Adding Insulation to Basement Walls

Learn how to choose and install the best insulation for several types of basement walls (but fix water-entry problems first).

If you live in South Carolina, Alabama, Oklahoma, Southern California, or anywhere colder, your basement walls should be insulated. In climate zones 3 and higher, basement insulation is required by the 2012 International Residential Code as follows: R-5 in climate zone 3, R-10 in climate zone 4 (except marine zone 4), and R-15 in marine zone 4 and climate zones 5, 6, 7, and 8.

If your home lacks basement-wall insulation, it’s much easier to install interior insulation than exterior insulation. Here’s how to do it correctly.

Make sure your basement is dry

Before installing any interior-wall insulation, verify that your basement doesn’t have a water-entry problem. Diagnosing and fixing water-entry problems in existing basements is too big a topic to be discussed here (but see “Build a Risk-Free Finished Basement” from FHB #248). Suffice it to say that if your basement walls get wet every spring or every time you get a heavy rain, the walls should not be insulated until the water-entry problem is solved.

Closed-cell foam

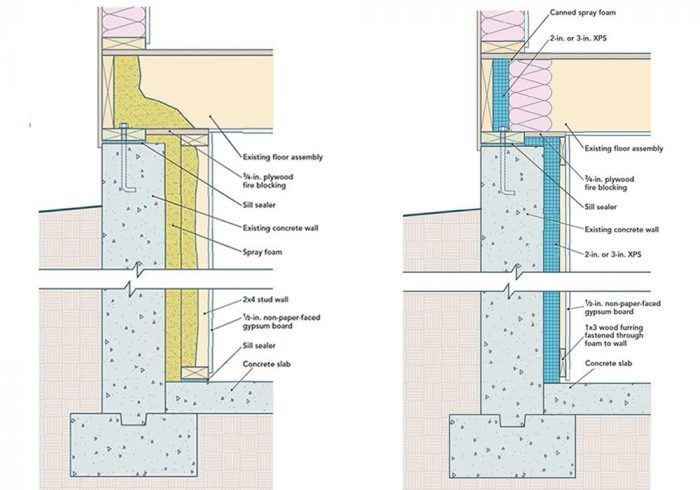

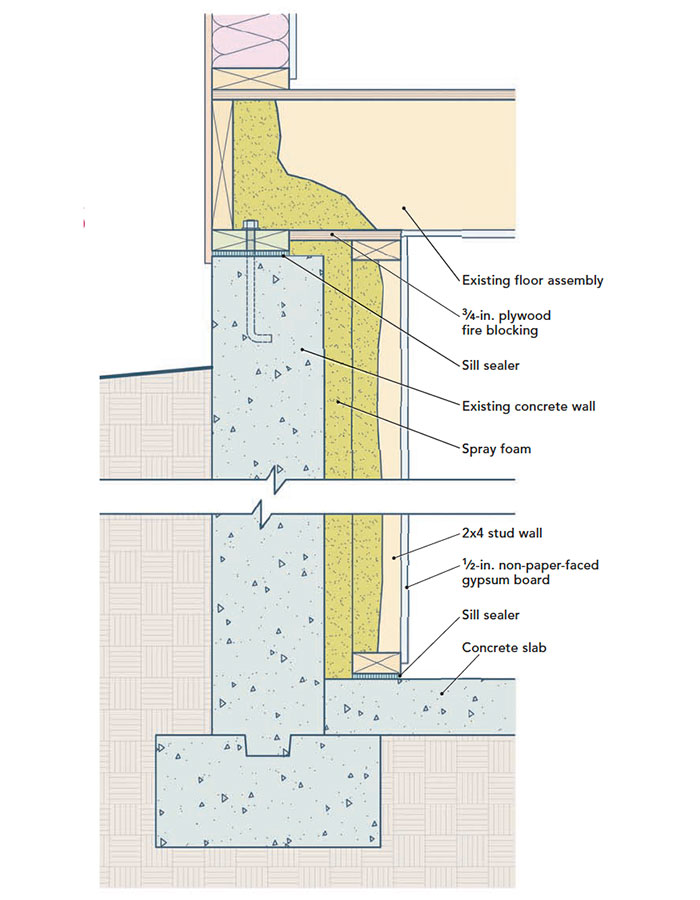

If you want to insulate the interior of your basement wall with spray foam, specify closed-cell spray foam, not open-cell foam. Closed-cell foam does a better job of stopping the diffusion of moisture from the damp concrete to the interior. Frame the 2×4 wall before the spray foam is installed, with a gap of about 2 in. between the 2x4s and the concrete.

