Easy, Elegant Mantel

Build a fireplace surround from one sheet of MDF and some stock moldings.

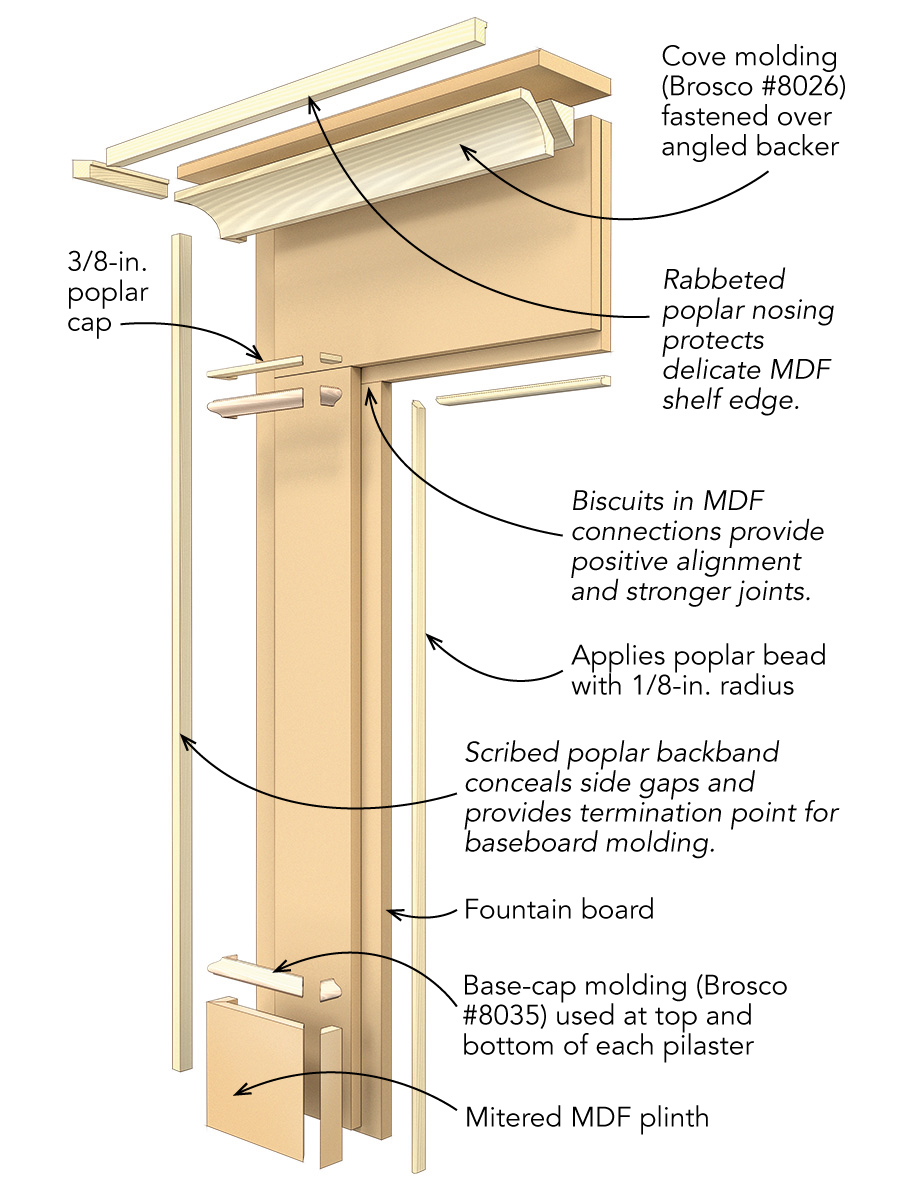

Fireplace surrounds—better known by the more commonly used term mantels—are a finish carpenter’s playground. They’re a relatively small, cleanly contained opportunity to create a centerpiece that shows off our craftsmanship, lets us exercise our eye for proportions and design, and, for better or worse, gives us a chance to pile on the moldings. But not every mantel job has a big budget, and that often leads to unimaginative design and execution, or worse, a cookie-cutter, factory-produced, prefab option. But with a bit of creativity, even a modest-budget living room can be finished with an elegant fireplace surround. All you need to build the mantel shown here is about $125, enough for a sheet of 3/4-in. MDF, some 1x poplar, and a couple sticks of stock molding.

