Selecting Paint-Grade Interior Trim

Learn the pros and cons of common trim materials to choose molding that looks good and finishes well.

Synopsis: Shopping for interior trim can be an overwhelming chore. The array of products made of different materials can leave even experienced builders scratching their heads. FHB associate editor Chris Ermides takes a look at today’s world of interior trim, including finger-jointed, medium-density-fiberboard, and synthetic trim products. Each style is profiled and includes a list of pros and cons. This article includes a sidebar about flexible moldings, which can be useful on curved walls or arched openings.

Magazine extra: Take a tour inside The New England Woodworking Company’s millwork shop, and learn how custom and replacement-molding profiles are shaped on their computer-aided cutting equipment.

If you’re reading this website, you probably love wood. Like it or not, though, when it comes to painted trim, the alternatives to solid wood can make more sense. Finger-jointed, medium-density-fiberboard (MDF), and synthetic trim come with primer coats applied at the factory, which saves you a load of time and trouble. But choosing among these three materials isn’t easy.

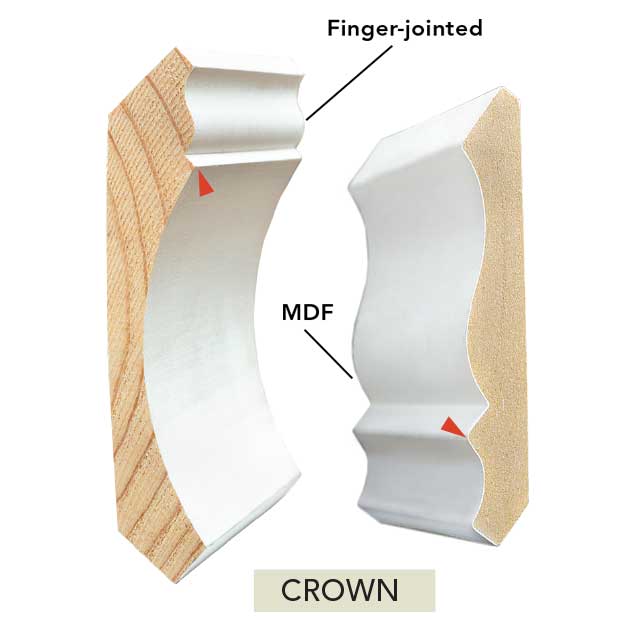

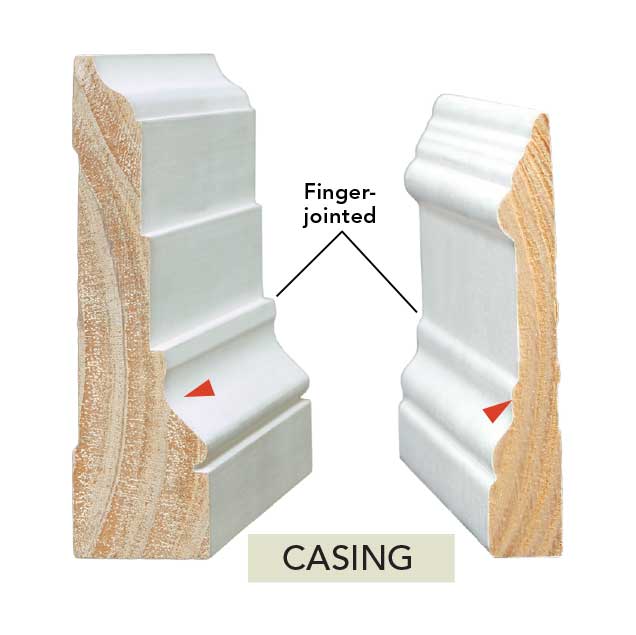

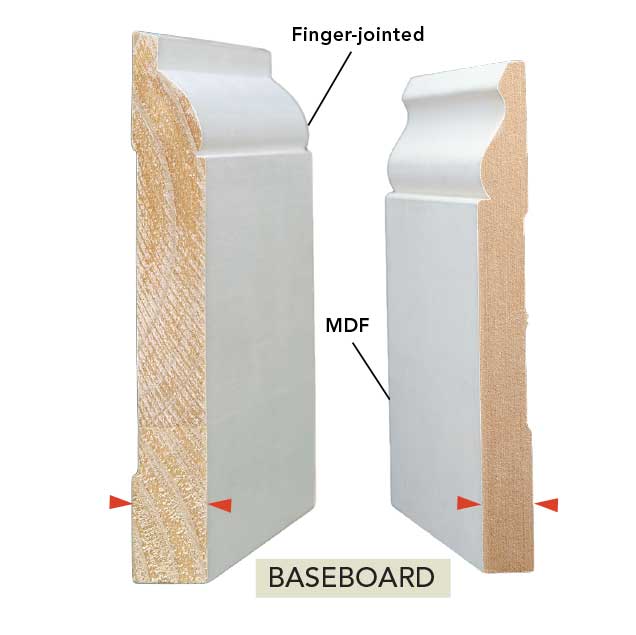

Finger-jointed trim is knot-free, but it can be pricey. MDF is inexpensive, but it can’t get wet. Synthetics come in complex profiles, but they require special adhesives. The look you’re after and the specific application (baseboard, casing, crown, or chair rail, for example) will figure in your selection, along with cost, workability, durability, and dimensional stability.

Moldings have a purpose

According to Brent Hull, a historic-moldings expert, interior moldings do two things. First, they define the major shapes and spaces in a room, like doorways, windows, and floor-to-wall and ceiling-to-wall connections.

The second thing moldings do gets at the heart of how to tell good-quality from poor-quality trim. When trim is on a wall, it refines a room architecturally. Profile design, detailing, and scale create the architectural style and tone of the space. But the visual impact is often a subtle, subconscious thing you might not immediately recognize. That visual impact is largely a function of how well defined the profile shapes are and how sharp the profile’s edges are. Hull pushes this point further, adding, “When you look at moldings once they’re installed, you should be able to easily read the shapes that make up the profile.”

