Roof-Framing Design

How to handle framing a roof that may be "more complicated than it has to be."

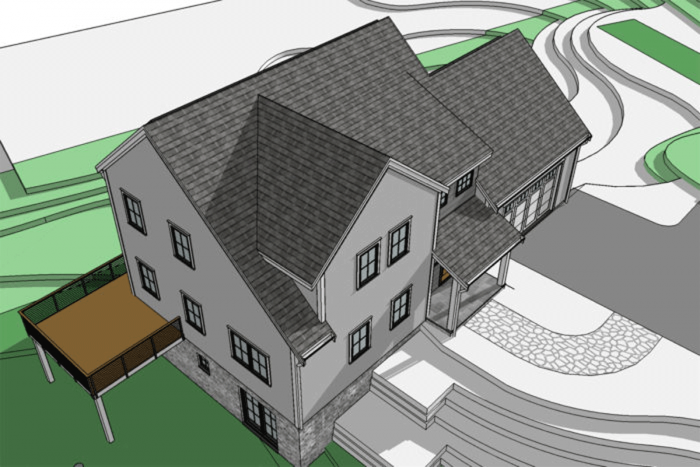

I admit, the roof framing on the FHB House is more complicated than it had to be. Chalk it up to “architectural vanity” if you want. My first design had a very simple gable roof, but it did not provide enough floor space on the second floor. One scheme had only shed dormers, but the design was not appealing enough. The floor plan we chose to go forward with worked with a two-story gable roof, but it would have made for a tall, imposing roofline. Only when we included the north-facing gable cross-dormer on a saltbox form did the design really work. We still needed a bit more floor space for the laundry room and guest/kids’ bath on the second floor, so we tucked in a low-profile shed dormer, recessed to align with the entry wall below. This provided a central volume to balance the garage and the cross gable.

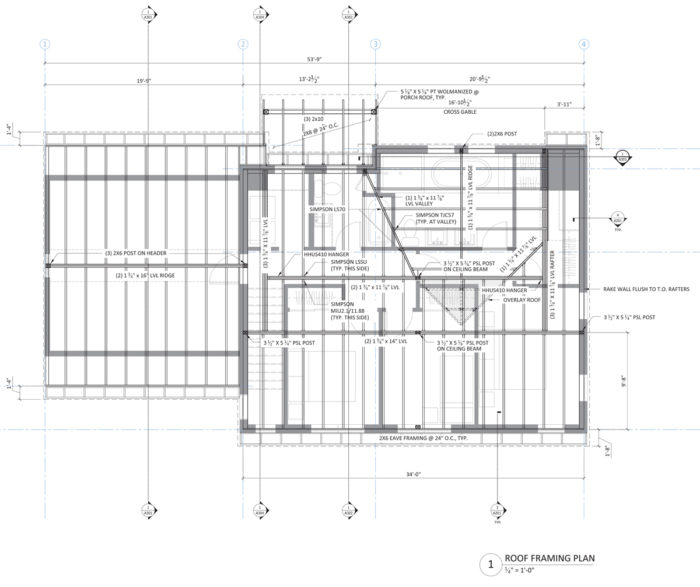

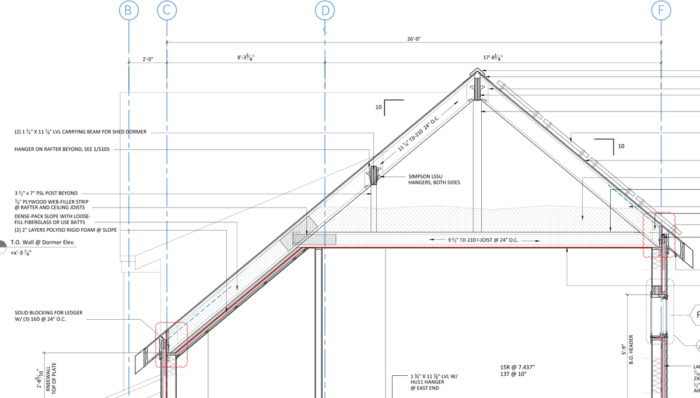

The end result had the design elements we wanted but left the framing design trickier than normal. Fortunately, Mike Guertin is an ace framer, and with some back and forth between us and our structural engineer (Becker Structural Engineers in Portland, Maine), we honed in on the most efficient way to handle the situation.

There are three ways to support a gable roof. You can use trusses, which when it fits the design is my go-to as the most efficient way to get the loads to the ground. Although almost any roof can be trussed, and Mike Guertin and I initially talked about trying to set things up for a truss roof, it just did not work well with the design we settled on.