Use foam insulation

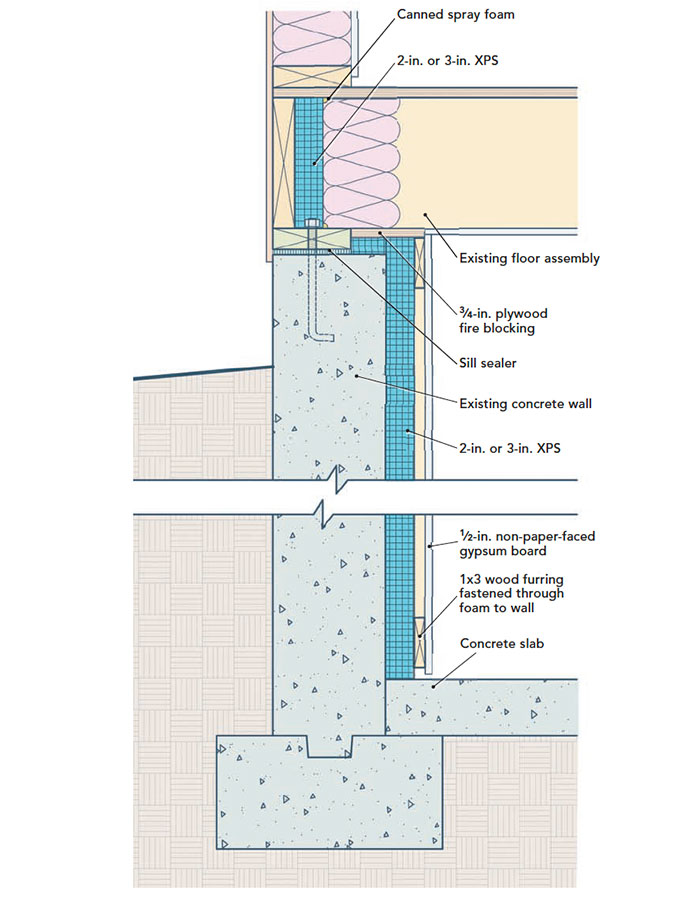

The best way to insulate the interior side of a basement wall is with foam insulation that is adhered to or sprayed directly on the concrete. Any of the following insulation materials are acceptable for this purpose: closed-cell spray polyurethane foam or either XPS, EPS, or polyisocyanurate rigid foam. Rigid foam can be adhered to a poured-concrete or concrete-block wall with foam-compatible adhesive or with special plastic fasteners such as Hilti IDPs or Rodenhouse Plasti-Grip PMFs. To prevent interior air from reaching the cold concrete, seal the perimeter of each piece of rigid foam with adhesive, caulk, high quality flashing tape, or canned spray foam.

Building codes require most types of foam insulation to be protected by a layer of gypsum drywall. Many builders put up a 2×4 wall on the interior side of the foam insulation; the studs provide a convenient wiring chase and make drywall installation simple. (If you frame a 2×4 wall, don’t forget to install fire blocking at the top of the wall.)

If your basement has stone-and-mortar walls, you can’t insulate them with rigid foam. The only type of insulation that makes sense for stone-and-mortar walls is closed-cell spray polyurethane foam.

If you plan to insulate your basement walls with spray foam, the best approach is to frame your 2×4 walls before the foam is sprayed, leaving a gap of 1-1/2 in. to 2 in. between the back of the studs and the concrete wall. The gap will be filled later with spray foam. If you live in an area where termites are a problem, your local building code may require that you leave a 3-in.-high termite-inspection strip of bare concrete near the top of your basement wall.

While reduced costs might tempt you to use fibrous insulation such as fiberglass batts, mineral-wool batts, or cellulose, these materials are air permeable and should never be installed against a below-grade concrete wall. When this type of insulation is installed in contact with concrete, moisture in the interior air can condense against the cold concrete surface, potentially leading to mold and rot.

