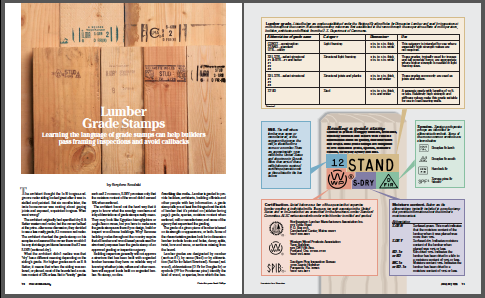

Lumber Grade Stamps

Learning the language of grade stamps can help builders pass framing inspections and avoid callbacks.

Synopsis: A building scientist explains how to decipher the grade stamps carried by every piece of lumber used for structural purposes; with this information, a consumer can determine a board’s specific quality, characteristics, and origin.

The architect thought the 1×10 tongue-and groove cedar siding looked great after it was installed and painted. But six months later, the irate homeowner was ranting about gaping joints and exposed, unpainted tongues. What went wrong?

The architect originally had specified dry B & Better western red cedar, but the owner balked at the price. After some discussion, they decided to use a less costly grade, #2 common red cedar. The architect checked the grade stamp on his samples and assured the owner there wouldn’t be any shrinkage problems because the #2 was S-DRY (surfaced-dry).

What the architect didn’t realize was that “dry” has a different meaning depending on the siding’s grade. For higher grades such as B & Better, it means that when the siding was surfaced, or planed, most of the boards had a moisture content of 12% or less. But in “knotty” grades such as #2 common, S-DRY promises only that the moisture content of the wood didn’t exceed 19% when surfaced.

The architect found out the hard way that it pays to know what the smudgy numbers and inky abbreviations of grade stamps really mean. They may look like Egyptian hieroglyphics or Anglo-Saxon runes, but you have to make sure the grade stamps are there if you design, build or inspect wood-frame buildings. Why? Because building codes throughout the country require that all lumber and wood-based panels used for structural purposes bear the grade stamp of an approved grading or inspection agency.

Building inspectors generally will not approve a structure that has been built with ungraded lumber because they have no reliable way of knowing whether joists, rafters and other members will support loads built on ungraded lumber. No stamp, no dice.

Cracking the code

Lumber is graded to provide builders, architects, building officials and other people with key information. A grade stamp tells you at least five things about the stick of lumber that it’s printed on grade, species, moisture content when surfaced, mill or manufacturer, and name of the agency that supervised the grading.

The grade of a given piece of lumber is based on its strength or appearance, or both. Some of the characteristics graders look for in dimension lumber include knots and holes, decay, splits, twist, bow and wane, or sections missing from the board.

Lumber grades are designated by number (such as #1), by name (Stud) or by abbreviation (Sel Str for Select Structural). Names (redwood), abbreviations (D Fir for Douglas fir) or symbols (PP for Ponderosa pine) identify the kind of wood, or species, from which the lumber was sawn. Some softwoods, such as redwood and western red cedar, are identified and sold individually. Because of similar mechanical properties, others are marketed as species combinations. Purchase SPF (spruce-pine-fir) lumber from Canada, and you’ll get a mix of red, white, black and Englemann spruce; lodgepole and jack pine; and balsam and alpine fir. Even the singular-sounding southern pine is a species combination of loblolly, longleaf, shortleaf and slash pines.

From Fine Homebuilding #103

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Stabila Extendable Plate to Plate Level

Protective Eyewear

Magoog Tall Stair Gauges