Are There Any Reasons to Make Homes ‘A Little Bit Leaky’?

Some builders still worry that air-sealing efforts will lead to rot.

Here are a few recent building code trends:

- Airtightness requirements are becoming more stringent.

- An increasing number of jurisdictions are mandating blower door tests.

- An increasing number of jurisdictions are requiring homes to have ventilation systems.

Among builders, there is some resistance to these trends. During a visit to your local lumberyard, you may hear a builder grumbling: “No one wants to live in a plastic bag. The new airtightness requirements make no sense—these tight buildings are all going to rot. It’s always better to build your walls and ceilings to be a little bit leaky. You need some air movement to keep a wall dry. That’s why walls stayed dry in the old days. Back then, when walls were leaky, we didn’t have as many problems with mold and rot as we do now.”

While these opinions sound like common sense, they are ill-founded. Let’s delve a little deeper into these issues to understand why.

Why, exactly, do you like air leaks?

Builders who argue in favor of leaky walls aren’t always clear about their motivations. To address their concerns, we need to distinguish clearly between two entirely separate issues:

- Issue 1 is a concern about occupant health.

- Issue 2 is a concern about material durability—specifically, a concern about moisture accumulation leading to rot.

Both concerns are legitimate. In this article, I’ll explain why random air leaks aren’t a good way to address either concern.

Ensuring high indoor air quality

We can all agree that “no one wants to live in a plastic bag.” We want our indoor air to be high-quality air.

Most people agree that we don’t want indoor air to be stale or smelly. Others strive to attain a particular technical goal—for example, they may want to keep indoor levels of carbon dioxide below some threshold. Still others may be concerned about toxins—perhaps formaldehyde or carbon monoxide.

Almost everyone agrees that “fresh” air is better than “stale” air—even though most of us can’t define “fresh” and “stale.”

Most of us believe that outdoor air is fresher air than indoor air. (There are geographical exceptions—for example, Beijing and New Delhi—to this general rule.) Most of us imagine (correctly) that the freshest air occurs in a natural setting—in a forest, or on a mountaintop, or on a remote Pacific island, far from urban traffic or industrial plants.

If you are lucky enough to spend most of your time outdoors in a natural setting far from urban areas, you get to breathe fresh air. The rest of us can’t assume that the air we breathe—especially indoor air—is fresh. If we care about this issue, we need to do some research.

Here’s a summary of what we know:

- Unless you live in a city with very polluted air, outdoor air is of higher quality than indoor air.

- You don’t want to live in a building that lacks a way for outdoor air to be introduced, and a way for indoor air to leave the building. To stay healthy, occupants need some air exchange between the indoor air and the outdoor air. For reasons of health, the rate of air exchange shouldn’t be too low. For reasons of comfort and energy efficiency, the rate of air exchange shouldn’t be too high.

Leaving random air leaks in walls and ceilings is not a good way to ensure regular air exchange between outdoor air and indoor air. In a leaky house, the air exchange rate will be high in windy weather and very cold weather (because the stack effect, a powerful driver of infiltration and exfiltration, is strongest during cold weather), but the air exchange rate will be low when winds die down or the weather is mild.

On mild, windless days, the air exchange rate in a leaky house might be insufficient for occupant health. And on cold, windy days, the air exchange rate in a leaky house might be too high, leading to comfort complaints (“this house is drafty”) and high energy bills.

Now that building scientists understand air leakage and ventilation requirements, there is no escaping the conclusion that a modern home needs to have a tight envelope and an adequate ventilation system. (Of course, a very active homeowner could ventilate their home without using any electricity by opening and closing windows as necessary. This would require frequent adjustments in response to changes in wind speed, wind direction, and outdoor temperature, and in response to indoor comfort problems. Few homeowners enjoy this approach to ventilation.)

For more information on indoor air quality, see “All About Indoor Air Quality.”

For more information on satisfying ventilation requirements, see these two articles:

Maybe air leaks keep building materials dry?

A second reason why some builders want to encourage air movement through walls and ceilings is the belief that air movement keeps materials dry and rot-free. The idea is, “You need some ventilation air to keep the wood dry.”

The main problem with this theory is that the air moving through envelope cracks may be helping dry the materials out—or it may actually be increasing the moisture content of your materials. The reason? Sometimes the moving air is dry—but sometimes the moving air is humid.

In general, warm air holds more moisture than cooler air. In winter, indoor air can hold a lot of moisture—and when that indoor air escapes through cracks in the building’s envelope, it can deposit moisture on cold surfaces (including wall sheathing and roof sheathing). In summer, outdoor air can hold a lot of moisture—and when that outdoor air enters through cracks in a building envelope, it can deposit moisture on cold surfaces (especially plumbing pipes and HVAC ducts).

In this way, air leaks in a building envelope can contribute to moisture accumulation in building materials. A classic example concerns crawlspaces. During summer months, vented crawlspaces often accumulate moisture—because when outdoor air enters the crawlspace, the moisture in the air condenses on cool surfaces in the crawlspace. The results can include mold and rot.

