Community Solar Farms: An Alternative Path to Renewable Energy

Solar power developers appeal directly to homeowners and renters in order to expand utility operations.

In 2020, solar power development flourished in the U.S., with nearly 9.6 gigawatts (GW) of new utility-scale operations going on line–a record. By the end of the year, according to the Berkeley Lab’s year-end report, there were some 969 projects in the U.S. with capacities greater than 5 megawatts (MW), the benchmark that the lab uses to separate “utility-scale” photovoltaic arrays from everything else.

Projects can run in the hundreds of MWs, so it would be easy to dismiss something as modest as the Curravale Solar Farm in rural Knox, Maine. With a capacity of just 1.95 MW, Curravale and its 5200 solar panels would produce just enough electricity to supply 250 households as its developer, ReVision Energy, planned to flip the switch just before Thanksgiving.

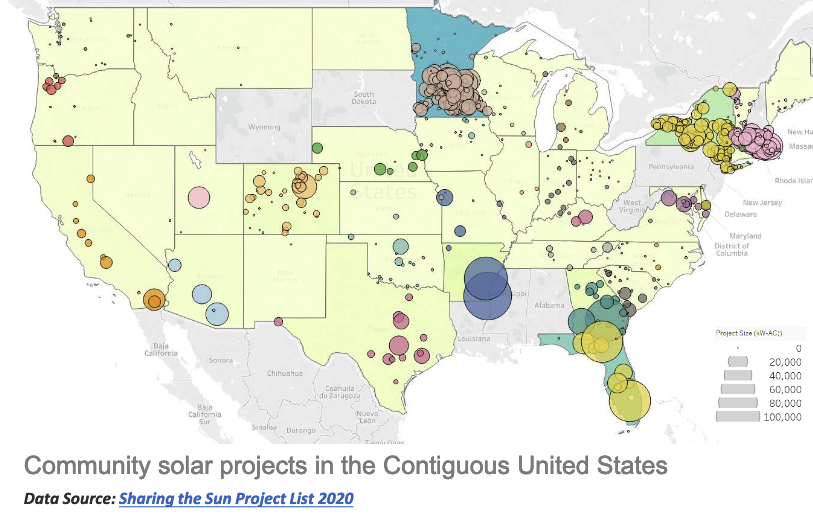

But Curravale has something that much bigger utility projects do not. As a community solar farm, it offers consumers a chance to buy into renewable energy directly when installing solar panels on the roofs their own homes is impractical, not permitted, or too expensive. The country’s rapidly expanding network of community solar farms has, on average, more than doubled its total capacity every year for the last decade, reaching a total of 3.2 MW and more than 1600 projects around the U.S. by the end of 2020.

Only about half of all buildings in the U.S. are large enough or face the right direction to make rooftop solar an option, according to an organization called Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Community solar is a way of bridging the divide between solar haves and have-nots.

Far from springing up only in places like the sunny Southwest, community solar has made some of its greatest inroads in northern states, where solar potential is lower. Minnesota, for example, is at the top of the list with 789 MW of capacity at solar farms now in operation, and another 483 MW in the pipeline, according to a “Sharing the Sun” report published earlier this year by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). Two other cold-climate states, Massachusetts and New York, are among the top five producers nationally.

“Solar growth overall has been pretty rampant,” says Jenny Heeter, a senior energy analyst at NREL and the lead author of the report. “It’s definitely a growing area that people are becoming more familiar with as they see actual projects in their states.”

More than one financial model

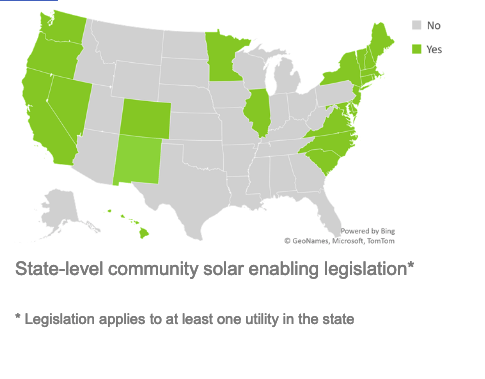

Opportunities for consumers depend on regulatory policies in the states where they live. In some states, development is brisk and projects are getting bigger. Both Florida and Arizona saw community projects of more than 50 MW last year. In active states, customers may be able to choose between more than one provider, while in other states community solar essentially does not exist. While Minnesota solar is booming, New Mexico, lists a single project in NREL’s state-by-state compilation that goes back to 2006, a 76 kW project built in 2012. Beyond that, nothing.

