Deep-Energy Retrofit of an Old Timber Frame

Hudson Valley Preservation strips a late-1700s house down to its original timber frame, and salvages components from two major renovations in order to tighten up the building envelope for net-zero performance.

Built c. 1780, this timber-framed house sits on nearly 200 acres in Washington Depot, CT. The client purchased the property in November 2019, and it has been in the hands of Hudson Valley Preservation (HVP) ever since. The primary goal is to make it a net-zero-energy home. Because of its age and condition—not to mention six fireplaces—a deep-energy retrofit was the only way to get there.

The house was built using plank-frame construction methods. Originally, it had a timber frame with walls made of 1-1/4-in.-thick vertical oak planks running from sill to plate; the vertical planks were in lieu of studs. (This type of construction dates to the 17th century, and is most often seen in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire.) Here, the planks were nailed to the exterior of the timber frame; wood clapboards were used for exterior siding; and interior lath and plaster were applied directly to the planks. There were no wall cavities, and there was no insulation.

A major renovation around the turn of the 20th century got rid of nearly all of the planking. The carpenters added studs and built some interior walls on the first floor. Today, those walls and doors are relatively plumb, whereas nothing else is. In 1972, a second remodel concentrated on the second floor, and resulted in all of the partition framing that is there now.

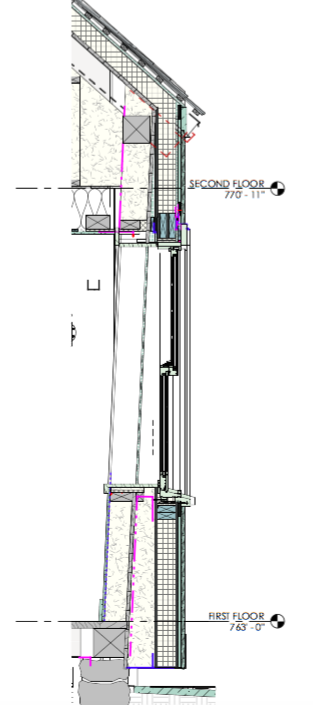

HVP Founder Mason Lord speculates there was some kind of event that made the house shift 4 in. to the north. To correct that, on the north and south elevations—the eave sides—HVP will add tapered studs to the exterior of the existing tongue-and-groove white pine−board sheathing. The idea is to shim the walls from 0 in. to 4 in. on one end, and vice versa on the other in order to plumb them up. This will create a second wall cavity—in addition to the interior wall studs—which they plan to fill with dense-packed cellulose. Lord notes that this unusual wall assembly was specified by Zero Energy Design, and should prove to be robust, performance wise.

The 12:12 slope roof was in good shape when HVP came onboard. (Strangely, portions of it had been reframed with 2x6s. Lord suspects the house had large shed dormers on it at one time.) The HVP crew added continuous beams to the inside of the rafters running from one gable end to the other, and they plan to fill the cavities with mineral wool. They will add exterior wood fiberboard insulation above the roof sheathing, and then run vertical wood strapping up the roof and cross strapping for nailing the new cedar shingles, creating an air channel beneath the roofing with vents at the eaves and ridge.

At some point more recently, closed-cell spray foam was applied to the interior of the basement foundation walls from the sill down 2 ft. HVP removed the foam at the sill timber beams—all of which were replaced—to allow it to dry to the interior. They plan to skin the exterior with 4 in. of Steico wood-fiber insulation, and they will create a 3/4-in. rainscreen, open at the top and bottom and covered with insect screening.

HVP is replacing the single-pane double-hung Brosco windows that went in during the 1972 remodel with flangeless Loewen triple-glazed double-hung windows with aluminum clad sash and Accoya 5/4×4 casings. They plan on using ThermalBuck for the window installation, though the details of how to incorporate it with the air and water barriers are still being worked out.

Squaring up and reinforcing the framing is only half the battle. Managing the envelope and choosing products to meet net-zero energy goals is another ball of wax. Lord points to six key considerations when tightening up centuries-old houses.

Ensure drying potential

Antique homes have survived largely due to their good drying potential. To ensure their continued survival, when improving the envelope, it’s critical to prevent water—in all its forms—from entering the wall, floor, and roof cavities. For this reason, Lord says it’s a good idea to use batt insulation, such as mineral wool or cellulose that can handle some moisture. He strongly advises against fiberglass; the batts that his crew uncovered were in a severely compromised state. (The house had blown-in cellulose too—likely added in the 1940s—and it was in much better condition than the fiberglass batts from 1972.) “Use mineral wool over fiberglass; it’s not hydroscopic, critters aren’t as drawn to it, and it’s a much better product for installing in uneven cavities. Plus, it’s harder to do a good job with fiberglass because it’s difficult to cut and box around outlets—and you really need to do a 100% good job with it.”

Create an air barrier

The plan for this house is to apply Majvest by Siga 500 SA, a self-adhered membrane, directly to the sheathing—walls and roof. This will put the air barrier as close to the conditioned space as possible, and allow the walls to dry to the interior. Asked about his product choice, Lord says it’s thicker than Henry Blueskin and has a comparable permeability rating but, more importantly, he can count on technical support.

Plan for good indoor air quality

Whenever tightening up an old home, measures must be taken to ensure healthy indoor air—particularly in houses that have centuries of dirt and other contaminants hiding in every crevice. Lord says installing a vapor barrier in basements and crawlspaces is a crucial first step, and he feels an ERV is the best choice for mechanical ventilation.

Steer toward electric

Though ideal, Lord says all-electric heating and cooling isn’t practical in most old houses if the goal is net-zero-energy usage—even with improved air-sealing and insulation. “For more efficient and cleaner energy, we have switched house systems from oil to propane boilers and furnaces, but it’s debatable on the embodied carbon side of the equation, as well as the overall cost since the BTUs produced by a gallon of oil are greater than per gallon with propane.” For this project, they decommissioned an oil-fired boiler, and will install two air-source heat-pumps and a Sanden hot water heater. A propane generator and an Esse Ironheart wood stove will serve as backup.

Perform multiple blower-door tests

Lord recommends a blower-door test be done after the air-sealing membrane is installed and again after the exterior fiber-board insulation is in—but before the clapboards are installed. He suggests another one be performed after the dense-packed cellulose has been blown in but before the wallboard is up. For this project, they will probably do another one after the plaster is done but before the trim is installed, though he recognizes there is less opportunity to make corrections at that point.

Choose products with reversibility in mind

“In the preservation world, it’s all about reversibility—whatever you do to an antique home should be reversible,” Lord says. He notes the push and pull between preserving old structures and improving their energy performance, illustrating the struggle by way of the product Grace Ice & Water Shield.

“It is so gooey that it becomes permanently adhered to all wood—whether plywood roof sheathing or 18th-century chestnut skipped sheathing. Roofs get changed every 20 to 30 years, so the shingles that stick to the top of the sheathing that is adhered to the Ice & Water Shield below make for a rough surface for the next shingling.” He sees the product as a good example of a nonreversible choice.

Similarly, he says, foam—whether rigid or spray—has less and less reason to be in old houses. “I’ve never felt good about foam use in old buildings. Maybe it was the words ‘reversible’ and ‘historic fabric’ niggling in the back of my mind. I was on the lookout for alternatives. It’s the same with fiberglass. It gets wet and sits and soaks on a 200-year-old oak sill beam below, creating more damage in a handful of years than the 200 years before.”

Originally published on GreenBuildingAdvisor.com. You can reach Kiley Jacques at kjacques@taunton.com. Photos and illustrations courtesy of Hudson Valley Preservation.