As far as trim-carpentry projects go, this one is fairly straightforward. The work can be done in a shop, as it was for this project, or right on site. The tools aren’t specialized, and in most cases can be chosen based on what is already in your arsenal. For instance, I’d be just as comfortable joining boards with floating tenons as I was using biscuits, and even though I used a tracksaw to cut the MDF parts, a well-tuned tablesaw would also work.

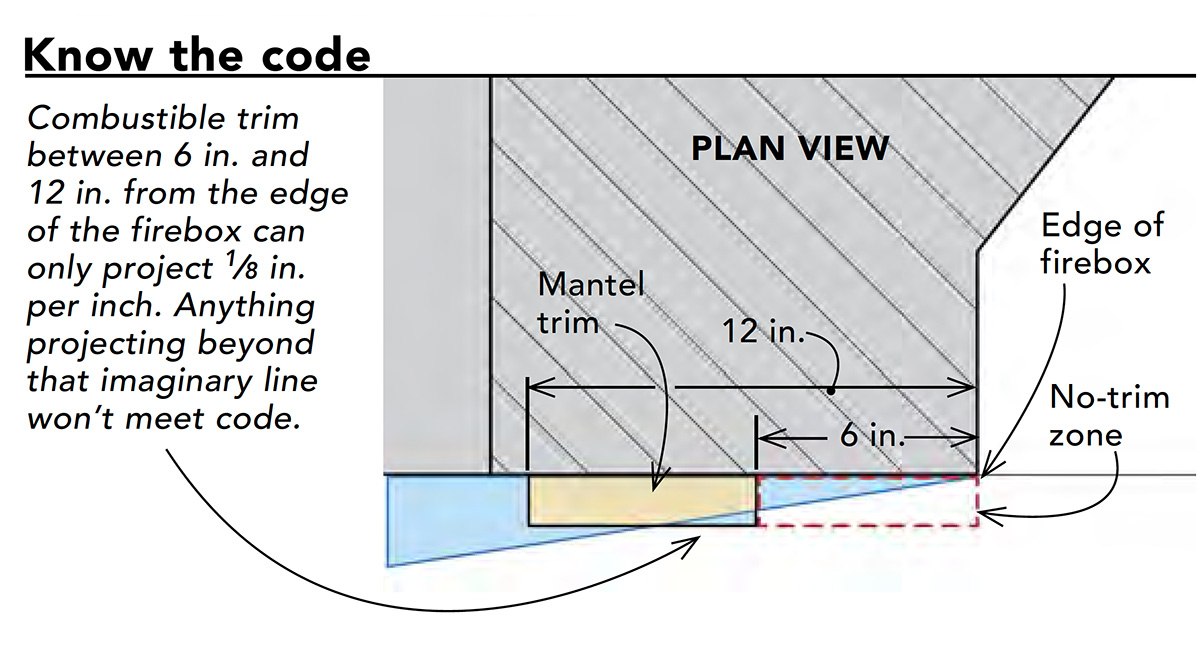

The dimensions of the assembly shown here are based on a simple Federal design by woodworker Mario Rodriguez, which appears in his excellent book, Building Fireplace Mantels. I scaled the parts and customized the assembly to fit the room where the mantel was installed, but before you go too far down the path of designing, it’s important to consider the restrictions of the building code.

The code is not difficult to satisfy, but fireplaces in old houses don’t always mesh with modern code standards. The problem is that the masonry around the firebox often isn’t wide enough to accommodate a mantel that’s set far enough away from the firebox to meet code—at least not without cartoonish proportions.

Luckily, the fireplace in this house is nonfunctional, and the homeowners simply wanted a decorative surround as a focal point. But if the fireplace had been operational, I would have scaled up the entire surround to maintain the mantel proportions, and then covered the brickwork with slabs of stone or tile that extend onto the surrounding drywall as far as necessary to cover the gap between the firebox and the mantel foundation boards. Finally, keep in mind that clearance rules for manufactured fireplace inserts and stoves supersede the building codes, and may be stricter.

