Can You Add Water to Concrete?

It can be tempting to add water to make your mix easier to pour and finish, but be careful or you could weaken the concrete.

Q: Is it OK to add water on-site to a concrete delivery?

—Michael Olander, via email

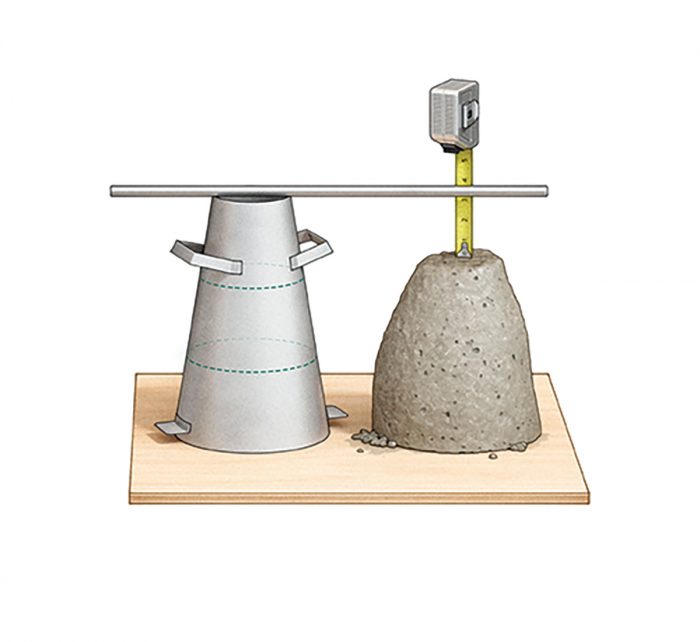

David Crosby, a construction consultant in Santa Fe, N.M, replies: In commercial or institutional construction there will usually be a note in the project documents that prohibits the addition of water at delivery. The design will specify a certain mix of concrete at a certain “slump.” Slump tests are performed as a matter of course in commercial and institutional work, but almost never in residential. During delivery a truncated cone of sheet metal 12 in. tall, 8 in. in diameter at the bottom, and 4 in. at the top is filled with concrete. The form is removed, and how far the concrete sags (or “slumps”) is measured in inches. Concrete that exceeds the specified slump may be refused. It’s typical for concrete for footings or piers to have a design slump of 3 or 4, especially if it will be consolidated by vibration, with a slump of 4 or 5 for flatwork that is not being vibrated.

Residential construction is usually much more casual. It’s generally not a good idea to add water unless the concrete really is too dry and the mix is difficult to work. In that case it might be that a properly added gallon or two of water per yard of concrete may be appropriate for a particular delivery and purpose, but it might not be. Without performing an actual slump test, you’re guessing.

A certain amount of water is necessary to react with the cement and turn the dry ingredients into concrete. This amount is usually not enough to make a plastic mixture; additional water is required to achieve the plastic state that is usually necessary for proper handling, placement, and consolidation. Adding water beyond that will make the concrete flow more easily, but water takes up space in the concrete and changes the water-to-cement ratio, which is a critical factor in the mix design. When the extra water evaporates it leaves empty space, which means increased shrinkage and reduced freeze-thaw resistance, durability, and strength. Too much water weakens the concrete and can also result in slab cracks or curled edges after curing. Foundation walls may develop vertical cracks a few days after the forms come off.

It can be tempting to add water to gain time if the crew is shorthanded, or to make the concrete flow better when working on heavily reinforced structures, or where vibration could be a problem such as with ICFs. If better flow is needed, it’s better to use an admixture such as a superplasticizer. You can get the equivalent of 3 in. or 4 in. of slump with admixtures and be more confident of the consolidation of the concrete. The result will be denser, stronger concrete, sooner.

While it can also be tempting to add water to the surface when finishing flatwork, it’s never a good idea. “Blessing the slab” (working water into the surface with a float or trowel) results in localized weakness at the surface, which will likely cause the concrete to spall, delaminate, or flake, and it will be especially vulnerable to the freeze-thaw cycle. It’s much better to have an adequately sized crew, and if conditions indicate, anticipate the need for more finishing time and order the mix with a set retarder.

From Fine Homebuilding #308

RELATED STORIES