Adding on to a Stone Foundation

Careful excavation, custom concrete forms, and the right concrete mix help to make the job go smoothly.

Question:

My old house has a dry-laid stone foundation that forms a lumpy A-shape in section and is anything but uniform. Inertia keeps the old foundation in place, and gravity and tradition are what keep the house on top of it. I’d like to build an addition on a concrete foundation. What’s the best way to join the two foundations, and how do I create openings in the old foundation to extend ductwork and other utilities from one part to the next?

Steve Culpepper, Woodbury, CT

Rick Arnold, a contributing editor to Fine Homebuilding and a concrete contractor in North Kingstown, Rhode Island, replies: I once knew a guy who poured an addition foundation against a dry-stacked stone foundation. A stone had loosened on the inside of the old foundation, and a whole yard of concrete oozed through before he discovered the problem.

Leaks notwithstanding, joining a concrete foundation to an old stone foundation such as yours can be tricky but not impossible. First, I assume that you want a crawlspace foundation to support your addition. Have your excavator dig 5-ft. to 6-ft. wide trenches up to the two points where the addition foundation will meet the stone foundation. Hire an excavator with a lot of experience: He should have a good understanding of soil conditions, and he’ll know just how far the machine can go before he has to break out the shovel and finish the dig by hand.

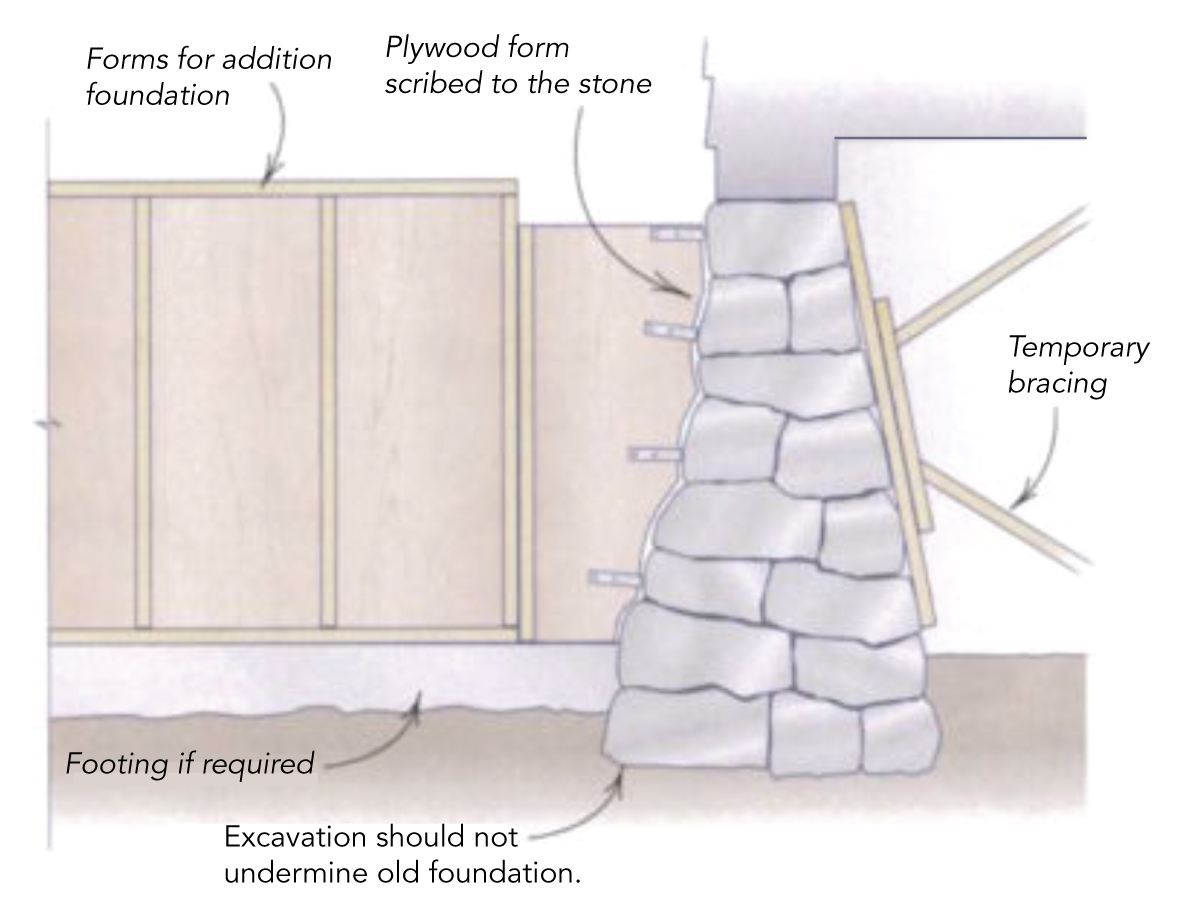

If the depth of the addition foundation is lower than the existing foundation, step back the excavation so that you don’t undermine the old foundation. Be sure to divert down-spouts and all other sources of rainwater runoff safely away from the excavation. Also, coordinate the activities of the foundation contractor and concrete supplier to keep the excavation open as short a time as possible.

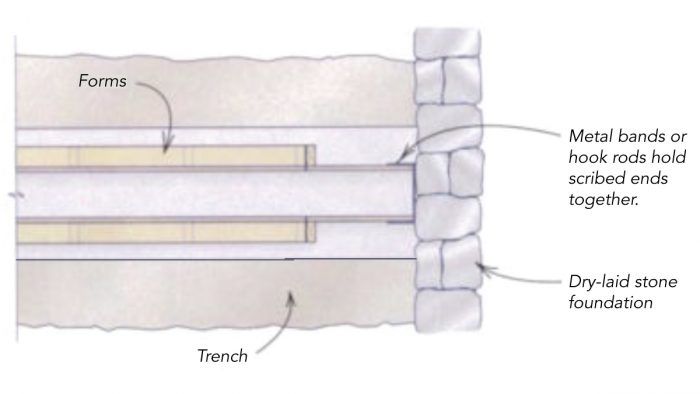