Veteran trim carpenter and FHB contributing editor Gary M. Katz agrees: “Crisp, sharp edges create crisp, sharp shadowlines. The relationship between shadow and light is what defines an attractive molding profile, one that can be seen and enjoyed from up close or from a great distance.”

Sharp edges should form around transitions between the shapes that make up the profile. This is especially important with crown molding because it’s installed overhead and because light doesn’t hit it directly. If the profile is muddied with shapes that aren’t deeply, crisply cut, it will look like fuzzy lines against the ceiling.

It’s important to note, though, that the quality of a molding’s profile isn’t a function of the material it’s made from. You can find sharp or muddy profiles on moldings made of finger-jointed wood, MDF, or synthetics.

Profile definition is the first sign of qualityWhen buying trim, look for clearly defined shapes, deep contours, and sharp edges. Profiles with these characteristics yield correspondingly fine shadow-lines, creating an overall impression of refinement and good craftsmanship. Subtle curves with soft edges create fuzzy shadow-lines, which make profile shapes hard to read once the trim is installed. Crown Soft edges become even softer once installed. Uninterrupted by furniture or fixtures, crown molding can do more to unify a room than any other molding treatment. That’s why sharp edges and deep, well-defined profiles make such a big difference. The subtle transitions between shapes and soft edges found on lower-quality crown contribute little visual impact. Profiles shown: WindsorONE Classical Craftsman (left); generic 35⁄8-in. colonial. Casing Shapes should be clearly defined. Less-expensive casing lacks the depth necessary to create definite shapes. High-end versions are cut distinctly and are thick enough to stand proud of the baseboard. Profiles shown: WindsorONE Colonial Revival (left); generic 31⁄2-in. colonial. Base Thicker stock runs straight. Base moldings milled from thick stock have deeper, more-pronounced details and are rigid enough for straighter runs. Because it bends easily, thin base highlights every subtle wave in the wall. Profiles shown: WindsorONE Greek Revival (left); generic 51⁄4-in. speed base. |

Finger-jointed trim is more stable than solid wood

Finger-jointed trim gets its name from the interlocking joint used to connect short boards together end to end. Typically made from various species of pine, finger-jointed trim is free of knots and other defects often associated with solid wood. It’s also less likely to cup because finger-jointed trim wider than 6 in. is made by edge-laminating narrower sections together.