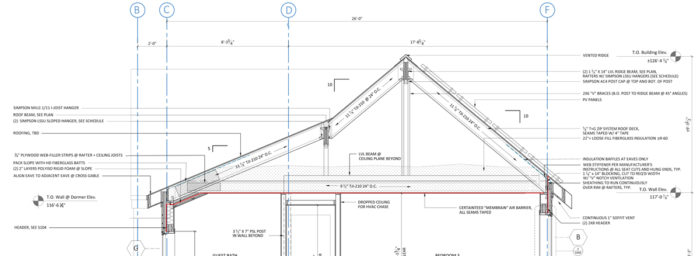

The most traditional approach is to tie the lower portion of the rafters together so they cannot spread. That’s basically what we’re doing at the garage roof, although with the nontraditional detail of setting the rafters above the floor system instead of on the top plate.

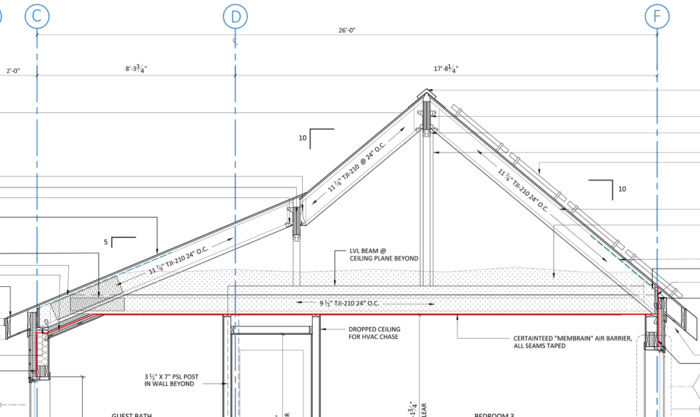

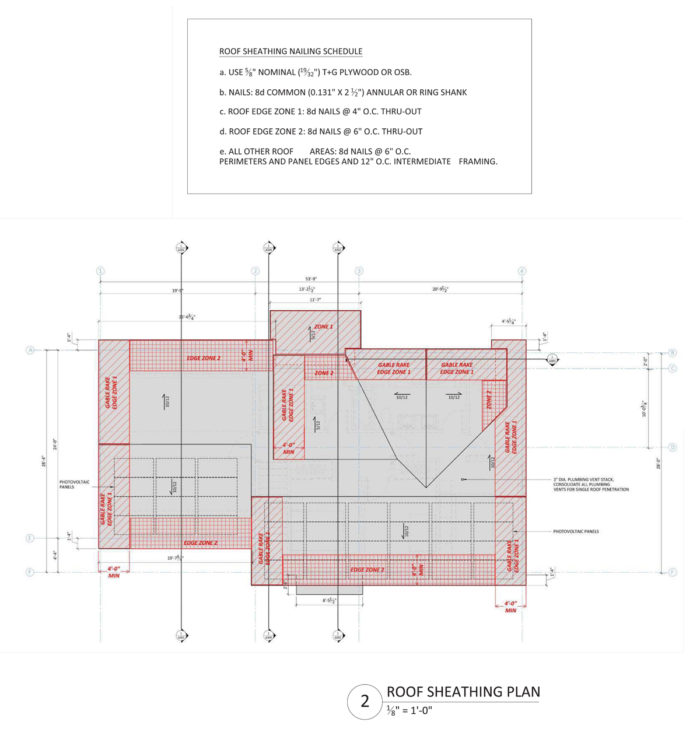

The third option, which I use when roofs start to get complicated, is a structural ridge. The basic concept is that if the ridge can’t drop, the walls can’t spread. The engineering is usually straightforward; you break the loads down into their “projected plan view,” treating them exactly as if the roof were flat, like a floor. Common assumptions such as “Metal roofs or steep slopes don’t hold snow, so the structure can be reduced,” are not accurate. The loads the rafters “feel” do not depend on the roof slope or the length of the rafter; the only thing that matters is the projected plan view. A 6:12 rafter spanning 12 ft. (in plan view) or an 18:12 rafter spanning 12 ft. (in plan view) carries the same structural loads. I should clarify: Wind loads do vary a bit with slope, as do dead loads, but they don’t contribute much to the design load.

There are a few ways that gable dormers are usually tied into the main roof, and a few ways that shed dormers are typically handled. Of course, we had to make things tricky by pushing the two dormers tightly together and then lowering the top of the wall height at the shed dormer so that a portion of the roof slope would be exposed, meaning we couldn’t just land the rafters on a grid of beams. We essentially ran a secondary ridge to pick up the top of the shed dormer.

For simple roofs, manufacturers have prescriptive charts listing beam sizes for various situations. I like to put my structural-engineering training to use and size my own beams when code officials allow, but we had a licensed structural engineer help with the FHB House. One of the trickier aspects when the framing gets complicated is finding the best hanger for each location — one that can carry the necessary load but that is not bigger or more expensive than it needs to be.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

11" Nail Puller

Original Speed Square

Sledge Hammer

View Comments

Thanks, for sharing the information.

Great article, but the drawings are too small to see properly. Why can't I click on them and see an enlargement?