“Generally, states with the most community solar are not necessarily the states with the most solar energy potential,” Heeter said. “A lot of community solar is driven by state-enabling policy frameworks or utility programs. It really is those enabling programs and policies that drive it, not necessarily where there is more or less solar potential.”

Community solar projects, which average about 2 MW, can be developed and marketed in one of several ways. Although utilities can bring projects on line themselves, it’s more common for a third-party developer to finance and build a solar farm, and then sell credits for the electricity to consumers.

Customers can participate by buying panels outright or by subscribing to the farm’s power output without buying any equipment. In an ownership arrangement, the developer is offering a portion of a solar farm for sale to the consumer, just as if the solar panels went up on the customer’s roof. A share is based on how much electricity the consumer typically uses in a year. The purchase can be in cash or financed with a loan.

Nate Bowie, vice president of sales at ReVision Energy, says the process starts with an assessment of a customer’s electricity usage, so a percentage of the solar array can be matched according to demand. When the total capacity of the farm has been distributed among new customers, it’s essentially closed. On average, Bowie said, a solar farm customer needs about 9 kW of capacity and will pay roughly $24,000 for those panels, although he cautions that costs can vary due to such factors as interconnection charges with the utility, and the overall quality and location of the site.

Most customers finance their purchases, ideally trading their monthly utility bills for loan payments on the panels. These customers also get to take advantage of the federal income tax credit (ITC) on solar panel purchases, currently at 26%. (The ITC is scheduled to fall to 22% by 2023 and end entirely for residential projects after that.) Should a customer’s circumstances change, the share in the solar farm can be sold (or bequeathed).

“Now I’m getting the solar benefit—great for the earth, feels good for me, and I’m saving that much on my utility bill,” Bowie said. “I’m just swapping it. I’m swapping my utility bill for a loan payment. So, it’s really attractive, especially if you’re not a perfect solar candidate at your home.”

Billing and other details vary by state. In Maine, solar customers will still get a bill from the electric utility for a basic distribution charge. But the electricity produced by their share of the solar farm will be credited to the account at the retail rate. Customers bank kW hours of electricity in the summer, when production outstrips demand, and draw on banked credits during the winter. In addition, customers will pay an annual fee to ReVision to cover maintenance, tax filings, and other expenses. At the moment, the annual cost is $22 per kW of capacity.

Customers can be many miles from the solar array, as long as they are in the same utility service area. The developer makes money just as it would by selling solar panels for an individual rooftop installation, covering the costs of the equipment and developing the site and building in a profit margin.

The other way to participate in a community solar project is via subscription. The developer starts by allocating a portion of the solar farm to a customer based on how much electricity the customer is likely to use. The customer doesn’t own anything, but gets credit for the amount of electricity generated at the facility, explained Keith Hevenor, communications manager for Nexamp, a developer with more than 300 solar farms on line around the country.

At the end of the month, the customer gets a bill from the utility that includes a credit for power generated at the solar farm. Nexamp sends its own bill for that power, minus a discount, now set at 15% in Maine. The net effect is that the customer gets a 15% discount on what he would have paid to the utility. The customer doesn’t have to sign a contract, and has no long-term financial commitments.

“The downside of that for some people is the second bill,” Hevenor said. “Often we get the question: ‘What’s the catch? You’re telling me there’s no fee to sign up and cancel at any time. There’s nothing to install and I’ll save money. So, what’s the catch?’ Well, right now the catch is you’re going from one bill to two bills. For some people that’s a deal breaker.”

Nexamp’s profit margin comes in large part from the difference between what the utility pays the company for the electricity and how much it costs for Nexamp to produce the power. The company also gets the federal income tax credit.

