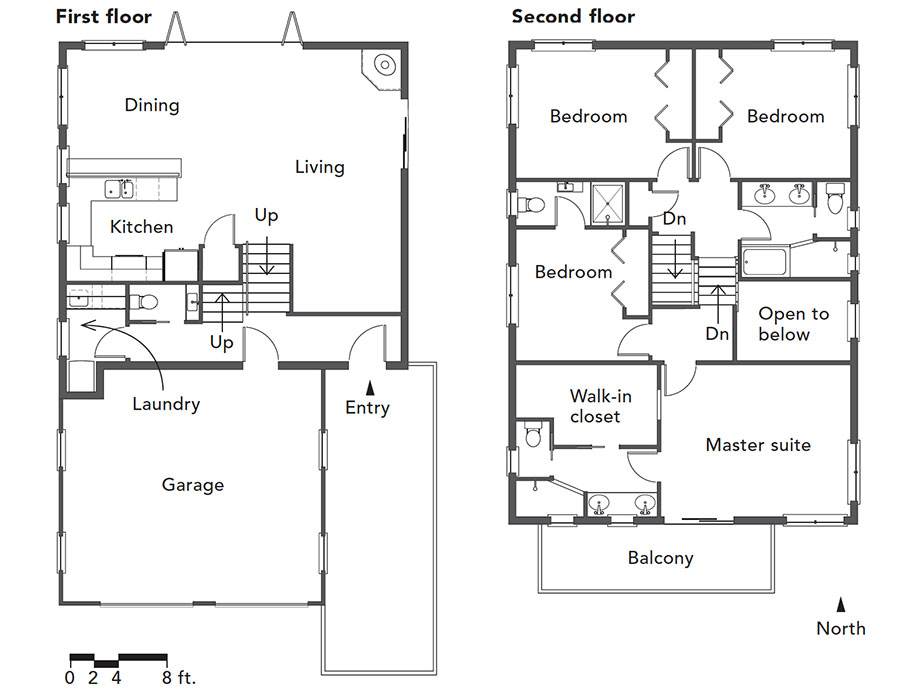

Since this is a spec home, we attempted to design a house that would be flexible enough to meet the needs of a variety of potential owners, but we were also faced with some challenges. The 50-ft.-wide lot with required 6-ft. setbacks on each side definitely constrained what we were able to build, as did the limitation of being able to build to only 30% of the lot size, leaving us just over a 2000-sq.-ft. footprint to work with. I was actually happy for that constraint, as I personally prefer smaller houses, and my prior projects had been much larger.

The nearly flat lot was also new for us, as prior projects had been on much steeper sites. But we found a way to make the flat lot challenging, by deciding that the back of the house should open to the backyard at grade, with no steps. This led to the split-level design.

Backyard Retreat

A mixed bag of materials

When building for energy efficiency, decisions about framing and insulation go hand in hand. And when building a spec home, size matters. It seems that most energy-efficient homes are wrapped in rigid foam these days, but we had a different approach.

We did install rigid insulation over the slab, over which we installed subfloor sheathing. We didn’t carry the rigid-foam plan to the walls, though. We had done exterior foam on a previous job and decided the work was kind of a pain, so we decided to try something else for the walls on this build. We ended up going with 7-1 ⁄ 4-in.-deep double-stud walls, which we dense-packed with cellulose insulation. I would have preferred a thicker wall, but a deeper double-stud wall would have meant a further reduction in our interior square footage, so the wall design was a compromise.

We used open-web trusses for the second floor because they gave us nice, stiff floors and made it fast and easy to route the plumbing and electrical. For the roof framing we opted for I-joists, which gave us longer lengths and spans than we could get from 2x12s, and are far lighter.

