Energy-Smart by Design

Building orientation, passive-solar design, and a radiant-barrier roof are key to energy efficiency in a hot-humid climate.

Synopsis: Controlling solar radiation and addressing infiltration of outside air are priorities when designing for a hot-humid climate. This contemporary home capitalizes on natural ventilation, with a radiant-barrier roof system that works efficiently in all climate zones.

This contemporary “farmhouse” is located in the booming urban hub of Central Austin, Texas. It belongs to an older couple whose objectives in having it built included downsizing from a much larger suburban home, reducing their carbon footprint, and living a more pedestrian-oriented lifestyle. To that end, they charged Barley & Pfeiffer Architecture with designing a comfortable, healthy, and resource-efficient house that would blend into the neighborhood of small-scale post-World War II homes.

Principals Peter Pfeiffer and Alan Barley have been designing high-performance homes in Texas’s hot-humid climate for over 30 years. Their projects commonly include metal roofing, deep overhangs, awnings, and other shading devices, as well as a combination of fiber-cement lap siding and locally sourced limestone veneer. Their intention is always to design energy-smart structures that rely most heavily on site orientation and passive-solar design and natural ventilation rather than HVAC systems. They also place great emphasis on good indoor-air quality. Peter’s ventilated radiant-barrier roof system is chief among their design strategies. It took 40 years to develop, and this house is the beneficiary of his decades-long research.

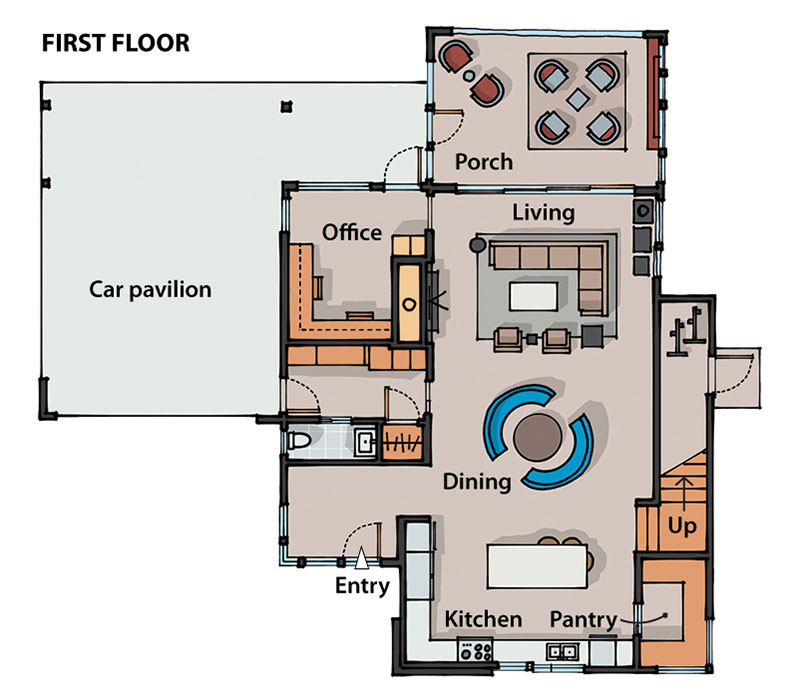

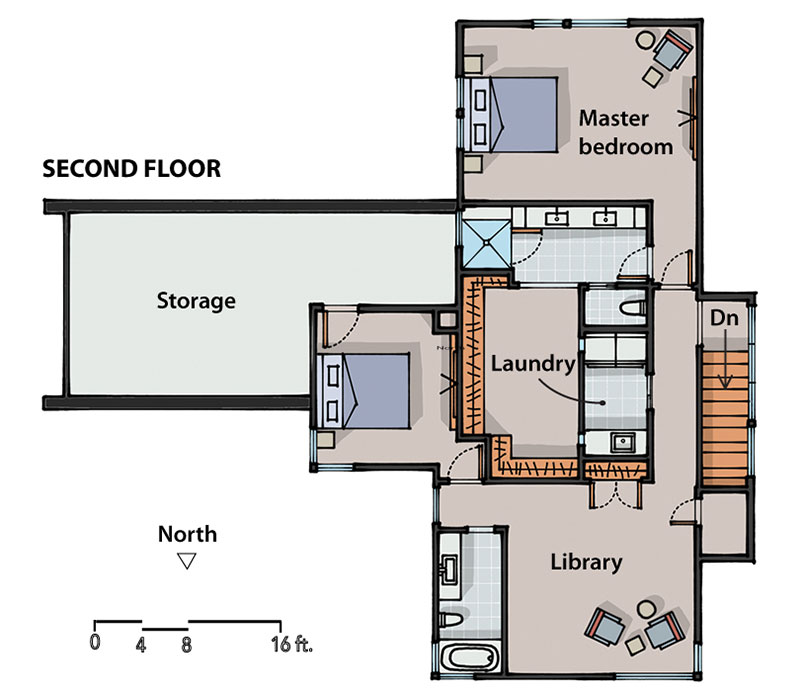

Two floors are better than one

The north-facing lot measures just 60 ft. wide by 96 ft. deep. To accommodate the desired volume of living space, they needed to build up rather than out, which has benefits in a hot climate. First, because roofs are a major source of solar gain, decreasing a roof’s size relative to the building’s volume reduces that gain. They advise clients to put the money saved by shrinking the roof surface into better building materials. Second, it minimizes the perimeter and interface between the wall system and the foundation slab, which is notoriously vulnerable to air infiltration—a major consideration when seeking to curb energy usage. “More house over less foundation is a more efficient house to build per square foot,” Peter says, adding that building up rather than out also means less impervious coverage, which helps with storm water management. Plus, a stacked, compact house with an air handler at the center supports shorter duct runs, which further reduces energy consumption by decreasing losses to friction along the ducts.

