Choosing and Adjusting a Circular Saw

Beyond the choice of sidewinder or worm-drive, there are many other saw and sawblade features to consider.

My earliest recollection of carpentry is of my dad finishing the attic in our rambling Rhode Island ranch house. He used only hand tools and was a sucker for unfinished lauan mahogany paneling. No drywall for him, no sirree. Looking back, I can remember him sweating as he sawed 2×s by hand.

I bought my first circular saw when I was in college to help with building display bases for sculptures. It worked okay. But in 1980, I decided to make my living as a carpenter, and that’s when I bought my first professional-quality circular saw. I still have that saw, and it still works well; it just feels good in my hands. If you’re planning to frame your own home, invest in a good saw—it will pay dividends in accuracy and enjoyment.

Sidewinders versus Worm-Drive Saws

My circular saw is the type known as a sidewinder. The most common version uses a 7¼-in.-dia. blade and is fairly light in weight. But there are other saws. In the late 1980s, I worked on a couple of timber-frame projects. I needed a saw with much more torque to chew through the timbers, so I bought an 8¼-in. worm-drive saw that could cut through red oak at a maximum depth without bogging down. It was years before I realized that carpenters tend to differ in their saw preferences depending on where they live.

West Coast framers use worm-drive saws almost exclusively and consider sidewinders to be toys. The torque of a worm-drive makes it easy to gang-cut stacked lumber, a faster technique than cutting boards one by one. But using a worm-drive all day long is hard work because the tool is just plain heavy. Framers skilled at using a worm-drive saw can use that weight to their advantage when cutting, but veteran wormies will be the ones wearing forearm braces down the road. East Coast framers, on the other hand, prefer sidewinders.

Saw manufacturers seem to change their circular saws like most people change socks. There always seems to be a new gadget or gimmick to make the newest saw a little better than last year’s model. Look beyond the gimmicks when choosing your saw. Read tool reviews in trade magazines and online to see which tools are recommended for longevity, ease of use, and safety. Then go to a tool dealer that carries several different brands. Most professional tool dealers will let you try out a saw at the store.

Be aware of the weight, the size of the handle, and the ease with which you can access the trigger. I know guys with big hands who can’t get their fingers on the trigger of some saws, especially with gloves on. Check to see how easily you can hold the saw while holding the guard in a raised position, a maneuver you must be able to do when cutting steep angles. If you have small hands, difficulty with this feature can be a deal breaker. By the way, you should never remove the guard or clamp it in a permanent retracted position.

After that, look at features such as cord length and amperage. At this point, I would not be tempted to buy a cordless circular saw for constant use because of battery life. A longer cord is helpful, but 6 ft. is usually more than enough. Many companies tout the amperage of the saw motors as a selling point. But if you run the saw off long extension cords, higher amp motors are more likely to trip the job-site circuit.

