Deep Energy Retrofits Are Often Misguided

It’s time for energy retrofit specialists to overcome their prejudice against solar PV systems.

All through the 1980s and 1990s, a small band of North American believers worked to maintain and expand our understanding of residential energy efficiency. These were the pioneers of the home performance field: blower-door experts, weatherization contractors, and “house as a system” trainers. At conferences like Affordable Comfort, they gathered to share their knowledge and lick their wounds.

These pioneers understood what was wrong with American houses: They leaked air; they were inadequately insulated; they had bad windows; and their duct systems were a disaster.

Occasionally, these energy nerds would scoff at millionaire clients who were more interested in “green bling” — a phrase that usually described photovoltaic panels — than they were in reducing air leaks in their home’s thermal envelope.

A shared belief

What I’ve just described is (in anthropological terms) a set of beliefs associated with a distinct subculture. Our tribe had a shared belief: that improving a home’s thermal envelope is preferable to installing renewable energy equipment.

Occasionally, a few facts would appear to undermine our belief system. For example, if a disinterested observer noted that a proposed envelope measure had a very long payback period, most members of our tribe would answer that the measure was a wise investment, because energy prices are likely to skyrocket in the future.

During the waning years of the last millennium, these North American beliefs crossed the Atlantic and were adopted by a group of academics in Darmstadt, Germany.

The beliefs became petrified in a set of rules called the Passivhaus standard.

Times have changed

Several factors have changed since these beliefs were first formulated. For one thing, fossil fuel prices have stayed low; for another, photovoltaic equipment has gotten dirt cheap.

The (sometimes painful) fact is that it is now hard to justify many energy-retrofit measures that energy experts still eagerly recommend. Moreover, solar bling now has a fast payback.

In short, the world has turned upside down.

The collapse of the deep energy retrofit movement

The first deep energy retrofit occurred in 1982, when Rob Dumont and Harold Orr lopped off the roof overhangs of a ranch house in Saskatoon. Interest in deep energy retrofits has waxed and waned since then; the movement had a mini-revival three or four years ago.

Even though true believers still hope to see millions of homes undergo deep energy retrofits, at this point the movement is dead in the water. The cost of these jobs is unjustifiable.

Even back in 1982, Dumont and Orr were far from enthusiastic proponents of the deep energy retrofit approach. In their report on the Saskatoon retrofit experiment, they wrote, “Without question, there are many instances in which economics, based on a cost-benefit analysis, would not support the application of [the chainsaw retrofit] measures described here.”

Expensive and risky

The point was further driven home at a presentation given by Paul Eldrenkamp and Mike Duclos at the recent BuildingEnergy 14 conference in Boston. Eldrenkamp is a remodeling contractor, and Duclos is an energy consultant; their presentation was titled, “Three Deep Energy Retrofits, Three Years Later.”

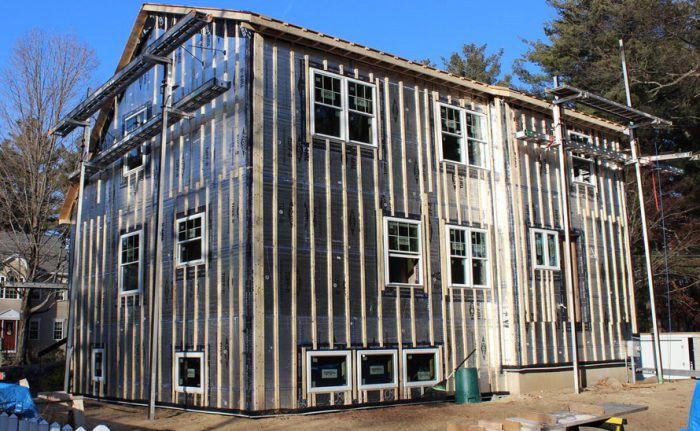

Endrenkamp shared detailed cost information on one of the three projects he discussed: a 5,600-square-foot duplex in Belmont, Massachusetts. The cost of the project’s energy-related work was $258,000.

Eldrenkamp noted that the payback period for many deep energy retrofit measures is quite long. He pointed out, for example, that when a designer specifies 4 inches of polyiso for exterior walls, the last 2 inches of polyiso has a payback period of “maybe 160 years.”

He also noted that it’s very hard for a remodeling company to make any money on this type of work. “These projects are really expensive and really risky, and I don’t think they are a terrific business model,” said Eldrenkamp. “I feel no confidence that deep energy retrofits will get us very far in terms of the challenges we face. We have to come up with other tools. We have to make sure that our new buildings make sense; most of our new buildings make no sense.”

Summing up, Eldrenkamp said, “We can’t do it with deep energy retrofits.”

Then Duclos chimed in: “We need to look at low-hanging fruit like lights and appliances.”

And Eldrenkamp responded, “Right. And focus on occupant behavior. And then install PV.”

The argument in favor of PV keeps getting stronger

This isn’t the first time that I’ve pointed out that installing a PV system makes more sense than investing in a deep energy retrofit. I wrote an article on the topic in 2010 (“Energy-Efficiency Retrofits: Insulation or Solar Power?”) and another article in 2012 (“The High Cost of Deep-Energy Retrofits”).

Every time I write about the topic, I realize that the economic argument has become even more compelling that the last time I looked into it. Natural gas has gotten cheaper; so have PV modules.

Overcoming our prejudices

There’s a moral to this story. It’s aimed at the tribe I belong to: the energy nerd tribe. It’s time that we faced up to our prejudices — especially our prejudice against solar equipment.

If you’re giving advice to middle-class homeowners who hope to lower their energy bills, start with an energy audit. Once you’ve done the audit, run the numbers.

Assuming the house has an unshaded south-facing roof, it’s probable that the best energy-saving measure will prove to be the installation of some solar bling.

Two counterarguments

I anticipate that some readers of this blog will disagree with my conclusions. Here are two likely counterarguments:

Today’s net-metering contracts are likely to change, so the payback period for PV is about to lengthen. This issue is political, not scientific, and it is clearly impossible to predict which way future political winds will blow. Nevertheless, I feel that any upcoming changes to net-metering contracts won’t be significant enough to fundamentally change the direction of current trends regarding PV payback.

For more perspectives on this issue, see The Big Allure of Cheap PV, including the discussion in the comments posted at the bottom of the page.

It doesn’t matter what it costs to perform a deep energy retrofit; we need to cut down on carbon emissions to save the planet, even if our efforts are costly. Of course, any homeowners who are committed to reducing their environmental impact are free to invest in a deep energy retrofit if they want, even if the payback period is 100 years or more. But from a policy perspective, such investments make little sense.

If a government wanted to create an enlightened environmental policy aimed at reducing carbon emissions, it wouldn’t invest in deep energy retrofits. (Sadly, very few national governments are interested in reducing carbon emissions, but that’s a topic for another blog.) There are countless examples of low-hanging fruit that could be picked if we wanted to develop better incentive programs to achieve carbon reductions: we could increase our investments in low-income weatherization programs, for example, or create better programs aimed at improving vehicle fuel efficiency or phasing out coal-fired power plants.

Deep energy retrofits don’t appear anywhere near the top of such a list. From a policy perspective, every billion dollars spent on a low-yield carbon reduction measure is a billion dollars that isn’t available to invest in a more logical approach to carbon reduction.

Originally published on GreenBuildingAdvisor.com.