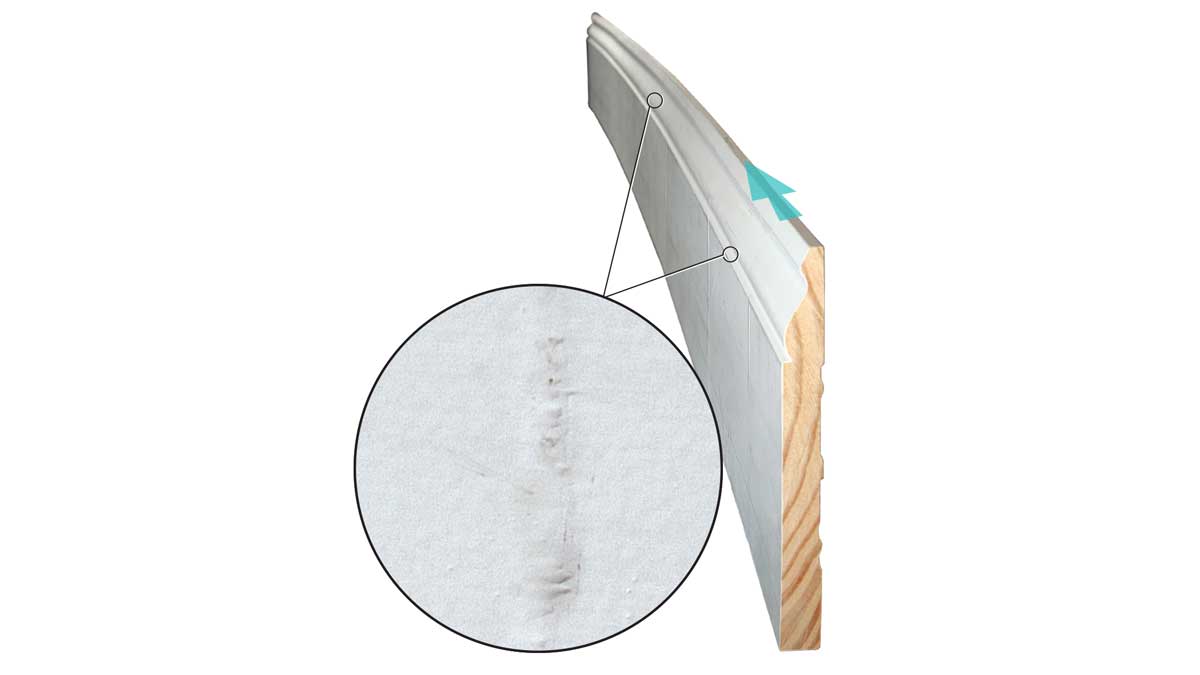

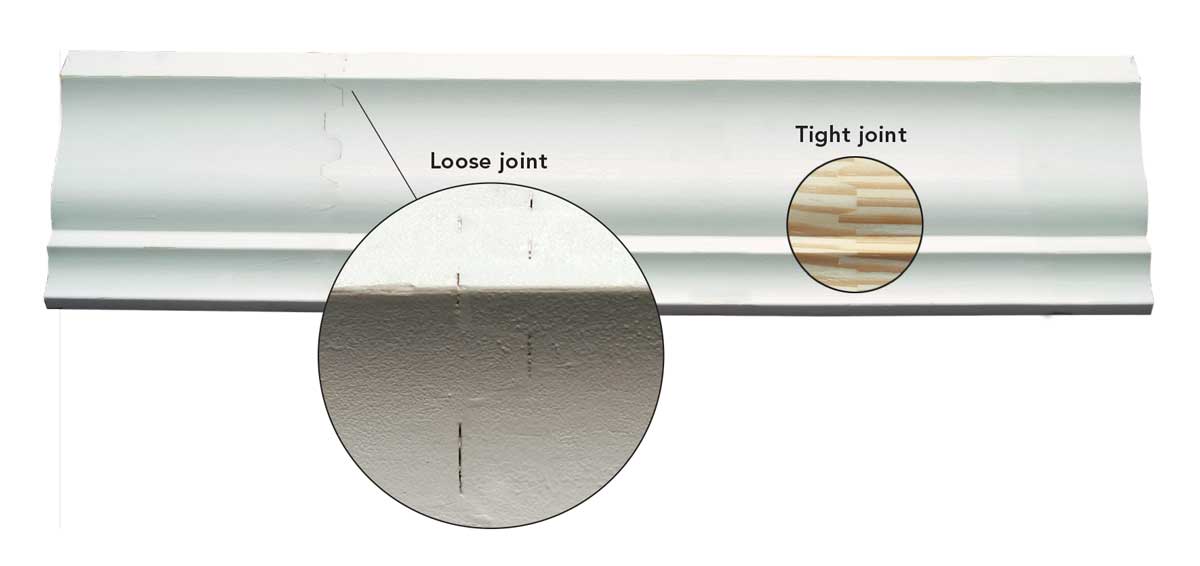

In the past, carpenters complained that finger-jointed trim fell apart at joints or that joints telegraphed through finished surfaces. But according to the manufacturers and expert installers that I talked to, joints fail or telegraph because of poor quality control during the manufacturing process, not because of an inherent weakness in all finger joints.