Oriented for cooling

To block unwanted solar gain, the house is primarily closed to the west. Conversely, to capitalize on prevailing breezes, the living room and screened porch face south-southeast. The master bedroom is farthest from the street on the second floor, and acts like a screened porch with windows on three sides for optimal natural ventilation.

|

|

SPECS

Bedrooms: 2

Bathrooms: 2-1 ⁄ 2

Size: 2450 sq. ft.

Location: Austin, Texas

Architect: Barley & Pfeiffer Architecture,

barleypfeiffer.com

Builder: Risinger Homes,

risingerbuild.com

Cooler from the start

Energy demands can be mitigated right off the bat by correctly orienting the house on the lot. “A house should be inherently energy efficient without reliance on mechanical systems,” Peter notes. “You can get 10 times more out of your house by designing it to respond to the climate.”

This house is sited to be shut off to intense western sun and open to south-southeasterly breezes. To help capture those breezes, Alan says houses in this climate should try to incorporate screened porches and connected outdoor living areas. Come winter, the house shields those spaces from northwesterly winds, making them more comfortable. By adding fireplaces to screened porches, they can be used nearly year-round. The porch on this house not only takes in the prevailing breezes, it also works in sync with the stair tower, which acts as a passive-thermal siphon to draw warm, moist air up and out upper-floor windows. “Enhanced natural ventilation for homes in the south is becoming vogue again,” Peter says, “as people are becoming more and more aware of indoor-air-quality issues.”

Another of the architects’ preferred strategies is putting all of the bedrooms on the second floor and using two separate air-conditioning systems, one for each floor. This makes for a more energy-efficient home because mechanical cooling

can be targeted depending on time of day and occupant location. “It is better to have the redundancy of two separate systems that are sized only for the load they’re handling,” Peter explains. “One system for two floors is never right, and then you have an oversized system running one part of the house or another.”

For Peter and Alan, the main priorities when designing for a hot-humid climate are addressing infiltration of outside air and controlling solar radiation. This house has 2×4 walls with closed-cell spray foam that acts as an air barrier and controls humidity; the attic is unvented while the roof above it is vented to remove water vapor and improve the roof’s thermal performance. Heat gain is further addressed with calculated shading of the windows using 30-in. overhangs

and awnings. Additionally, the tight building envelope is positively pressured; negative pressure taxes cooling equipment and brings in dust and other contaminants that reduce indoor-air quality. Their general approach is to bring outside air into the house by way of either a mechanical system like an Ultra-Aire conditioning unit or a barometric damper that opens when the house pressure goes below neutral. This allows fresh air into the return-air chamber; it is then filtered and dehumidified.

Ventilated radiant-barrier roof

Peter’s roof design is paramount among his firm’s cooling strategies. It uses unpainted galvalume, which he says thwarts about 72% of the radiation that hits it. That means only a small percentage of solar radiation penetrates through to the space below. Lifting the metal roofing off the sheathing with diagonally run furring strips—spaced 24 in. o.c. with 3-in. gaps between the board ends—creates a 3 ⁄ 4-in. gap from soffit to ridge for continuous movement of air through the ridge vent. The underside of the galvalume works like a foil-faced radiant barrier, so little absorbed heat is transmitted into the attic. The metal roofing also dissipates heat quickly at night, which means it is not radiating heat inward. To create an additional barrier to heat, the area between the rafters is sprayed with closed-cell foam. In short, it is a system to mitigate solar heat gain, thereby keeping the sealed attic space below as cool as possible.

A builder’s take

Matt Risinger, the builder on this project, included Peter’s radiant-barrier roof on his first spec house and has been using it ever since. He is sold on its efficacy, although he prefers Zip System sheathing because the roof-deck seams can be taped and the flexible flashing works well on plumbing penetrations. In terms of constructability, because the roof is up on 1x4s, roofers have toe boards across the entire surface. One consideration for general contractors that Matt notes is determining whether the framer or the roofer should install the furring. What else do builders need to know? It’s pricey—all of those 1x4s add up—and it’s important to be cautious about underlayments and penetrations. There are potentially two layers of flashing, and penetrations in the roof decking create air gaps. If they are not flashed at the roof deck and water gets through, there could be a leak that goes undetected.

One house among many

After decades spent fine-tuning both passive and active systems for dealing with Texas heat, Barley & Pfeiffer Architecture has a large collection of low-energy, maximum-comfort homes to their credit. This home is young among them. Peter makes a final and noteworthy point: Resiliency in Texas looks different than it does in cold climates. This last winter aside, the state’s power system is typically most vulnerable during the summer and hurricane season; plus, the region is dealing with temperatures that average 10°F to 20°F warmer than two decades ago. Handling heat is a bigger threat than going without. Nonmechanical cooling strategies that function independent of the grid are imperative. As this house testifies, he and Alan have it pretty well dialed in.

—Kiley Jacques is senior editor at Green Building Advisor.

Photos: Ryann Ford

Floor-plan drawings: 07sketches/Bhupeshkumar M. Malviya.

From Fine Homebuilding #301

To read the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.

RELATED LINKS