The Associated Costs of Installing a Ductless Minisplit System

It’s important for builders to educate clients about the related expenditures of minisplits—it’s not just about the price of indoor and outdoor units.

By Jon Harrod

The ductless heat pump market is becoming highly competitive. As established contractors, we sometimes find ourselves bidding against small operators willing to install equipment for little more than wages. We also face pressure from customers who browse equipment prices online, then use this information to question our bids. (The apparent mismatch between equipment price and installed price has prompted some lively discussion on this site; see “Are Ductless Minisplits Overpriced?”) In order to remain competitive while still earning a fair profit, it’s important to understand and manage the true costs of a ductless installation.

When customers price out equipment online, they usually look up minisplit indoor and outdoor units, but ignore—or at least underestimate—the “balance of system” (BOS), which is the other equipment and materials required for a fully functional installation. I first learned the acronym BOS from friends in the photovoltaic industry, where it’s used to refer to items like mounting racks, wire, conduit, and inverters—everything except the PV panels themselves. As the price of panels has plummeted, BOS components make up an ever larger portion of a PV system’s costs.

I have no reason to think that the cost of ductless equipment will be falling any time soon. In fact, the trend seems to be in the opposite direction; we recently got notice of double-digit price increases from one of our suppliers. Nevertheless, as I’ll explain below, the costs of BOS components are well worth paying attention to.

In a typical ductless minisplit installation, BOS may include:

- Electrical components (circuit breaker, line voltage wires, communication wires, disconnect, whip, and surge suppressor, plus small parts like cable clamps and ring connectors)

- Mounting and protection for the outdoor unit (sling or stand, gravel and/or pad; some sites may also require a snow shield or wind baffle)

- Line sets and line set covers and associated items like insulation tape and wall sleeves

- Condensate removal components (piping and sometimes a condensate pump)

- Auxiliary controls (remote thermostats, WiFi adapters, and pan overflow switches)

- Miscellaneous consumables (sealants, zip ties, fasteners, nitrogen, and refrigerant)

A case study

I did a deep dive on BOS costs for an example single-zone system of the type my team installs every day. The one-ton outdoor unit is mounted on an 18-in. steel stand set on a base of compacted gravel in a “sandbox” built of pressure-treated 2x4s. The indoor unit is mounted on a first-floor exterior wall. The units are connected by about 22 ft. of insulated line set and 18 ft. of line set covers plus fittings. The installation also includes a new 15A circuit run through the basement, a whip and disconnect, and a surge suppressor. Condensate drains by gravity to the outdoors through PEX tubing.

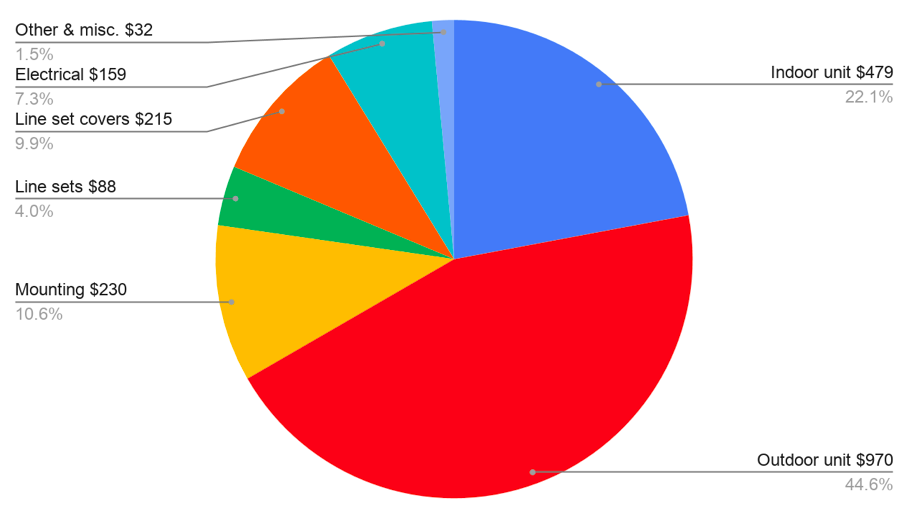

I priced out all system components and consumables, down to staples, zip ties, and a quart of vacuum pump oil. Even in this no-frills installation, BOS makes up a third of the total equipment and materials costs. The breakdown is as follows:

- The outdoor and indoor units are the most expensive items, at 44.6% and 22.1%, respectively.

