How to Choose Insulation

Five builders and designers from different climate zones share their go-to insulation strategies.

Insulating a new house used to be a no-brainer. It was that step between installing windows and hanging drywall, when the crew spent a few days stapling fiberglass batts between studs and joists. In no time it was out of sight and out of mind.

That was before blower-door tests, performance metrics like LEED and Passive House, and a better understanding of air and moisture movement in buildings. What once was an afterthought is now rife with opportunities to screw up.

The type of insulation, and how it is installed, dictates comfort, energy efficiency, and building durability. And unlike many building materials, this one often is buried in places that are difficult and expensive to revisit. Whoever lives in the house is going to be stuck with the insulation decision for a long time.

The choices aren’t unlimited, but it may seem that way. In addition to ever-popular fiberglass batts, there’s blown-in fiberglass, cellulose, spray polyurethane foam, rigid foam, fiberboard, and mineral wool. Most of those come in more than one variety, and that doesn’t count more exotic options, like denim, wool, mushrooms, and hemp.

Where do you start? That’s the question we posed to five builders and designers who work in a range of climate zones. While their houses are typically designed to exceed code minimums, few construction budgets are unlimited. Spending constraints often have much to do with what kind of insulation is used—especially in a competitive market. Builders often find themselves looking for insulation packages that are affordable as well as effective.

Minimums outlined in the International Residential Code (IRC) are a place to start, but model building codes only describe required R-values of various building assemblies. How builders get there is another question altogether. For R-values and other details on specific types of insulation, have a look at GBA’s Green Basics library.

Keeping it simple in the rainy Northwest

Port Orchard, Washington, is in Climate Zone 4-C, a relatively mild and wet region where keeping bulk water out of the structure is a more pressing concern than sub-zero temperatures. With that in mind, Bryan Uhler, vice president of Pioneer Builders, said the company follows a relatively simply plan in insulating and air sealing what he said are high-performance spec homes.

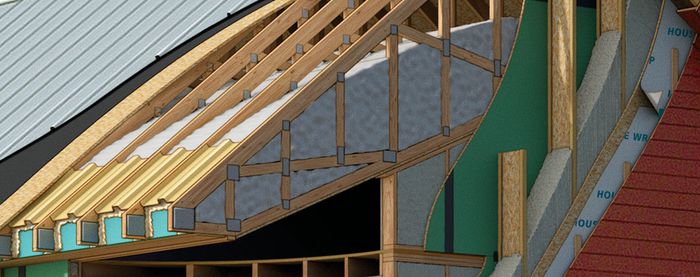

Insulation consists of R-21 fiberglass batts set in 2×6 stud walls framed on 24-inch centers, typically without any continuous exterior insulation. Vented attics are insulated with blown-in fiberglass; cathedral ceilings insulated with R-38 fiberglass batts and ventilated with eave-to-peak air channels. Pioneer has recently started using AeroBarrier—an aerosol sealer dispersed under pressure to plug up gaps in the building envelope—with the aim of hitting 1.5 to 2.5ACH50 with a blower door test. A PVA primer on interior walls serves as the vapor retarder in this wall assembly; drying is to the interior. Houses are equipped with energy-recovery ventilators.

“Because of all of those things, we don’t have to worry as much about our thermal envelope,” Uhler said. “There just isn’t a whole lot of heat transfer going on.”

Although Pioneer has used cellulose in the past, the company’s installer now uses fiberglass, in part because of concerns over what happens should cellulose get wet. The R-21 batts in the wall are enough to beat code by a hair, and while Pioneer has tried using Huber’s insulated ZIP R-Sheathing a couple of times, continuous exterior insulation is typically not part of Pioneer’s approach. One consideration is that the area is in a high-risk seismic zone, so anything that could potentially interfere with the shear strength of a wall is examined carefully. When using Huber’s Zip-R Sheathing, a sandwich of OSB and polyiso foam, the structural sheathing is not attached directly to the wall framing; fasteners go through the foam layer to reach studs.

Uhler does his best to avoid spray polyurethane foam. He thinks that relying on foam as an air barrier is unwise, given the possibility of gaps opening between the foam and the framing. The cost is “astronomical versus what we need in our climate,” Uhler says, and the global warming potential of the foam’s chemistry is another turnoff.

“All of this plays into us keeping our sales price as low as we possibly can at the higher performance point that we can build,” Uhler said.

Working in the humid Southeast

Chandler Design-Build is located in Alamance County, North Carolina, a mixed-humid region on the cusp between Climate Zones 3-A and 4-A. Here, summers are typically hot and humid; winters are relatively mild (an average January day will top out at about 50).

