DIY Passive House

This is the story of an energy-efficient house, a rain tank, an incredible view, and two determined homeowners who didn’t quite realize what they were getting themselves into.

The Best Energy-Smart Home: Fine Homebuilding’s Best Energy-Smart Home Award goes to a unique team of collaborators: architect George Ostrow, principal of Seattle-based VELOCIPEDE architects, and two deeply dedicated DIYers committed to building the most ecologically responsible house possible. Its simple structure belies the complexities of the build. Ten years in the making, this certified Passive House in Carnation, Wash., is a study in conservation, building science, and one couple’s unfailing grit.

I’ve been involved in eco-building for 25 years in Seattle, earning awards for LEED homes and a LEED Platinum grocery store. So when Gary and Marian Aamodt contacted me in 2009, looking to build the third-ever Passive House in Washington state—and my first—I was intrigued by the challenge. But the Passive House standard was only the beginning of what made this project so unique.

Long-time environmentalists, the Aamodts wanted their next home to be comprehensively green: low-VOC and net-positive energy, with formaldehyde-free materials, FSC-certified lumber, and solar electricity and hot water. In the end, they stayed on the grid only because digging a 1200-ft. trench was easier than dealing with batteries—and cheaper, too, factoring in future credits for excess energy production. To reach their ambitious goals on a limited budget, the Aamodts had another uncommon request. They wanted to do the construction themselves.

I first became excited about Passivhaus in 2009 when the founders of Passive House Institute U.S. (PHIUS) spoke to a packed room at my local library. I had to stand outside in the bushes for their talk, looking in through an open window. The rainbow colors of their thermal images captivated me: This was serious building science!

Facing my own first attempt, I admit to being intimidated by the Passive House Planning Package (PHPP) spreadsheets and complex energy calculations required to meet the most stringent energy standard in the world for buildings. I read and reread the Passive House manual and carefully worked my way through the software. When I hit a roadblock, I was able to get advice from colleagues who had taken PHIUS’s intensive training—such is the collegial, cooperative ethos of both the Northwest EcoBuilding Guild and Passive House Northwest.

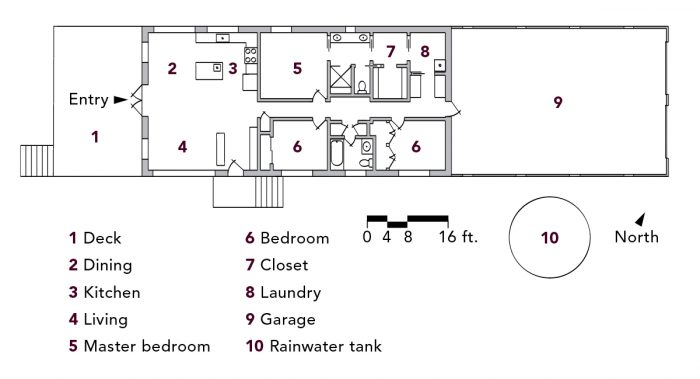

The Aamodts’ hilltop site sits 250 ft. above the town of Carnation, Wash., in the Cascade foothills about 25 miles east of Seattle. Their 270° view is spectacular, but the buildable portion of the acreage is long and narrow. Gary and Marian wanted three bedrooms and two bathrooms in 1600 sq. ft. of living space—on one level, so they could age in place. They also needed an oversize garage for a trailer, two cars, and a small workshop.

One level with a view

The driveway enters from the wooded end of the site, so the elongated floor plan transitions from garage to bedrooms to an open living and dining area and large deck with beautiful views of the Cascades. The office, bedrooms, and bathrooms come off a central hallway, which leads to the open kitchen/living area, big deck, and best views.

The Aamodts’ goals, the site, and the farm buildings in the vicinity suggested a barn form. The design emerged as an 8-in-12 gable roof extruded 98 ft. long. The access drive enters from the wooded end of the hilltop, so the layout transitions from garage to bedrooms to a great room and an outdoor deck with front-row views of Mt. Rainier.

The homeowners’ plan to DIY the construction led me to keep the design and buildability dead simple. The cross-section is the same throughout—insulated over a crawlspace in the living area, switching to exposed framing on a slab in the garage. This simplicity not only minimized thermal bridges but also helped the homeowners frame their first house with relative ease.

|

|

In the living half of the house, I used a frame-within-a-frame strategy to allow me to adjust the insulation thickness to make the Passive House calculations work. It also let the Aamodts dry in the building quickly and complete the remainder at their leisure. The double-stud walls create a cavity that requires fire blocking every 10 ft. We used plywood for that, face-nailing it to the aligned studs in the outer and inner walls, which also stiffened the walls along their considerable length.

To minimize heat loss, eliminate unnecessary lumber, and make the house easier to build, the design employs advanced framing techniques, meaning the roof trusses, ceiling joists, and wall studs are all plumb above each other, 24 in. on center, with floor joists set at 16 in. o.c. The window widths are subordinate to the stud layout, taking up one, two, or thee bays exactly. In fact, there are only six off-layout studs in the 250 linear ft. of exterior shell—caused by 3-ft.-wide entry doors.

To further assist my homeowner-builders, I went beyond the usual elevations and cross-sections to create framing drawings in AutoCAD for the exterior and shear walls, which our structural engineer, Aaron Pambianco, then reviewed and adjusted. In our pursuit of the extreme, we used a single top plate—a misstep that forced the Aamodts to raise the long walls all at once.