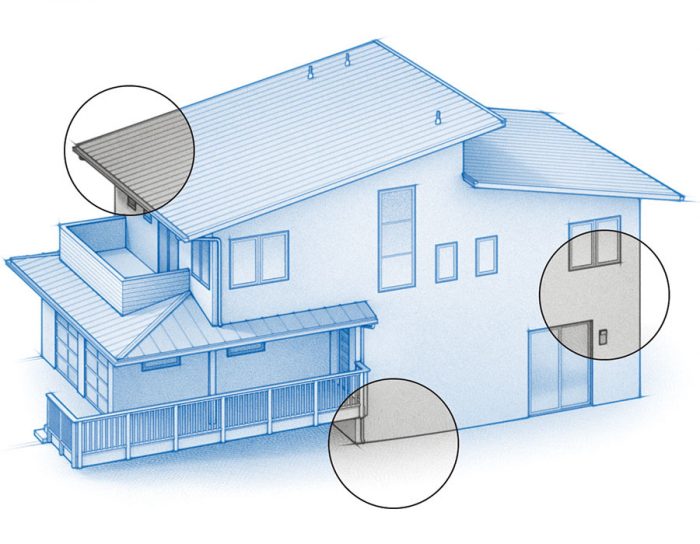

As is typical of many energy-efficient builds nowadays, we relied on Zip System sheathing with taped seams as our primary air and water barrier on the walls and roof, which we framed without overhangs to allow for faster and easier air-sealing at the wall-to-roof intersection.

The roof system is unvented, and has dense-pack cellulose in the rafter cavities, in addition to foam installed above the sheathing. In places where the roof didn’t have drywall in contact with the insulation (over bedrooms with flat ceilings, for instance), we used Intello membrane in place of the usual cellulose netting, supporting it with 1x strapping, in order to maintain our air barrier.

We buttoned up the envelope with Alpen windows and sliding doors, which have a clear film between the panes of glass for a semi-triple-pane effect. The large NanaWall door, however, is a true triple-glaze.

Making spec work

I grew up in Mill Valley in the ’60s and ’70s, bought my first house here in 1989, and have lived in town ever since. As a result, I know the various neighborhoods better than most— certainly much better than I would in any other town—which is why I’ve focused my work here. This town has a lot of older homes, many poorly built or poorly maintained. As their often-older owners move on, a few become available every year, and those are the properties I look for.

Ideally, the property has a large lot, southern exposure, views, and easy access (if it’s way up in the hills, this impacts both

ease of construction and marketability), and is walkable to at least some services. In reality, I always have to compromise on one or more of these criteria. But I’m very picky—I don’t buy a property I don’t like, and I don’t buy something unless it’s in an area that will sell for $1000 or more per sq. ft. when completed. I made that mistake early on, and learned from it.

“I consider my first spec project—a property I bought for way too much money, developed, and then sold a few years later at a considerable loss—as ‘tuition’ paid toward my education in building spec houses.”

When I decided to get into this business about 12 years ago, my interest was in sustainable construction. I wanted to build the best houses I could and still make a living. I’m really not interested if I’m just building junk to make a profit. But truthfully, I don’t think the market cares much about what I think makes a quality building: good flow, space efficiency, airtightness, insulation, high-quality windows, efficient mechanicals, healthy air quality, or even PV on the roof. Perhaps it’s different in harsher climates where utility bills are higher, but here in California my experience is that energy efficiency and sustainability make a property easier to sell, but don’t lift the price much, if at all. Buyers like low energy bills, but my guess is that they would pay the asking price regardless.

The things that sell here are square footage, bedroom and bathroom count, and “wow” features like NanaWalls and highend finishes. I don’t have much control over the square footage—the lots are small and floor area is limited to a percentage of the lot size. I try to strike a balance between all of the other things, with a lot of collaboration with my wife, my contractor and crew, friends, my realtor, vendors, and designers. It sounds like design by committee, but it seems to work. We beat every issue to death, and then ultimately I make the decision. In some cases, I choose things more for the market than for my own taste. For example, the white cabinets on this project would not have been my choice, but everyone paying attention to trends said that was the way to go, so we did.

—EW

Construction at a glance

Relying on a mixture of framing materials and types of insulation, this energy-efficient home is a prime example of highperformance-, climate-specific-building best practices.

Air leakage, by the numbers

The air barrier begins at the top of the foundation, where ProtectoWrap Triple Guard sill sealer bridges the gap between mudsill and concrete. From there, Zip System sheathing extends up the walls and onto the roof with all seams and transitions taped.

We did our first of two blowerdoor tests after the building envelope was complete, but prior to insulation. We figured at that point we’d poked all the holes in the shell there were going to be (and hopefully filled them all with foam, caulk, or tape), but the shell was still accessible, so if we found leaks we could likely still fix them.

