Decoding Framing-Lumber Stamps: Moisture Content, Species, and Grade

Engineers, architects, and builders need to know that the framing lumber they specify and install is strong enough to handle the loads placed on it.

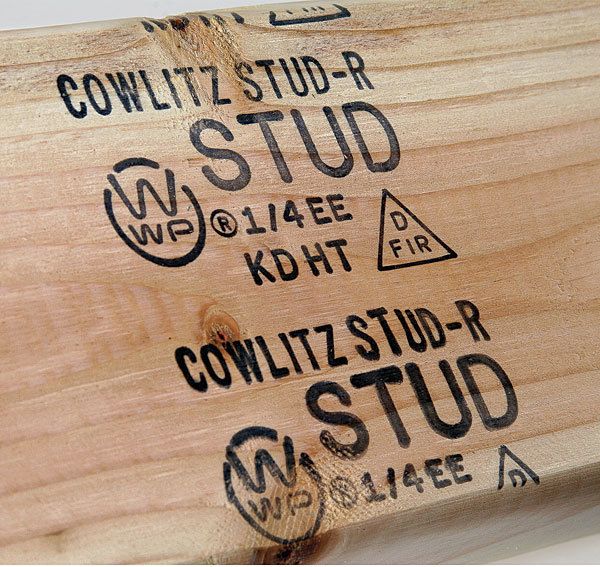

Engineers, architects, and builders need to know that the framing lumber they specify and install is strong enough to handle the loads placed on it. At the same time, they want to build cost-effectively, which involves knowing when a more expensive species or grade of lumber is unnecessary. For these reasons, each piece of framing lumber has a stamp that contains several pieces of information, three of which—moisture content, species, and grade—are essential to know before you start building.

Moisture content

What it says: Moisture content is identified by one of many abbreviations: AD (air-dried to a moisture level at or below 19%); S-DRY (surfaced dry; that is, the board when surfaced at the mill had a moisture level at or below 19%); S-GRN (surfaced green; that is, the moisture level when the board was surfaced was higher than 19%); KD (kiln-dried at or below 19%); and KD-HT (same as KD, although heat-treated as well to kill pests and fungi). KD-15 and MC-15 lumber have moisture levels of 15% or less.

Why it matters: Some builders choose lumber with a higher moisture level for new construction. It’s cheaper, it’s less prone to splitting when nailed, and all the wood will shrink at a similar pace as it dries. Others prefer drier lumber to avoid problems related to shrinkage, such as twisting and nail pops. For remodels, however, go with the drier stuff because it will integrate better with the already dried and shrunken existing lumber. Be aware, however, that moisture content is measured at the mill, not at the lumberyard, so time sitting in rainy weather or hot sun isn’t considered.

Species

What it says: Common wood-species stamps include D Fir (Douglas fir), Hem (hemlock), and PP (Ponderosa pine). Abbreviations are sometimes grouped for species with similar characteristics, such as SPF (spruce, pine, and fir) and Hem-Fir (hemlock and fir).

Why it matters: Species can depend on region, but high-strength lumber often is more expensive. That said, it isn’t always necessary to use the strongest lumber available. Building codes specify maximum allowable spans for each species, so before buying expensive lumber, check local codes to see if a cheaper species could work.

Grade

What it says: There are four categories of framing lumber, most of which have a hierarchy of grades corresponding to their level of weakening characteristics such as knots, splits, or wane.

Structural light framing: These pieces have the highest strength values and are suitable for use in engineered applications such as trusses, rafters, and joists. They are broken down into four subcategories: select structural, No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3.

Light framing: These pieces can be used as plates, cripples, blocking, and in other areas where high strength isn’t crucial. They break down as construction, standard, and utility.

Stud: These pieces are strong enough to handle vertical loads, but they aren’t approved for other uses. No subcategories here.

Structural joists and planks: These larger boards have the same grades as structural light framing.

Why it matters: The farther down the hierarchy you go for each category of lumber, the lower the quality and performance of the wood. Because different species have different strength values, grade must be considered hand-in-hand with species. For example, a 10-ft. Douglas-fir 2×4 of a certain grade will have a different strength value than a Ponderosa-pine 2×4 of the same size and grade. The most important thing to remember here is that within the same species, you can always use a piece of lumber graded above what is required for a particular application, but not one that is graded below.

Photo: Rodney Diaz

From Fine Homebuilding #222