Water collection

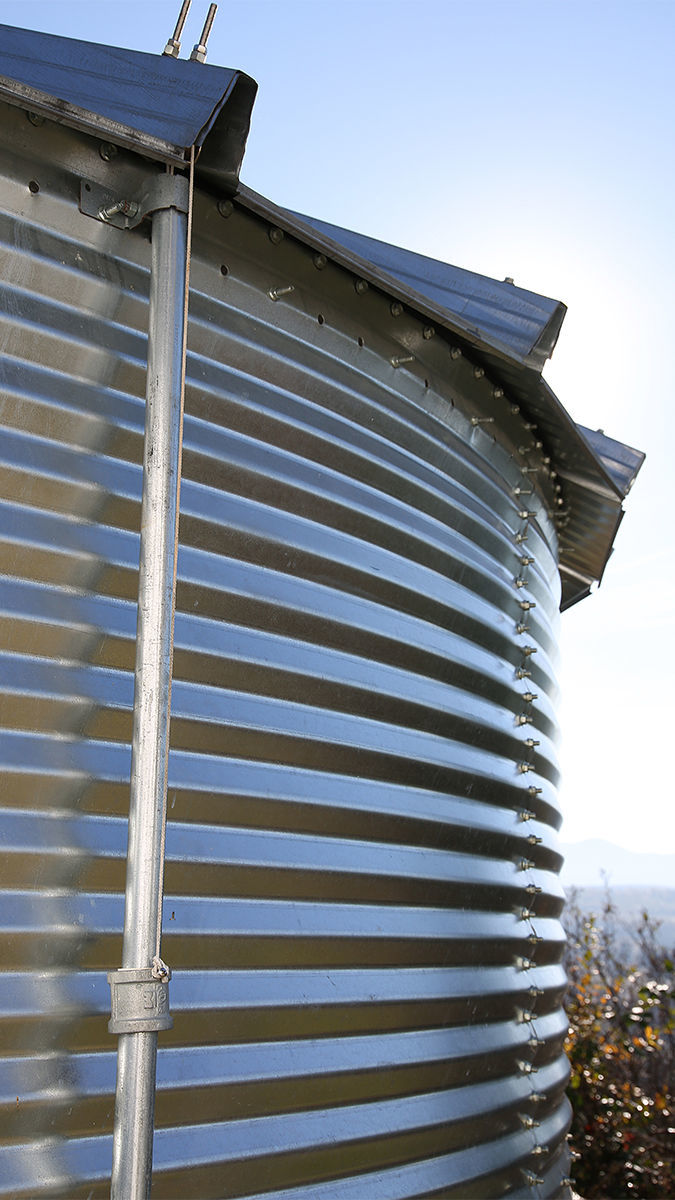

The amazing site had one substantial defect: no water. The Aamodts got a $32,000 bid for a 470-ft. well, with nearby wells experiencing weak flow and arsenic tainting. I had incorporated potable rainwater harvesting systems as backup supplies for two previous houses, so I suggested that the Aamodts use one for 100% of their water needs.

The rainwater system would be the same price as the well and it would offer certain success in the rainy Northwest. A civil engineer, Chris Webb, designed the system and wrote a detailed operation and maintenance manual.

It works like this: Carnation’s 62 in. of annual rainfall land on the house’s steel roof, which is painted with Kynar, a polymer coating. The rain flows into a stainless-steel gutter and downspouts to a pair of prefilters that siphon off debris and send it into an 8800-gal., PVC-lined storage tank that sits next to the house. The tank has to be full in May to last through our dry summers. Inside the garage a 1-1/2-hp pump pulls water from the tank through three successively finer filters to remove particulate matter and then a UV light to sterilize it and make it potable. No chlorine is involved, which makes the water delicious.

The water-supply project added a year to the construction schedule, beginning with a five-month battle with the sewer review board. The water-treatment system in the garage was so complex that Gary had to create a spreadsheet to track all the pipes, fittings, filters, valves, etc. And it came with a steep learning curve; clogged filters and a stuck water-level gauge led to a couple of emergency water deliveries early on. But he seems to have the system mastered now.

Gary created his own water-level indicator, which shows the tank is still half-full after a dry summer.

SPECS

|

|

George Ostrow founded VELOCIPEDE architects 21 years ago to focus on deep-green single-family, multifamily, and commercial projects in the Pacific Northwest.

Photos by Asa Christiana, except where noted.

Floor plan by Patrick Welsh.

From Fine Homebuilding #283

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Get Your House Right: Architectural Elements to Use & Avoid

All New Bathroom Ideas that Work

Homebody: A Guide to Creating Spaces You Never Want to Leave

View Comments

I'm envious of them being able to find designer to design a passive house and take into consideration it is being built by the owners. I've been searching for years now on how to accomplish same thing. Even spending thousands of dollars on architects who don't seem to care about energy efficiency or even read the elaborate details given for site planning and requirements. We need to make it easier for people to build passive houses by making it simpler to find out how to do it. There is so much information spread out over so many resources that makes it difficult to put it all together into "best practices".

I think I spied a big honkin' RV in the background in the first pic. A home out in the middle of nowhere so that you have to drive everywhere. Tell me again, Mr. and Mrs. Virtue Signalers, about all that green sustainability stuff.

Excellent Job