In this case, the airtightness number was 0.86 ACH50—good enough that we only spent about 10 minutes walking around feeling for any obvious opportunities for further tightening before we got started with the wall and roof insulation. Our second blowerdoor test, at the time of final inspection, rewarded our efforts with a nice reduction in the airleakage number—dropping to 0.69 ACH50, which is just above Passive House requirements.

Homebrew radiant heat

We used Warmboard on our first project in 2010, and while I loved the speed and ease of installation, there were downsides for us as well. Not only are prefab systems relatively pricey (we paid $8 per sq. ft. for materials alone), but the need to install the tubing before framing interior walls meant we needed to cover the radiant tubing after installation and pray nobody dropped something sharp or heavy in the wrong place and left us with a smashed or punctured tube. By installing the radiant after the framing, insulation, mechanicals, and drywall were all complete, we are able to minimize exposure.

The system we use relies on heat-transfer plates we buy from BlueRidge Company (blueridgecompany.com). We use heat-transfer plates under wood floors, but under tile we figure the thinset is a good enough conductor that plates aren’t needed. You can buy narrow plywood panels with curves routed into them, allowing you to define a pathway for the tubing. We opted to cut and mill separate pieces of plywood for each loop. This method is far more labor intensive, but also increases flexibility of design. The heat-transfer plates themselves are about $0.50 per sq. ft.; cost beyond that includes only plywood, and obviously a fair bit more labor (my rough calculation on the labor is about $3 per sq. ft.). But the payback is that you can put heat exactly where you want it, and not where you don’t (e.g., under cabinets, in some closets, etc.).

My guess is that our system is somewhat less efficient than Warmboard or other prefab options, since the aluminum is only covering maybe one-third to one-half of the total floor area, but I’ve been living in the house where we first installed a system using this technique for the last three years and I haven’t noticed any issues of warm or cold areas of flooring.

—EW

Modest mechanicals and durable finishes

For heating, we’ve had excellent results with our homebrew-version hydronic radiant tubing installed under the finished flooring. There are seven zones, each controlled by a Nest thermostat, and hot water comes from the same Sanden SANCO2 heat pump that provides domestic hot water, which is located in a mechanical room.

Bedrooms: 4

Bathrooms: 3-1 ⁄ 2

Size: 2049 sq. ft.

Cost: $525 per sq. ft.

Completed: 2016

Location: Mill Valley, Calif.

Designers: Eric Woodhouse; Greg Shaw

Builder: Greg Shaw Construction

There is no cooling system in the house. Instead, we have clerestory windows on the wall above the stairway and in one of the bedrooms, each electrically operable so that they can be opened for stack-effect ventilation and night flushing.

Mechanical ventilation is provided by a Zehnder ComfoAir 350 HRV. We originally planned to put the HRV in the crawlspace/mechanical room, but during construction we realized that there was room for it in the ceiling above the kitchen, which kept it inside the conditioned envelope and placed it centrally in the building, reducing the length of the duct runs.

The roof-mounted photovoltaic system consists of 27 SolarWorld 285w modules for a total of 7.7kw. It was sized to produce more energy than the building needs, in the event future owners want to charge an electric vehicle. For the exterior, we chose conventional stucco over a Stuc-O-Flex WaterWay 3-mm ventilated rainscreen assembly. Our local inspectors like stucco because it’s fire resistant, and I like it because the color is integrated into the top coat, so the building should never require paint. I expect the same longevity in the metal roofing, which essentially lasts forever. The standing seams also make solar-panel attachment fast and penetration-free.

For the interior, we chose finishes that catered to the market. Hence, there’s a lot of white. But we also opted for durable surfaces and took opportunities wherever we could to further our sustainability goals. To that end, all lighting is LED, all plumbing fixtures are WaterSense listed, and all appliances are Energy Star rated.

—Eric Woodhouse builds spec houses in Mill Valley, Calif. Photos by smsmithphotography.com.

For even more photos, floor plans, and information, please click the View PDF button below.

From Fine Homebuilding #275

Click here for a slideshow of photos of this project.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

100-ft. Tape Measure

Original Speed Square

Anchor Bolt Marker

View Comments

It’s great to see a house in California with hydronic heating.