Don’t worry about inward drying

Some people mistakenly believe that a damp concrete wall should be able to dry toward the interior—in other words, that any insulation on the interior of a basement wall should be vapor permeable. In fact, you don’t want to encourage any moisture to enter your home by this route. Don’t worry about your concrete wall; it can stay damp for a century without suffering any problems or deterioration.

Rigid foam

A 2-in. layer of XPS foam (R-10) is adequate in most of climate zone 4. However, if you live in marine zone 4 or in zones 5, 6, 7, or 8, you need at least 3 in. of XPS or 4 in. of EPS to meet the minimum code requirement of R-15. Furring strips should be fastened to the concrete wall through the rigid foam.

Avoid polyethylene vapor barriers

Basement wall systems should never include polyethylene. You don’t need any poly between the concrete and the foam insulation, nor do you want poly between gypsum drywall and the insulation. If your wall assembly includes studs or furring strips, polyethylene can trap moisture, leading to mold or rot.

Basement insulation is cost-effective

If you live in climate zone 3 or anywhere colder, installing basement-wall insulation will almost always save you money through lower energy bills. It will also provide an important side benefit: Insulated walls are less susceptible to condensation and mold. This means that insulated basements stay drier and smell better than uninsulated basements.

—Martin Holladay is a senior editor.

Drawings: Steve Baczek, Architect.

From Fine Homebuilding #253

RELATED LINKS:

Video Series: Insulate Your Basement – In these 3 videos, learn how to manage water infiltration, air-seal around windows and doors, and add rigid foam insulation to basement walls.

Three Ways to Insulate a Basement Wall – For interior foundation insulation, the safest choices include rigid foam board and spray polyurethane foam.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Great Stuff Foam Cleaner

Disposable Suit

Utility Knife

View Comments

Thanks Martin for another great article with lots of helpful details. One correction and one additional tip re firestopping: (1) 3/4" plywood is not permitted as a firestop at the top of a basement wall as shown in the diagrams; you must use 3/4" OSB or particle board. See IRC R302.11.1 (2) The IRC requires firestopping along a basement wall, at least every 10 feet, to stop fire from spreading horizontally. See IRC R302.11. Typical solutions include (a) fill the space behind a stud with another 2x, pressed against the concrete wall, and (b) fill the space behind a stud with rock wool.

Here is a link to a good article by Contractor Kurt with more details: http://contractorkurt.com/2012/12/31/how-to-firestop-your-basement/

I hope this is helpful.

Mark

Is all vapor barrier bad for basement walls, or just polyethelene?

To: BvilleBound and Martin and Justin Fink,

At the firestop link you supplied, poly is used between the insulation and the studs. Martin, however disagrees in the quote below.

"Basement wall systems should never include polyethylene. You don’t need any poly between the concrete and the foam insulation, nor do you want poly between gypsum drywall and the insulation. If your wall assembly includes studs or furring strips, polyethylene can trap moisture, leading to mold or rot."

Which of these is correct? In a recent article called, "Insulate Your Basement", Justin Fink said, "Also, if you use the appropriate form of insulation the assembly will allow for some inward drying", and, "In theory you can use any type of board insulation, but most people avoid foil-faced polyiso because it doesn't allow any vapor permeability. Vapor permeability in this case is a good thing, because it will allow for some inward drying."

This implies you don't want a vapor barrier, contradicting the use of poly, as well.

Which option do I take? FH and other publications have shown situations where a house is riddled with mold and rot due to bad advice from earlier years. I don't want to go to all the trouble and cost of insulation only to find several years later that I chose the wrong option. How long do I wait until the science is settled?

That is my worry about "building science." A few years ago it was, "ridge vents keep your shingles cooler and they last longer." They are required in many areas. Recently, the revelation was that no, the shingles are still hot. Yes, vapor movement is still true (I hope!) but one of the selling points was false. Was this an hypothesis that was not tested? Why didn't they do rigorous experiments before giving us the advice?

The late physicist Richard Feynman said, "It doesn't matter how beautiful your theory is, it doesn't matter how smart you are. If it doesn't agree with experiment, it's wrong."

Bob