- The largest BOS categories are mounting hardware and materials (10.6%), line set covers (9.9%), and electrical components (7.3%).

- Line sets (4.0%) and miscellaneous materials (1.5%) account for a smaller portion of total costs.

These findings are consistent with other job costing I’ve done on ductless systems. In more elaborate installations, with longer line sets, snow shields, condensate pumps, and auxiliary controls, BOS costs can edge closer to 40%.

How to use this information

Heat pump contractors can use this understanding to increase profitability in several ways:

Pricing and ordering: Just the awareness that BOS costs are nontrivial can help to ensure that they are properly accounted for. Prices for some components like copper line sets fluctuate with commodity markets; it’s important to make sure these are kept up to date. And don’t hesitate to periodically revisit products and vendors and do some comparison shopping.

Design: Thoughtful design can help reduce BOS costs. Placing outdoor equipment as close as possible to indoor units (while still observing minimum line set requirements) reduces line sets and line set covers and possibly the amount of refrigerant needed as a trim charge. It can also save labor and increase system output/efficiency. Optimal placement becomes especially important on multi-head systems, which typically involve longer, more complicated piping runs. Routing line sets through unfinished basements and attics can reduce both the cost of line set covers and their visual impact on the exterior facade.

Installation and materials management: Installers and shop managers play an important role in containing BOS costs. I explored material waste reduction as a profit center for insulation work in a 2009 article in Home Energy Magazine, and many of the same findings apply to ductless BOS. Line set and control wire cutoffs longer than 10 ft. or 12 ft. can be saved for use on future jobs. Partial line set covers and shorter lengths of line voltage wiring can also be set aside for later use. Critical to efficient use of remnant materials is a good system for storing and organizing them in the van and back at the shop.

I have gone back and forth on the question of whether to purchase line sets in pre-cut lengths (our vendor stocks 15 ft., 35 ft., and 50 ft.) or to buy 150-ft.-plus rolls and cut off material, as needed. The same applies to pre-made electrical whips versus rolls of THHN wire and flexible conduit. On one hand, purchasing these materials in bulk reduces the amount of unusable cutoffs and may yield better unit pricing. On the other hand, the larger rolls take up valuable van space, and use of bulk materials makes it harder to allocate the cost of a purchase to individual jobs.

Sales: In addition to preventing oversights and errors in estimating a job, awareness of BOS costs can help salespeople build trust and value with customers. Explaining BOS to the customer who priced out equipment online can help them better understand the full cost of the job. This conversation also provides an opening for the salesperson to differentiate their bid from those of competitors by highlighting the inclusion of “best practice” BOS components like wall sleeves and surge suppressors.

Competition and innovation: Some ductless BOS components are frankly overpriced. A single 6-ft. length of the PVC line set covers I use costs as much as several 12-1/2-ft. lengths of vinyl siding. An 18-in. stand, at around $160, costs as much as a box-store bicycle with moving parts and a nicer paint job. With the ductless minisplit market booming, there’s clearly room for competition and innovation in this space.

A new frontier

My colleague Hal Smith at Halco Energy has developed some interesting approaches for reducing BOS costs (full disclosure: my company, Snug Planet, is in the process of joining forces with Halco Energy). Hal’s team has begun fabricating heat pump stands using plastic condenser pads, 12-in. plastic risers, and threaded steel rods; the cost is roughly half that of a steel stand. The stands are fabricated in the shop to match the dimensions of the outdoor units, saving assembly time in the field. Hal’s shop has also begun producing attractive snow shields custom-made for the heat pumps they install.

I sometimes remind my team that net profit comes down to a small difference between two large numbers. For a contracting company to grow and prosper, it needs to bring in about 10% more in revenue than it spends on materials, labor, and overhead. That translates to $600 on a $6000 ductless job. A hundred dollars saved on BOS components—doable with good planning and attention to detail—can have an outsized impact on the bottom line. Or, if you choose, you can pass the savings on to customers in the form of a more competitive price.

________________________________________________________________________

Originally published on GreenBuildingAdvisor.com. Jon Harrod is founder of Snug Planet, a contracting company in Ithaca, N.Y., whose mission is to reduce building energy use in ways that make sense for people and the planet. Jon holds multiple certifications from the Building Performance Institute and has published numerous articles on energy efficiency and green building. Photos courtesy of author, except where noted.