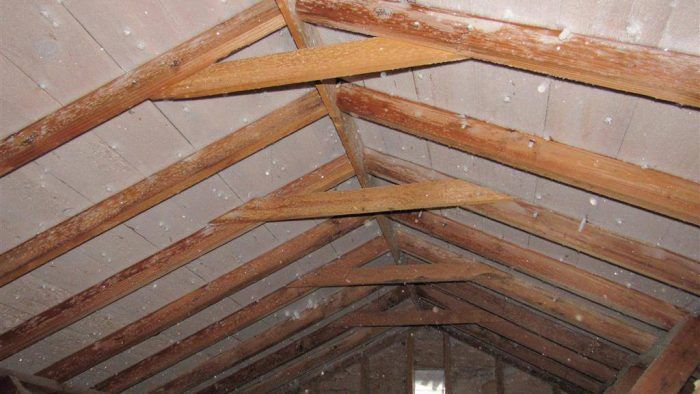

Another classic example concerns moisture accumulation in an attic. When a house has a major hole in the ceiling—especially a hole (like a chimney chase) that communicates with a damp basement—humid indoor air can escape from the house during the winter, leading to moisture accumulation on the underside of the roof sheathing. (See the photo at the top of this page for an example of this phenomenon.)

Solving these two problems involves several measures—but in all cases, it’s a good idea to seal the air leaks.

Needless to say, not all air leaks cause moisture buildup. In many situations, air leaks do help dry out damp materials. But it’s important to remember that air leaks are a double-edged sword—sometimes leading to drying, and sometimes leading to wetting.

The bottom line: If you want to keep building materials dry, focus on air sealing.

What about rainscreens and vented attics?

Some readers are no doubt raising objections to my previous arguments. They’re thinking, “If air movement doesn’t dry out materials dependably, why do we vent attics and rainscreens?”

Good question. The first point to emphasize is that vented rainscreens and vented attics are entirely outside of a home’s thermal envelope. So these types of vented cavities have nothing to do with the supposed advantages of deliberately leaving leaks in a building’s thermal envelope.

A vented rainscreen or a vented attic only works well if there is an excellent air barrier between the vented cavity and the interior of the house. In the case of a vented rainscreen, the system depends on the existence of an airtight layer—usually a layer of rigid foam or sheathing panels with taped seams—between the rainscreen gap and the rest of the wall assembly. In the case of a vented attic, the system depends on the existence of an airtight ceiling. (Without an airtight ceiling, the ridge vents will tend to pull indoor air through ceiling leaks—an undesirable situation.)

On average, air movement through a rainscreen gap tends to dry out the back of the siding and the exterior face of the wall sheathing, for two reasons: (1) the outdoor air is generally at the same temperature, or close to the same temperature, as the surfaces encountered in the rainscreen gap—so there won’t be any cold surfaces that encourage condensation, and (2) the rate of air movement through the rainscreen gap is greatest on sunny days—after all, sun is the main driver of the stack effect in the rainscreen gap—and sunny weather is usually dry weather.

In the case of a vented attic, it should be noted that attic ventilation can be counterproductive. For example, in the Pacific Northwest, attic ventilation can introduce moisture into attics, leading to sheathing mold; and in Florida, attic ventilation can lead to condensation on attic ductwork. So attic ventilation is, at best, a mixed blessing. For more information on these issues, see “All About Attic Venting.”

So why are leaky old homes so dry?

It’s true that old homes often have leaky floors, leaky walls, and leaky ceilings. It’s also true that on average, the air flow through these leaky assemblies tend to keep the materials dry.

However, there are several important additional factors (other than air leaks) that contributed to the generally dry conditions in older houses:

- Older homes often experienced frost buildup on the interior side of wall sheathing or roof sheathing; only fast drying during the spring and summer months saved the sheathing from rot.

- Older homes had uninsulated or poorly insulated walls and ceilings, so heat was continually escaping from these houses during the winter. This escaping heat kept the cavities dry—by baking the lumber. If you wanted to replicate this approach, the method would work—but the energy waste would be enormous.

- Older homes lacked air conditioning—so there were fewer cold surfaces where condensation might accumulate during the summer.

In short, we can’t hold up the leaky homes of the 1930s as models for modern buildings. Today’s homeowners want a home that is comfortable, not drafty; energy-efficient, not energy-wasteful; and adequately air conditioned during the summer. To meet these expectations, today’s contractors need to learn how to “build tight and ventilate right.”

Mistaken ideas often creep back into our brains

Many builders worry about mold and moisture accumulation, and some of them instinctively (but mistakenly) think that air movement (or deliberate air leaks) can help prevent these problems. These ideas often crop up on our Q&A pages; for example, some builders hesitate to tape wall sheathing seams, or worry about sealing the OSB under an insulated floor cavity, out of the mistaken belief that a little air movement will keep things dry.

After the so-called “leaky condo crisis” in British Columbia during the 1990s, this type of mistaken belief even misled a few architects. Several architects began urging builders to drill huge holes in their wall sheathing—four 3-inch diameter holes per stud bay—in hopes that the air leakage and vapor diffusion through the holes would help keep the walls dry. The recommendation was adopted by many builders in British Columbia.

Questions about the technique were posted on GBA in 2012, when a reader from British Columbia shared his plans to leave “gaps in the sheathing” and “drill holes as well to promote drying to the exterior.”

Somewhat undiplomatically, I responded that “drilling holes in perfectly good plywood or OSB is a nutty idea.” I urged that the reader strive for an airtight assembly instead.

Debate ensued. Eventually, building scientist John Straube weighed in; Straube wrote, “I am with Martin: drilling holes in your sheathing is nutty. It might actually help drying because it will tend to increase air leakage, but that is not a good approach.”

Building science is complicated, but there are a few rules that are fairly universal. Here’s one: strive to make your building envelope as airtight as possible. You won’t regret it.

— Martin Holladay is a retired editor who lives in Vermont. This article was originally published on greenbuildingadvisor.com.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Great Stuff Foam Cleaner

Loctite Foamboard Adhesive

Foam Gun