Kevin Platte, general manager of operations at Windsor Mill in Willits, Calif., said that a strong finger joint depends on two things: tight-fitting fingers and high-quality glue. Although he wouldn’t specify the glue Windsor Mill uses, he did say that they, as well as most manufacturers, use a polyvinyl acetate (PVA) glue. For them, using an ASTM-tested glue that creates a joint stronger than the wood is a must. They and others fortify the glue to make it waterproof.

When a finger joint telegraphs, or shows through the finish, it’s often because wood from different-age or different-species trees is joined. If adjacent blocks in a finger-jointed blank expand and contract at significantly different rates, joint-telegraphing is likely. Trim made with wood of the same species and with trees of the same age is more uniform and stable.

Sharp knives and slower feed rates yield crisp, consistent profiles

One nice thing about finger-jointed trim is that it can be milled with crisply defined profiles. Like solid-wood molding, finger-jointed molding is shaped in powerful machines equipped with molding heads that hold profiled steel knives.

Sharp knives, well-balanced molding heads, and slow feed rates yield the smoothest, most-uniform molding. But maintaining these

optimum manufacturing conditions is more costly, as you might expect. When molding shows up on the job with a rough, chattered surface, it’s usually an indication that feed rates were too fast or that molding heads weren’t properly balanced. Dull knives also can cause rough surface texture as well as profiles that aren’t uniform.

It’s important to be aware of these quality-control issues when you’re buying finger-jointed trim. Trim carpenter and FHB author Gary Striegler always inspects a large trim delivery. “If I see chatter on a board, I return it for a new one,” he says. “To take out even subtle waves in a piece requires sanding. That’s time and labor for me.”

Combining compatible profilesCreating the right tone with moldings requires careful symmetry among base, casing, crown, and other profiles. The wrong combination can be jarring. Most manufacturers offer sets of compatible profiles, but they aren’t always historically accurate or even pleasingly proportioned. Windsor Mill has filled this void by creating well-researched, historically correct collections in popular styles such as Craftsman (photos below), Greek revival, and classic colonial. Their finger-jointed trim takes the guesswork out of finding compatible profiles (www.windsorone.com). |

MDF molding tends to have softer profiles

MDF is made by combining an adhesive resin with wood shavings, chips, sawdust, and other mill waste. The mixture is formed, compressed, and cured in long, flat sheets; then the sheets are ripped and shaped in a molding machine like finger-jointed trim. A Scientific Certification Systems (SCS) rating indicates an environmentally friendly product; this also applies to finger-jointed trim.

According to the folks at Pac Trim, one of the largest MDF trim manufacturers in the country, MDF dulls steel molding knives quickly, so it is always shaped using carbide knives. Carbide knives are considerably more expensive than steel knives, but they keep an edge much longer. Unfortunately, carbide is also more difficult to sharpen than steel and more difficult to shape into sharp-edged profiles. The bottom line is that you’ll be hard-pressed to find MDF products with the kind of sharp edges that are available in high-end finger-jointed and polyurethane options.

Carbide knives that don’t need frequent sharpening and inexpensive material explain why MDF molding tends to be less expensive than finger-jointed or synthetic versions. If high-end finger-jointed trim isn’t within your budget, MDF might be a good alternative. It’s incredibly stable, is available in a wide variety of profiles, and looks surprisingly good.

Although he prefers using solid lumber for trim, Montana carpenter Chris Whalen has no qualms about using MDF. “The long lengths are a little floppy to work with, but it’s inexpensive, easy to cut, and takes paint really well,” Whalen says.

Katz and Striegler said similar things, and both like MDF because of its stability. But Striegler doesn’t like casing doors with MDF because he thinks it’s too susceptible to damage in high-traffic areas. Katz feels differently. “The notion that MDF isn’t all that durable is a myth. I have used it every- where, except in bathrooms,” Katz says. It’s no myth that if MDF gets wet, it swells, bubbles, and falls apart.

