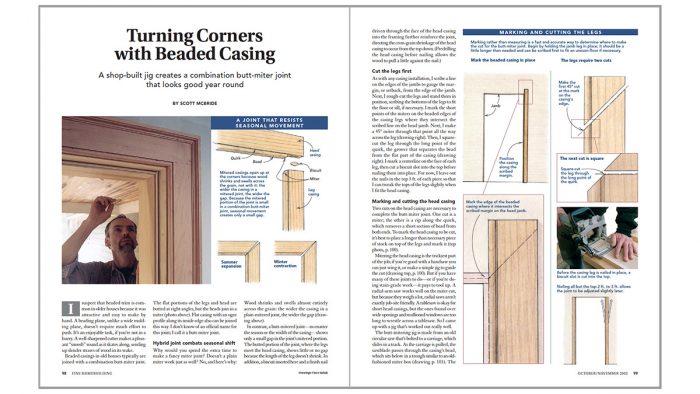

Turning Corners with Beaded Casing

A shop-built jig creates a combination butt-miter joint that looks good year round.

Synopsis: Beaded door and window casings offer an attractive and traditional look, but mitered corners open up with seasonal expansion and contraction. Here the author describes his techniques for cutting combination butt-miter joints that stay snug year-round.

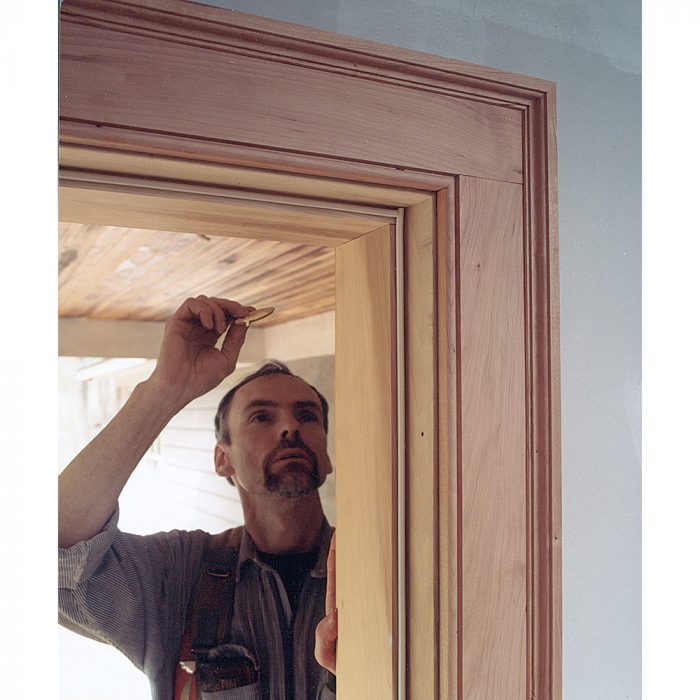

I suspect that beaded trim is common in older houses because it was attractive and easy to make by hand. A beading plane, unlike a wide molding plane, doesn’t require much effort to push. It’s an enjoyable task, if you’re not in a hurry. A well-sharpened cutter makes a pleasant “snoosh” sound as it skates along, sending up slender straws of wood in its wake.

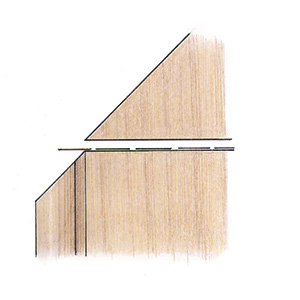

Beaded casings in old houses typically are joined with a combination butt-miter joint. The flat portions of the legs and head are butted at right angles, but the beads join in a miter. Flat casing with an ogee profile along its inside edge also can be joined this way. I don’t know of an official name for this joint; I call it a butt-miter joint.

Hybrid joint combats seasonal shift

Why would you spend the extra time to make a fancy miter joint? Doesn’t a plain miter work just as well? No, and here’s why: Wood shrinks and swells almost entirely across the grain: the wider the casing in a plain-mitered joint, the wider the gap.

In contrast, a butt-mitered joint — no matter the season or the width of the casing — shows only a small gap in the joint’s mitered portion. The butted portion of the joint, where the legs meet the head casing, shows little or no gap because the length of the leg doesn’t shrink. In addition, a biscuit inserted here and a finish nail driven through the face of the head casing into the framing further reinforce the joint, directing the cross-grain shrinkage of the head casing to occur from the top down. (Predrilling the head casing before nailing allows the wood to pull a little against the nail.)

Cut the legs first

As with any casing installation, I scribe a line on the edges of the jambs to gauge the margin, or setback, from the edge of the jamb. Next, I rough-cut the legs and stand them in position, scribing the bottoms of the legs to fit the floor or sill, if necessary. I mark the short points of the miters on the beaded edges of the casing legs where they intersect the scribed line on the head jamb. Next, I make a 45° miter through that point all the way across the leg. Then, I square-cut the leg through the long point of the quirk, the groove that separates the bead from the flat part of the casing. I mark a centerline on the face of each leg, then cut a biscuit slot into the top before nailing them into place. For now, I leave out the nails in the top 3 ft. of each piece so that I can tweak the tops of the legs slightly when I fit the head casing…

To read the entire article, click the View PDF button below.

From Fine Homebuilding #150