Start with a solid foundation

The foundation boards of this mantel have two roles. First, they create a visual backdrop for the entire fireplace surround, helping to ground the design. Second, they act as a flat, plumb surface in an assembly that is rarely so. This allows the rest of the parts of the mantel to attach regardless of the condition of the wall.

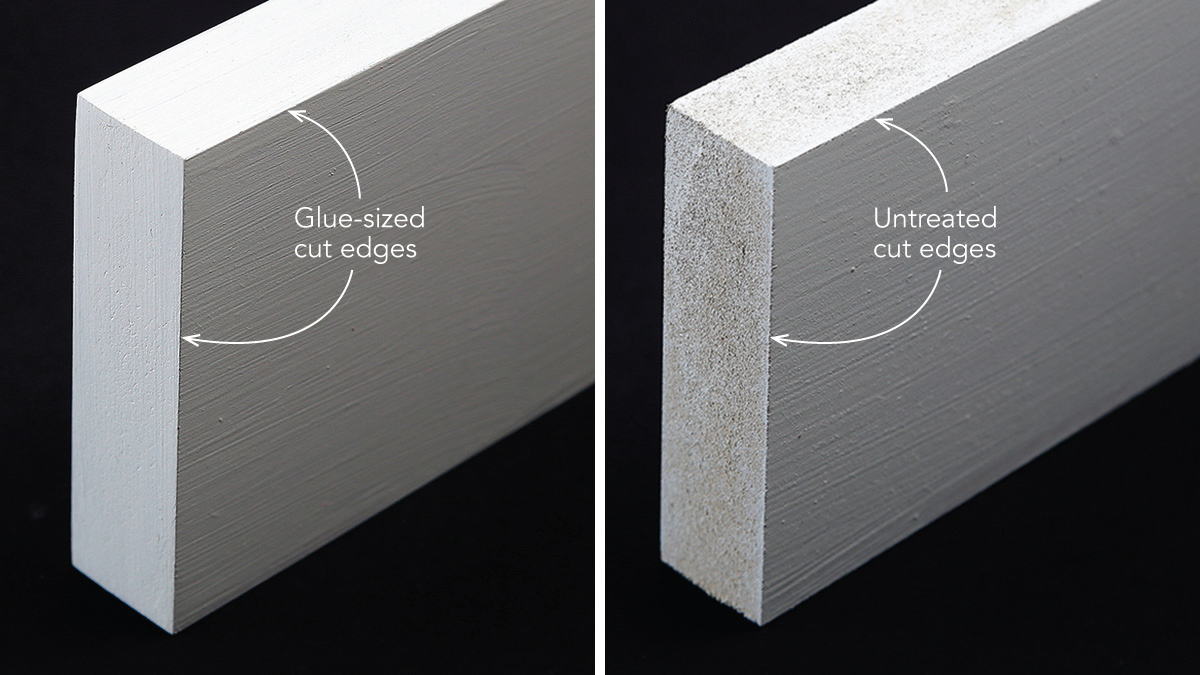

Glass-smooth edges in MDF

One of the downsides to working with MDF is that, if left untreated, the porous fibers exposed by sawcuts are difficult to finish smoothly. I used to rely on spackle to smooth these problematic edges, but more recently switched to glue-sizing the edges instead. Glue-size is essentially watered-down yellow glue that’s brushed or rolled onto the edges of the board, where it soaks into the wood fibers and hardens. I find that a couple of passes with this watery glue solution (allowing for dry time between coats) followed by light sanding, then shellac-based primer, will result in a surface that’s smooth to the touch.

An easy fit, even on wavy walls

At just 3/4 in. thick, the foundation boards don’t leave room for scribing to meet the wall. Instead, focus on getting the foundation boards plumb and in plane with each other, then cover the gaps with a scribed shelf on top and backbands on each side.

Moldings make a finished mantel

Moldings can be mitered and fastened to the mantel piece by piece, but preassembling them is a better approach. When the focus is on joining each piece of molding to another rather than to a substrate, you end up with strong assemblies that behave as a unit, reducing the chance that miters will open up over time.

Check out a video related to this article: Scribing Made Simple

From FineHomebuilding #273