For new construction, Michael Chandler frames walls with 2x6s, 24 inches on center, and fills the cavities with blown-in Johns Manville fiberglass or, if the budget is a little tighter, with R-19 fiberglass batts. Both the top plates and the under side of the roof deck are insulated with open-cell spray polyurethane foam with the goal of hitting R-40. The roof is unvented. Chandler sometimes uses a 1-inch layer of extruded polystyrene foam (XPS) on the outside of the wall. He’s tried the ZIP-R Sheathing, but says he’s had trouble getting his framers do dial back the air pressure on nail guns so that nail heads aren’t driven too deeply.

Foundation walls are insulated with R-10 of expanded polystyrene (EPS) treated with boric acid to repel the ants and termites that thrive in this area.

Like Uhler at the opposite side of the country, Chandler prefers fiberglass over cellulose cavity insulation. When water gets into fiberglass, it simply drains through, he says, where cellulose can hold a boatload of moisture before it becomes evident there’s a leak. Although cellulose itself may not support the growth of mold, wood that’s in direct contact with wet insulation certainly will.

Open-cell foam is vapor permeable, meaning that moisture can work its way through the insulation and potentially condense on the first cold surface it hits. For that reason, it’s usually not recommended for use in roof cavities. Yet Chandler says he’s yet to run into a problem with that assembly, possibly because there’s lot of drying potential during the summer.

Some builders are turned off by XPS because the blowing agents used to manufacture it have a relatively high global warming potential. “It’s not really on my radar,” Chandler said, adding that exterior foam is rarely used because of budget considerations on the smaller, price sensitive projects he often tackles.

“I do care about it, but I think the energy efficiency of the house trumps the propellant in the foam,” he said. “To me, you’ve got to choose your battles.”

When high R-values aren’t enough

Michael Maines is a residential designer in central Maine—solidly Climate Zone 6 where winter weather can stretch from late November to early April. Here, high-performance houses may include double-stud walls or a thick, continuous layer of insulation on the building exterior. Anyone familiar with the “Pretty Good House” concept will recognize Maines’ name and the 60-40-20-10 rule of thumb (R-60 in the roof, R-40 in exterior walls, R-20 for the foundation walls, and R-10 under the slab).

High R-values are important, but by no means the only consideration. To Maines, the chemical composition and embodied carbon of various insulation options looms large in making the most appropriate design choices. Foam, whether spray polyurethane or one of several types of board stock, is increasingly less attractive.

“I’m becoming less and less interested in using high-carbon materials,” he said. “In new construction there’s no reason to use foam above grade. I’ve done some super high performance homes—talking like 0.12 ACH50, five times tighter than Passive House—and no foam. I don’t believe foam is necessary.”

Instead, Maines is likely to specify cellulose in a double-stud wall. The area has plenty of good installers and cellulose has low embodied carbon and performs well thermally. Borate additives protect against mold should the insulation get damp during the winter.

When a double-stud wall isn’t in the cards, Maines might suggest a continuous layer of insulation on the outside of the house. Polyisocyanurate, polystyrene, mineral wool, or wood fiber all are potential choices. Of them, Maines would choose recycled polyiso over any of the other foams, but wood fiber is very attractive to him as well.

“I think it’s awesome,” he said. “It’s a great material. What’s currently available is from super-sustainable forests close to factories.”

Currently, U.S. builders who want to use wood fiber insulation will be ordering Gutex or Steico brands from Europe. However, a spinoff of the Maine architectural firm GO Logic is planning to open the first wood fiber insulation factory in North America in a repurposed paper mill in Madison, Maine, sometime in 2020. “Even the hardcore double-stud people are excited about it,” Maines said.

Even though wood fiber insulation currently must be sourced from Europe, Maines said he’s been told that depending on how and where it’s used, it still can be a net carbon negative material because of the carbon it sequesters. Gaining a U.S. source would make it all the better.

Mineral wool is another option for exterior insulation, but it can be a laborious process to get the insulation to lay flat because it compresses more easily than foam under the strapping for a ventilated rainscreen. And mineral wool also has more embodied carbon than fiberglass. Fiberglass, Maines said, can be a good choice if installed correctly and is used in conjunction with exterior insulation.

“The carbon end of it incredibly important,” he said. “If you’re looking at two materials, one is made from fossil fuels and has a large carbon footprint and is unhealthy to work with and the other one is basically paper and made locally and thermal performance is pretty comparable, then why wouldn’t you go with the low carbon, natural one?”