“One of the most common misconceptions is the notion that if you are in community solar, you are getting clean energy to your home,” Hevenor said. “We want to be really careful not to have people misunderstand the model, and states are very particular about us not misrepresenting that as well. At any given moment, even if you’re subscribing to a community solar farm, the electricity is pouring into your house may be coal, gas, or oil-fired, even though you’re subscribing to this project. That’s where we’re always trying to be careful to explain to people that you’re not receiving clean energy directly.”

However, the more solar energy that’s supplied to the grid, the less electricity will be needed from sources that burn fossil fuels to generate it.

Hevenor said land owners who provide property to developers like Nexamp also benefit through lease payments. It typically takes between five and seven acres of land to get a MW of capacity, so leases are not insignificant for owners where large arrays are developed. Leases typically run for 25 years, with an option to renew. In the case of a farmer who wants to return the land to agricultural production, the developer simply pulls up the steel poles that support the panels, breaks up the small concrete pad for interconnection hardware, and recycles the panels. The land is essentially back to what it was.

The Maine interconnect debacle

Solar developers like Nexamp or ReVision Energy can lease land, build solar arrays, and sign up as many customers as they like but nothing is going to happen without the participation of local electric utilities. Without a connection to the grid, the electricity might as well not exist.

As originally designed, utility grids usually aren’t prepared for the intermittent surge of electricity from rooftop solar arrays and community solar farms. Often, utilities must upgrade equipment in order to handle the additional power, and that’s a potential problem for developers and their customers.

This became all too apparent earlier this year when Central Maine Power (CMP), the state’s largest provider of electricity, notified developers that it would revise interconnection agreements it had already signed with developers, threatening millions of dollars in solar developments. SunRaise Investments of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, had paid CMP $1.6 million in interconnection fees to cover a half-dozen new projects only to be informed by the company that it was working up new estimates for the engineering work on the grid, according to this article in the Portland Press Herald. Company executives were stunned.

Patrick Johnson, the company’s senior vice president for business development, told the newspaper: “It’s unprecedented for a utility to go back and change the price of upgrades. If we can’t rely on that, no one would move forward with a project.”

The utility later backtracked, blaming the problem on mid-level engineers who hadn’t consulted more senior executives. Some substations would need no upgrades, CMP said, while others could be reworked at a relatively low cost. What CMP had warned would cost hundreds of millions of dollars was chopped to about $40 million, and probably far less than that, CMP’s top executive told a legislative committee.

But the damage had been done, and lengthy interconnection delays remain a problem, not only in Maine but elsewhere.

“Definitely the interconnection problem is one we’ve heard of frequently,” said Larry Sherwood, president and CEO of the Interstate Renewable Energy Council (IREC), a non-profit that promotes clean energy nationally and consults on problems like CMP’s. “It frequently happens that states enact policies that encourage community solar installations, and then the utility doesn’t really have the capacity to review them and do the interconnect rules. That is a pretty common problem.”

Another issue is that a single developer pays for utility upgrades that actually benefit anyone else who wants to connect down the road. IREC has been working with regulators in Massachusetts and Maryland to encourage utilities to plan for more renewable energy over a longer period of time and then pay for the upgrades themselves. Every customer who connects would then pay a small fee to offset the cost, rather than having the entire burden fall on a single developer.

“If you want to have lots and lots of clean energy on the grid, you have to eliminate that bottleneck because it’s not going to work if the one customer has to pay,” Sherwood said. “If it’s uneconomic to do it, that means nobody is able to connect solar to that particular distribution grid until somebody’s willing to pay to upgrade it.”

One tool the IREC has developed is called Hosting Capacity Analyses, which provides information about a utility’s grid that can help developers place solar installations where they will not force costly upgrades or prompt complicated interconnection studies.

Not everyone likes solar development

Adding more renewables to the grid sounds like a slam-dunk these days but solar projects require undeveloped land, and that can be a problem for locals who resent the transformation of scenic views and environmentally delicate landscapes into industrial-sized solar farms.

Such was the case in Copake, N.Y., a town of about 3600 in rural Columbia County, where Hecate Energy planned to build a 500-acre solar farm, according to this account in The New York Times. After getting an earful from local residents about the size of the project, the company cut it in half, although Hecate said the electrical output would remain the same.

Copake was one of several New York communities that sued the state over a new law that made solar development easier. Although the suit was tossed out of court, the towns and the Audubon groups that filed it say they will appeal.