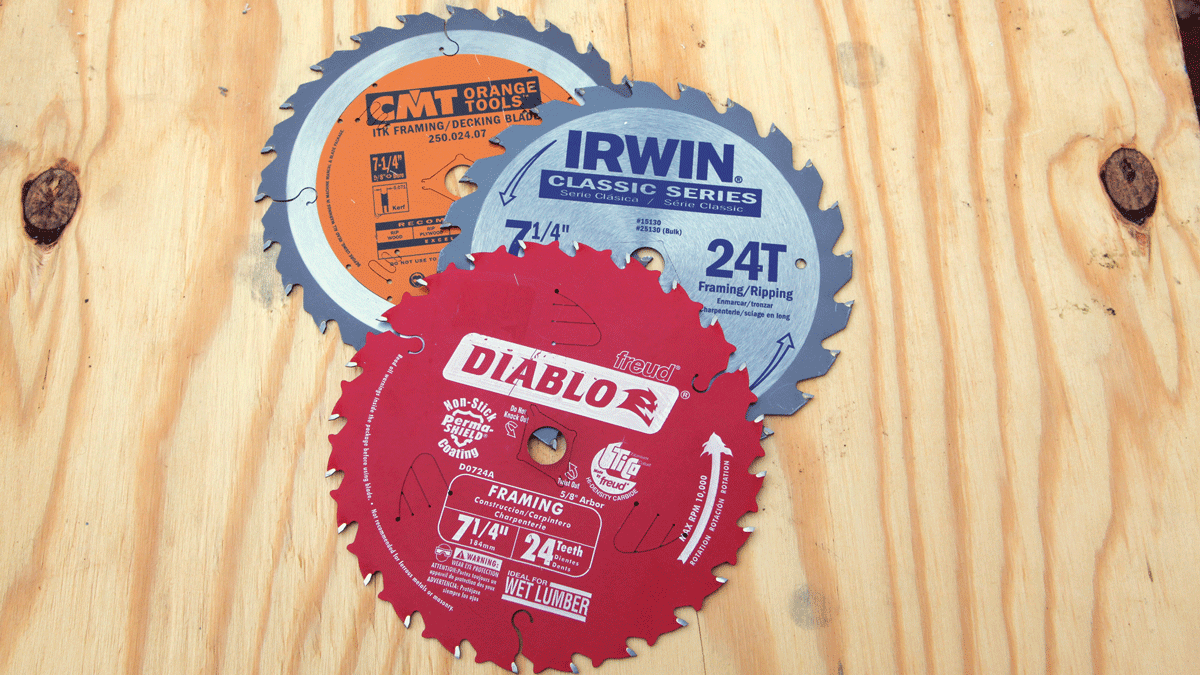

A Good Blade Is a Must

To make any circular saw work at its best, fit it with a good sharp blade. And make sure the blade you get is for framing, not finish work. Most manufacturers label their blades as such. Framing blades typically have 24 teeth set at a positive hook angle for fast, aggressive cutting. You might think that more teeth make a better blade, but when it comes to cutting framing lumber, extra teeth just slow things down.

Most framing blades for circular saws are thin-kerf blades, meaning that the width of the teeth is relatively narrow. A thin-kerf blade removes less wood so it cuts more quickly, an advantage in framing. However, thin-kerf blades may not be the best choice for more precise finish work, where speed is less important than a smooth cut.

Steel sawteeth were once common, but these days hardly anyone bothers with them. The best blades have a carbide tip on each tooth that stays sharp far longer than steel. In the course of framing a moderate-size house, you can expect to run through four to six good blades. Carbide chips if it hits something hard, such as an embedded nail or screw, and even carbide wears down eventually. When you feel yourself having to apply a lot of pressure to keep the saw moving through a board, or if the saw starts to bog down during cuts or consistently pulls to right or left, stop and put in a new blade. If a blade is dull but the carbide teeth are still good, I send it out to be resharpened, but always have a couple of sharp blades on hand to replace it.

Most carbide-tooth blades meet their demise when the carbide on one or more teeth chips or breaks off completely. There are outfits that can recarbide teeth or machine all the teeth down to match a chipped tooth, but those options typically cost more than the blade is worth.

Basic Saw Adjustments

One of the nice features of a circular saw is that relatively few adjustments are needed in the course of a day. But those few adjustments are critical for safety and performance, so practice them a bit before you tackle a project.

Changing a blade The blade in a circular saw is always mounted so the teeth face toward the front underside of the saw’s table. In that configuration, the action of the blade pushes the stock toward the base. Every saw has an arrow (usually on the guard) to indicate the proper direction of the teeth.

When changing the blade, always unplug the saw before you start. Most saws have a shaft lock that keeps the blade from turning as you loosen or tighten the bolt that holds it in place. Engage the shaft lock, then loosen the bolt carefully. Always make sure the saw baseplate is sitting securely on a flat surface and always push the wrench down and away from the n in the opposite direction of the blade rotation, and every saw I know has the blade direction stamped on the housing as a reminder of this.

Squaring the blade to the saw table One last check I always make before starting a cut is to make sure that the blade is perpendicular to the saw’s baseplate. If the blade is tilted even slightly one way or the other, your cuts won’t be square and the joints won’t be tight.

To square the blade, first unplug the saw and then adjust the cutting depth so the blade is at its lowest (most exposed) position. Turn the saw upside down, retract the blade guard, and rest a triangular square against the blade as shown in the top photo on the facing page. If there’s a light background behind the saw, you’ll easily see any gap between the blade and the square. Adjust the angle of the baseplate until the gap disappears. When the blade is set, make a test cut and check to make sure that it’s square. Many saws have a set screw or a stop that lets you return the blade to exactly 90 degrees after you’ve cut at an angle. Once you’ve established that the blade is square, set the stop so that you don’t have to square the blade every time you change cutting angles.

Setting the blade depth Circular saws cut more smoothly and safely when the depth of the blade is set just slightly greater (about ¼ in.) than the thickness of the stock. If too much blade is exposed below the stock, you just might cut through more than you had in mind. But an overexposed blade also increases the chance that the saw will bind and kick back at you (see “Preventing Kickback”). Kickback is a hazard created when the blade of a circular saw twists or gets pinched in the midst of a cut. When kickback occurs, the saw jerks away from the work with such a sudden and violent force that you lose control of the saw before the blade has time to stop. You can imagine the consequences.

To provide an extra measure of protection against kickback, always position yourself beside the saw as you cut; never stand directly behind it.

The easiest way to set the blade depth is to place the saw directly on the stock with the guard pulled up, so that the blade is exposed alongside the stock. Next, release the lever that locks the height adjustment and lower the blade until the proper amount is exposed. Tighten the lever, and you’re almost ready to start cutting.

Preventing Kickback

|

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Protective Eyewear

Speed Square

11" Nail Puller