MDF molding is smooth and stable

CostTrim prices vary by region, outlet, and quality. Lineal-foot prices below are from Connecticut-based sources. • 51⁄4-in. speed base: 65¢ to $1.60 • 31⁄2-in. colonial casing: $1.05 to $1.90 • 35⁄8-in. colonial crown: 90¢ to $1.90

|

Synthetic trim offers the most-ornate profiles

Unlike finger-jointed and MDF profiles, which are formed by cutting away the material with molding knives, synthetic trim is either extruded or poured into a form. The extrusion process is used for flat trim and simple profiles. Most of these moldings are PVC-based and can be used indoors and outdoors. Most polyurethane molding can be used outdoors, but it’s more commonly used for interior applications. Unlike PVC material, polyurethane trim doesn’t expand and contract significantly in response to temperature changes. This helps to minimize gaps between joints.

Polyurethane is often used for ornate, highly detailed moldings that would be extremely expensive to fabricate in wood. Each length is made in a large rubber or steel mold. Once poured, the liquid expands like polyurethane glue. The more that the liquid expands, the tighter the cell structure and denser the material.

The risk of mismatched profiles is one reason why some people choose higher-quality polyurethane products. To ensure uniform profiles, Century Archiectural Millwork creates molds out of steel rather than rubber. Rubber molds wear out, causing a profile to change. Folks like Century and ORAC Decor guarantee that profiles will match.

Because the raw materials and manufacturing process are more costly, synthetic molding tends to be more expensive than finger-jointed or MDF products. But it’s also not a fair comparison because most synthetic trim is more ornate.

Former trim carpenter turned luxury-home builder Peter Ziamandanis has been using polyurethane moldings for years. He likes poly products because large built-up cornice details are available as one piece, saving labor and often material costs. Ziamandanis says that installing polyurethane moldings is as easy as installing wood or MDF products. “But I always miter inside the corners. You can cope polyurethane much like wood, but it’s difficult to do with highly detailed trim. Because poly moldings are incredibly lightweight, you don’t need to hit a stud to install them. Adhesive caulk and a couple of crisscrossed nails will hold it just fine,” he says.

Because polyurethane-based trim tends to be soft and is damaged easily, many people consider it best used in out-of-reach areas, such as cornices. But some manufacturers (ORAC Decor for one) have high-density products durable enough to be used for casing and baseboard.

Synthetics are lightweight and immune to moisture Unlike finger-jointed and MDF molding, synthetic trim is either extruded or molded. PVC and polystyrene molding is usually extruded to produce flat trim and simple profiles. It can be stamped to add detail, but profiles are usually not as clean and as crisp as what you’d find with polyurethane. Look for products that guarantee that factory-cut ends will match up perfectly at butt joints. For high-traffic areas, look for high-density products recommended for such uses, such as PVC or polystyrene. Some products meet code-required fire-spread ratings, or can be coated so that they do. Major manufacturers include Century Architectural Specialties (www.architecturalspecialties.com), Fypon (www.fypon.com), and Architectural Products by Outwater (www.outwater.com).  CostLineal-foot prices are based on Connecticut and mail-order sources. • Speed base: $3.90 to $4.60 • Colonial casing: $1.40 to $5.50 • Colonial crown: $3.60 to $10 • Built-up crown can cost close to $20  align when butt joints are made as recommended.

|

Thick, even primer coats should be the standard

Manufacturers of finger-jointed and MDF products prime their molding with a similar process. Once the profile has been milled, the newly shaped boards ride a conveyor belt through a box where paint is applied; then they go through a large drying oven.

MDF generally isn’t back-primed, but because it’s such a stable material, it won’t cup or warp, so back-priming is unnecessary. Unlike finger-jointed products, though, MDF is sanded and buffed between coats because cutting profiles raises the fibers, which swell once they’re moistened with paint. You’re unlikely ever to see a raised, rough edge on a piece of MDF trim. But you might find pieces that haven’t been coated evenly.

Molded polyurethane products have a bonded primer coat. The mold is sprayed with the primer before the liquefied poly is added. Because of this process, primer won’t likely chip from the surface. The primer also adds to the durability of the product.

|

Chris Ermides is an associate editor. Photos by Krysta S. Doerfler, except where noted.

From Fine Homebuilding #193