Similar disputes have popped up elsewhere. In the Mojave Desert, a group of activists is fighting a 3000-acre solar farm called Yellow Pine that will supply 500 MW of electricity to power 100,000 homes in California, according to The Los Angeles Times. Opponents note than more than 100,000 yucca and other plants will be destroyed, and an effort to move 100 federally protected desert tortoises to safer ground resulted in the death of about 30 of them.

“Is this really the way we want to do this?” asked Shannon Salter, a protester living near the site in Nevada’s Pahrump Valley. “Is this really green?”

Using land to support renewable energy and agriculture simultaneously is the idea behind projects developed by BlueWave, a Massachusetts-based solar developer and certified B Corp that specializes in “agrivoltaics.” One of its latest endeavors is a 4.2 MW project on a blueberry farm in Rockport, Maine, that it developed in conjunction with Navisun, an independent solar power producer. In a research plot covering half of the 10-acre site, panels are built over the blueberries to find out how well this traditional agricultural activity can coexist with solar production.

Founded in 2010, BlueWave has made dual-use solar arrays a cornerstone of its business model. Many of its projects are located in Massachusetts, which offers special incentives for dual-use projects. But, according to Managing Director of Solar Development Chad Nichols, BlueWave is expanding into other states in the Northeast that don’t necessarily offer financial benefits for agrivoltaic projects. Combining solar with agriculture can mean added development- and operating-related costs, but it’s also an incentive for communities and landowners who are hesitant about giving up productive land for solar.

Projects can be tailored to not only blueberry farming, but also to dairy, beekeeping, and sheep operations. Additionally, plants that have some shade tolerance, such as squash and pumpkins, are potential candidates for dual-use projects.

“It doesn’t have to be mutually exclusive,” Nichols said. “We’re not putting in parking lots or strip malls or housing developments. This is a low-impact installation that lends itself to either keeping land in agricultural production or maybe even putting into agricultural production land that wasn’t formerly. The sky’s the limit.”

He continues: “As a company, we’ve committed to a mission and philosophy that puts this squarely in line with our identify—of our regenerative goals as a B Corp, and how we can have a greater impact beyond traditional solar power. It’s that balance of understanding and respecting the land we’re working with.”

Making solar more affordable

One of the benefits of buying solar energy through a subscription is that it doesn’t require a big outlay of cash, opening the door to direct renewable energy purchases for more than the well-heeled. This is the aim of the National Community Solar Partnership, part of the Solar Energy Technologies Office in the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), which hopes to make affordable community solar available to every U.S. household by 2025.

The program provides free technical assistance, training, and other resources to community members, developers, and financial institutions. According to its website, the expansion of community solar would include 5 million households in the next four years and energy savings totaling $1 billion.

Although there is enough solar capacity now for 19 million households in the U.S., renters, homeowners without financing options, and those with roofs unsuitable for installing solar panels are being left behind. Community solar can reduce utility bills from 5% to 25%, according to NREL’s “Sharing the Sun” report, and getting to the $1 billion in savings goal would reduce an average bill by 20%.

The Community Solar Partnership had distributed $1 million for technical assistance as of October 2021, and hopes to grant another $2 million in the next year, according to the DOE. Projects don’t have to be huge. For example, a 400 kW project in the District of Columbia consists of just 829 panels, but it’s enough to help 100 households there cut their electricity bills in half over the next 15 years, according to a DOE announcement. By the end of this year, Washington’s D.C. Solar for All will have helped nearly 6000 income-qualified households reduce utility bills by 50%.

In the meantime, it’s full speed ahead for developers like Nexamp and ReVision Energy.

“Community solar opens up the floodgates for people who aren’t homeowners,” ReVision’s Bowie said. “That’s a really important part of our energy transition. There aren’t enough rooftops to be able to supply 100% of our energy needs, so community solar is a very important piece of the puzzle in our energy transition. It’s great that people are doing rooftop solar arrays but we will not get to where we need to be without community solar. You can’t do it on homeowners’ rooftops alone.”

Originally published on GreenBuildingAdvisor.com.

Scott Gibson is a contributing writer at Green Building Advisor and Fine Homebuilding magazine.