Air-Sealing 101

Learn where to look for common air leaks and how to seal them up to make your home more comfortable and energy efficient.

Synopsis: In this article, Mike Guertin and Rob Sherwood explain how air leaks from houses by way of the stack effect. They show locations in basements and attics where this commonly takes place and then demonstrate how to seal them using silicone, acoustical sealant, and spray foam.

While you might think that air leaks are a problem only with older houses, we’ve tested old homes that are pretty airtight and brand-new homes that leak lots of air. Air leaks occur wherever there is a joint, gap, or hole in the rigid building materials that enclose a house, such as wall sheathing, framing, and drywall.

Making an existing house more airtight is pretty straightforward: Find the holes and seal them up. Many air leaks can be found just by looking for spaces between framing and chimneys, electric boxes and drywall, and the mudsill and foundation. The fixes are often simple and use common materials — rigid foam, caulk, acoustical sealant, and spray foam — which are selected based on the hole size and surrounding materials. The energy savings usually pay for the cost of air-sealing within a few years — almost immediately, in fact, if you do the work yourself.

Air-sealing keeps conditioned air inside the house, but it also improves the performance of insulation such as fiberglass, cellulose, and mineral wool by stopping air from moving through it. In addition, because moisture vapor piggybacks on leaking air, air-sealing reduces the possibility of condensation developing in building cavities, which can lead to mold and decay. It’s also a first step to adding fibrous insulation to an attic in a cold climate. This type of insulation alone does not prevent warm, moist air from escaping the living space. Finally, air-sealing can block gasoline or CO fumes from an attached garage, or moldy air from a crawlspace. Air-sealing does make it more important to vent bathroom exhaust fans and clothes dryers to the outside.

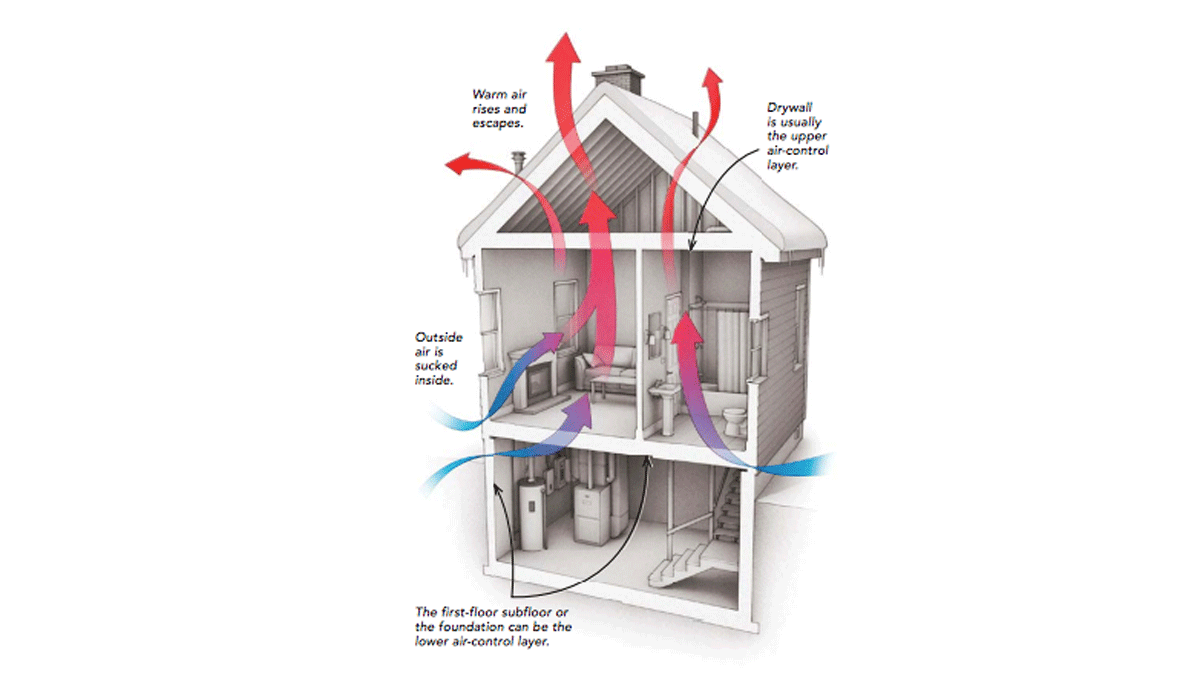

Air moves in and out of houses due to pressure differences between the inside and the outside. The three main forces driving pressure differences are the stack effect, wind, and mechanical fans. Although wind and fans may be important drivers in warmer climates, the stack effect is often the dominant cause of air leaks in heating climates. The stack effect happens when warm air rises and escapes through holes high in the house, much like how a chimney works. Although it’s a weak force, it operates constantly, so it can account for a lot of air movement and energy loss.

Determine your air barrier

Air-sealing starts with deciding which building planes to use as air barriers. A building plane can be the exterior sheathing, sub-floor, or drywall. One way to visualize the air barrier is to look at a section drawing of the house and find a continuous line that encloses the living quarters. The insulation should directly contact the air barrier. Generally that means the air barrier is the drywall or sheathing along the exterior walls, the top-floor ceiling or roofline, and either the foundation wall and slab or the first-floor sheathing. Once you’ve identified the air barrier, look for leaks in it and seal them up, starting with the biggest ones in the attic and the crawlspace or basement.

This article originally appeared in Fine Homebuilding magazine titled “Air-Sealing Basics”.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below:

From Fine Homebuilding #254

View Comments

First, great article which covers all of the essential details for air sealing an existing home! One suggestion: Many people do not know that canned spray foam, e.g. Great Stuff and 3M, is very flammable. The cured foam will ignite at just 240 degrees F, which is significantly lower than the ignition temp for wood studs. Canned spray foam should never be installed near any source of heat, e.g. recessed lights, exhaust ducts, chimneys and fireplaces, heaters, ovens, etc. Both Great Stuff (Dow) and 3M canned foam include versions with "Fireblock" on the label, which leads people to think they are fire resistant -- but these versions still ignite at 240 degrees F! 3M's marketing is particularly egregious, claiming that their foam is "fire resistant up to 240 degrees". These products are also banned for fire stopping gaps around wiring and plumbing in commercial buildings -- and informed residential building inspectors will fail a residential inspection. That's why we always use true fire resistant caulk, e.g. 3M CP 25WB Plus.