Building where it’s hot and sunny

The Southwestern U.S. is a complex patchwork of climate zones, so designer Armando Cobo could be working in any one of four of them, from 2 through 5. Cobo, who specializes in net-zero energy designs, believes just about any type of insulation can be used successfully as long as it’s installed properly. That might even include fiberglass batts except for one unfortunate reality.

“You can use batts,” he said, “but one in 10 builders will install it correctly and the other nine don’t. That’s the main reason that I never specify batts, ever. I’ve seen a lot of other builders who use batts, and I will tell you that less than 10% of the installations are what I would consider Class 1. To me, there are a lot of horrible installations.”

Cobo’s go-to package starts with 2×6 framing on 24-inch centers with dense-pack cellulose in the wall cavities. Outside, he uses 1 inch of polyiso rigid insulation. All seams are taped. Open-cell polyurethane foam seals the rim joist. In the attic, Cobo is likely to use blown-in cellulose combined with energy-heel trusses. When he insulates the roof, he may use a few inches of rigid foam above the sheathing or a few inches of spray foam below the sheathing.

Cobo avoids Zip-R sheathing because he thinks the foam is on the wrong side of the assembly.

Occasionally he works with a builder who prefers blown-in fiberglass, but Cobo leans toward cellulose because it’s a recycled material and because it’s capable of taking in and releasing moisture. For rigid foam, Cobo prefers polyiso over XPS or EPS because its chemical components are better for the environment and it has a higher R-value per inch.

But greenhouse gas emissions and embodied carbon are not issues that Cobo weighs heavily in choosing insulation. That’s because he’s been using basically the same materials for more than two decades and has come to trust them. Some of the newer or less familiar materials on the market, such as fluid-applied water-resistive barriers or mineral wool insulation look appealing, but higher costs are a problem.

“The majority of builders in the country, especially in the south, they use the rule of thumb, Number 1, Number 2, and Number 3, and it is price, price, price,” Cobo said.

In New England, using familiar materials

Rhode Island builder Mike Guertin sticks with a straightforward insulation plan. In new construction, that means 2×6 walls on 24-inch centers insulated with cellulose or blown-in fiberglass. Attics get blown in cellulose. Guertin’s use of spray polyurethane foam is minimal.

Because he has access to a blower, Guertin is likely to do his own insulating rather than hire a sub for the job. With many years of practice under his belt, Guertin and his brother can insulate a house in a day or a day and a half, he said, using locally available stock materials and no special equipment.

Guertin is more likely to use damp-spray cellulose than he is blown in fiberglass, even though he has to order in better quality cellulose than is available at his local lumber yard. Cellulose is a little less itchy and rinses off easily when work is over for the day.

If plans call for exterior foam insulation, Guertin steers away from XPS because of environmental concerns and typically uses EPS that is made locally with a borate additive to repel insects.

He is unlikely to use mineral wool on the building’s exterior because it’s more expensive than EPS and installing it is tedious. Mineral wool compresses more easily than rigid foam, meaning the surface may show dips where furring strips have been screwed down too tightly. Guertin’s brother came up with a technique for making sure the surface is coplanar but it involves two 8-foot levels, countersinking screws, and a lot of tinkering.

“So the material costs more and it takes about 50% more time to get the furrings all in plane,” he said. “For the extra performance characteristic of being completely fireproof and having water drain through it, I don’t see the benefit.”

Likewise, Guertin isn’t especially tempted by mineral wool for use as cavity insulation in exterior walls. “I just haven’t seen a case made for it,” he said.

In renovation work, Guertin might use fiberglass batts on a very small job—remodeling a bathroom or kitchen, for instance — simply because it’s more convenient. As much as batt insulation is maligned, Guertin says what he puts in the walls is a big improvement over the 1 or 2 inches of fiberglass originally installed in the 1960s.

A gut renovation of an older house is one of the few times that Guertin would use spray polyurethane foam, and that’s because there’s no great way to air seal an old building with plank sheathing and balloon framing. He’d also make an exception for a cathedral ceiling in a Cape-style house originally built with 2×6 or 2×8 rafters and knee walls in the attic. The best approach there is to gut the whole thing and make an unvented roof with high-density spray foam.

Other than that, Guertin sticks with materials he knows.

“I default to simpler is easier,” he said.

This article originally appeared in Green Building Advisor.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Loctite Foamboard Adhesive

Great Stuff Foam Cleaner

Respirator Mask