To tie the new foundation to the old, form the new walls so that the concrete flows into and integrates with the irregular profile of the old foundation. When the concrete sets, it will be keyed into the nooks and crannies of the stones. To form the section where the two foundations meet, I make panels of 3/4-in. plywood or oriented strand board. The panels are straight and plumb on one edge where they attach to the nearest form, and I scribe the other edge to match the existing foundation. The scribe doesn’t have to be perfect; 1/2-in. gaps are acceptable.

To join the free ends of the scribed form panels, I usually use jump rods or hook rods. But I’ve also used metal banding along the scribed ends to tie the panels together. Starting at the bottom, I put a rod or a band every foot or so up the panel. By the way, the rebar dowels that tie new work to an old block or a poured foundation are pretty useless in this situation. But I encourage you to brace the stone foundation temporarily from the inside before pouring the concrete.

I usually order the concrete at a 4 or 5 slump, which allows the concrete to flow readily in and around the stone to key the new work to the old. If the concrete starts oozing out, it is probably not stiff enough.

As far as running utilities through the wall, wait until the new foundation has been backfilled and the earth has settled before making holes in the old foundation. It’s better to open a couple of smaller holes spaced as far apart as possible than one large one. Houses old enough to have stone foundations usually have sills made of large timbers, which should span an 18-in. hole easily. Still, I’d avoid making a hole beneath a point load. If the holes need to be bigger or if you’re not sure about the point loads, definitely consult an engineer.

Because of the irregular shape of the stones, it probably will be difficult to remove the exact shape you need for the ductwork and the other utilities. After removing the stone, I build a frame to the right size out of pressure-treated wood. Then I fill in around it with stiff mortar.

Drawings: Dan Thornton