Net-Metering Is How Most Solar-Powered Homes “Store” Electricity

Homeowners who install solar panels can get credit or money from their utility company for the power they send back to the grid if their state has net-metering rules in place.

A steady decline in the cost of photovoltaic panels has made solar energy more affordable for many U.S. households. PV is now in the neighborhood of $3 per installed watt, 65% lower than it was a decade ago, according to the website EnergySage. Prices are almost certainly headed lower yet.

Two other incentives also have helped nudge homeowners toward installing solar. One is a 30% federal tax credit, which is currently due to begin falling in 2020 on the way to a complete phaseout in 2022. The other is net-metering, an accounting system in which solar customers are billed only for the net amount of electricity they use during a billing cycle.

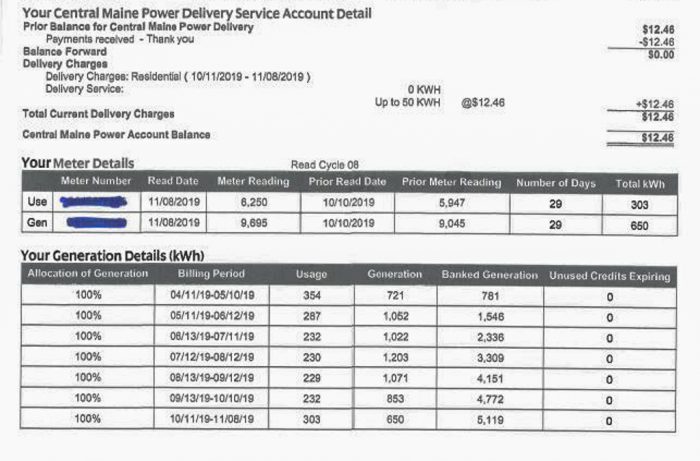

At times, residential solar systems are likely to generate more electricity than the homeowner needs. In the summer, for example, long days and plenty of sunlight typically mean excess generation for those living in climates where AC isn’t always needed. In winter, the opposite is true. Panels don’t get enough sunlight to meet household needs because there isn’t as much sunlight and demand for electricity is higher.

Net-metering is a way of evening out demand and production. When there’s an excess, homeowners get a credit on their bills. When the panels aren’t producing enough juice, the homeowner buys electricity from the grid to meet demand. Customers end up paying for their net energy use, hence the name.

Plans vary from state to state

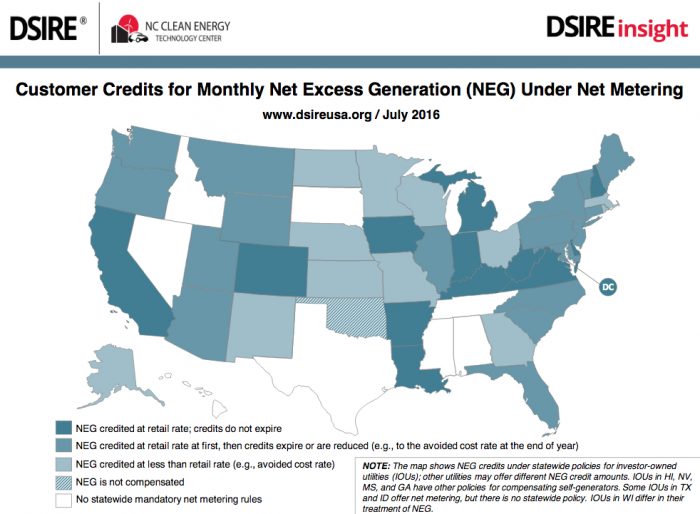

But there’s a catch. Unlike the income tax credit, net-metering is a creature of state governments and electric utilities, not the federal government. Most, but not all, states have net-metering on the books, and there is a great deal of variation in how net-metering reimbursements work, as the Solar Energy Industry Association explains on its website.

The North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center, part of North Carolina State University, maintains a state-by-state database of net-metering policies called DSIRE (you can have a look here). The database is extensive, covering much more than net-metering alone. To speed up your search, look for “net metering” in the Policy/Incentive Type field after you’ve plugged in the state where you live.

Net-metering makes sense for homeowners, but it has proved controversial in many parts of the country. A key question is how much homeowners are reimbursed for the excess electricity they send to the grid: the full retail rate (what they pay for the power they buy from the utility) or some lesser amount, such as the wholesale rate or the “avoided cost” of the power.

Additionally, how the banking system works can have a lot to do with how homeowners benefit. During the summer, a solar customer may build up a surplus of power credits that would be useful during the winter when power production drops off. But credits may not be carried forever. The point at which the utility resets the clock and zeroes out the account determines whether the customer earns back all of the excess or leaves some of it on the table.

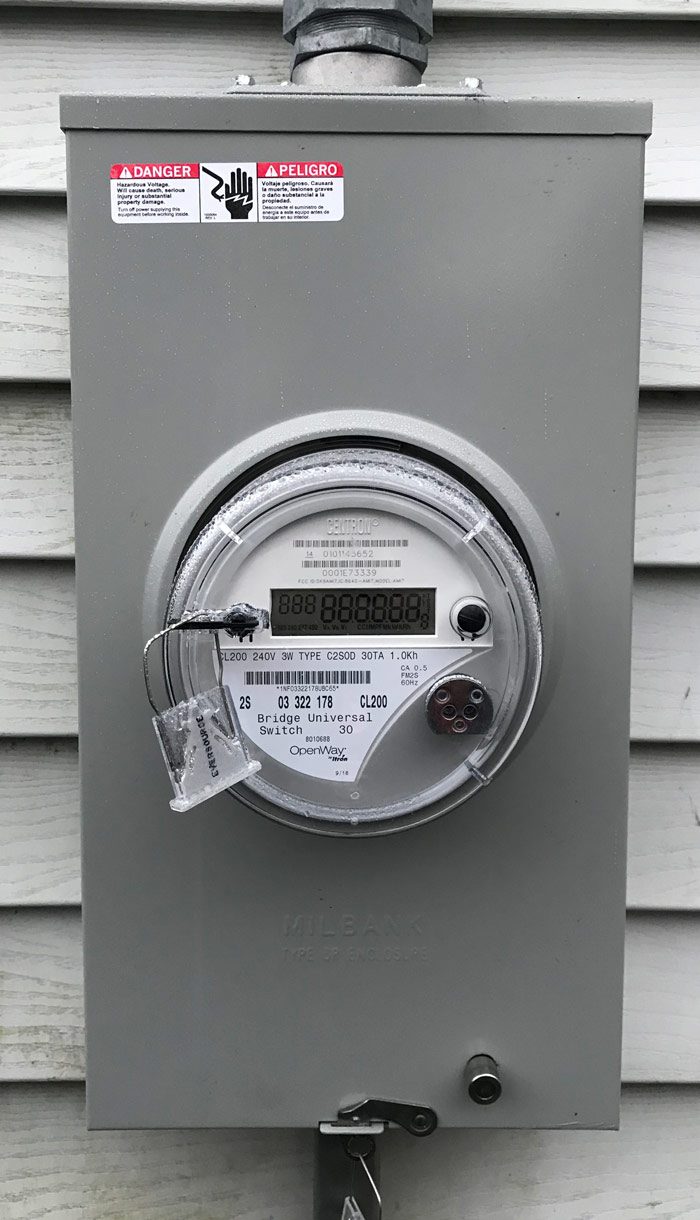

Brian Lips, senior policy project manager at the Clean Energy Technology Center, says these rules vary considerably around the country. Credits may be rolled over to the next month indefinitely, or zeroed out every month. In some states, customers get some money for unused credits while customers in others don’t get anything. Net-metering customers may have two-direction meters that track both power exports and incoming grid power, while in other jurisdictions solar customers have to separate meters that track generated power and incoming power. In short, as the map below indicates, there’s little uniformity to net-metering rules around the country.

These variations are what public utility commissions and state lawmakers all over the country have been grappling with. Critics complain that net-metering rewards well-heeled consumers who can afford to put up solar panels in the first place, not the average-rate payers who end up subsidizing solar. They also argue that solar customers are essentially freeloaders who benefit from the grid but don’t pay their fair share to maintain it.

Advocates counter that net-metering allows homeowners to recoup the cost of their PV systems. There also are benefits to the grid, including less need for conventional generating plants that run on oil, coal, or natural gas. That reduces the number of new plants that must be built to supply electricity, as well as the hours of operation of “peaker” plants that run only when demand is high. These factors mean cleaner air and a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, a benefit to all of society.

What’s ahead?

The situation is not static because solar technology as well as public policy continue to evolve. Battery prices are falling, making storage another option for managing excess electricity production. Utilities are experimenting with interactive systems that permit grid operators to tap into residential batteries, for a fee. Green Mountain Power, a Vermont utility, and Tesla have developed such a system using Tesla’s Powerwall batteries.

As Carlos Huerta describes in this Green Building Advisor guest blog, there may be other means of compensating solar customers for the excess power they generate. Hawaii, for example, eliminated net-metering in 2015. In its place are two other programs that make use of smart-grid features to pay customers for the electricity they provide to the grid.

And there may come a day when advances in solar technology make the equipment smaller and much less expensive, to the point where there’s no point in metering solar electricity at all. Dana Dorsett, a frequent GBA contributor, put it this way in a comment about Huerta’s blog:

“Unlike the unfulfilled early promise of nuclear, the future of PV eventually will become too cheap to meter even on incremental improvements.” But, he adds, don’t look for that kind of change in the near term.

More about solar-powered homes

How it Works: Grid-Tied PV Systems – Most photovoltaic (PV) systems are tied to the power grid, which means that any surplus is fed back into the grid, and any deficit is supplied by the grid.

Installing Rooftop PV – Get a detailed overview of how homes are evaluated for solar, how a photovoltaic system works, and how it’s installed.

Is Solar Power the Solution? – Solar panels might be a wise investment in light of a generous federal tax credit set to expire by the end of 2019.