Insulating Tight Spaces at the Eaves

There are no easy solutions to this all-too-common problem in older houses.

In most of the U.S. — everywhere but Climate Zone 1 — building codes require the installation of ceiling insulation rated at R-38 or R-49. Achieving these R-values with cellulose or fiberglass requires at least 11 inches of insulation for R-38, or 14 inches for R-49.

These R-value targets are fairly easy to meet for a new house, as long as the designer and builder plan ahead. (For more on new homes, see “Raised-Heel Trusses Make Better Enclosures.”) But owners of older homes — homes built before thick ceiling insulation was code-mandated — often discover that the attic lacks enough room near the eaves to accommodate minimum amounts of insulation. In many cases, the vertical distance between the top plates of the exterior walls and the underside of the roof sheathing is only 6 or 7 inches.

This problem can occur in homes with almost any roof configuration, including those with an attic above a horizontal ceiling as well as those with a cathedral ceiling framed with 2×6 or 2×8 rafters.

“It’s good enough”

It’s common for owners of older homes to post questions on GBA about installing attic insulation. A typical question might read, “When I visited my attic, I found that the attic floor has only 6 inches of insulation. I want to add enough insulation to achieve R-49, but there isn’t enough space between the top plates of the exterior walls and the roof sheathing. What should I do?”

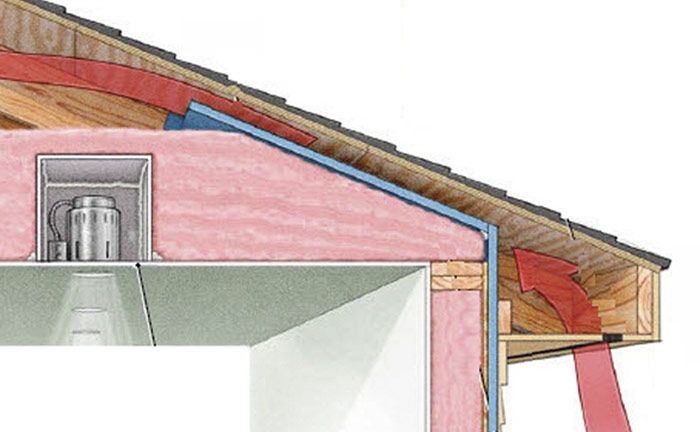

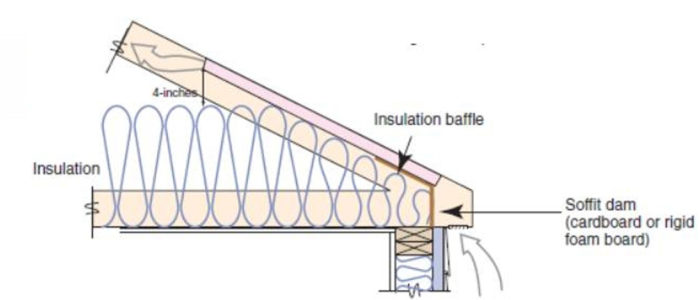

For decades, the typical “solution” to this problem was to install ventilation baffles near the eaves — connecting the air space above the soffit vents with the attic — and then to install as much fluffy insulation (usually fiberglass or cellulose) as there was room for between the top plate of the exterior wall and the ventilation baffle. In other words, call it “good enough” and move on.

The bottom line: You definitely want a full R-38 or R-49 at your eaves. If you have an old house, this is bad news — because achieving that result is expensive.

Rigid foam above the roof sheathing

The answer to the question, “What’s the best way to solve this problem in an older house?”, is simple: The best approach is to install an adequately thick layer of rigid foam above the roof sheathing, followed by a second layer of roof sheathing and new roofing. (For more information on this approach, see “How to Install Rigid Foam On Top of Roof Sheathing.”) Builders adopting this approach can either install all of the needed R-value as rigid foam above the roof sheathing, or they can supplement the rigid foam with additional fluffy insulation installed on the underside of the roof sheathing.

This approach fixes the heat loss problem at the eaves very nicely. It also converts the vented unconditioned attic into an unvented conditioned attic, which has several possible side benefits. (For example, this approach can either provide conditioned space for use as a bedroom or home office, or it can create a good environment for attic air handlers or ducts).

If you decide to go this route, remember to seal all of the soffit vents and ridge vents, and to insulate any gable walls.

The major drawback to this approach, of course, is the high cost of the work. If you end up installing rigid foam above your roof sheathing, you also need to install a second layer of roof sheathing above the rigid foam, followed by new roofing. The cost of this work can add up to tens of thousands of dollars.

Lower the ceiling

In a few rare cases, an older home will have very high ceilings. If your house has 9-foot horizontal ceilings, you may be able to install new ceiling joists to create an 8-foot ceiling, leaving enough room between the two ceilings for plenty of ceiling insulation.

This is an excellent solution, but it’s very unusual to find a house with high enough horizontal ceilings for this approach to be implemented.

If we’re talking about a sloped (cathedral) ceiling, there’s a much greater chance that the “lower the ceiling” approach will work. In many cases, installing a continuous layer of interior rigid foam and new drywall can dramatically improve the thermal performance of a poorly insulated cathedral ceiling — especially if the work is accompanied by air sealing improvements.

Halfway measures

There are several other possible ways to address this problem, but all other approaches are less effective than adding rigid foam above the roof sheathing.

Here is a brief look at other possible approaches:

Install a ventilation baffle and closed-cell spray foam. Closed-cell spray foam provides an excellent air barrier as well as a higher R-value per inch than any commonly available insulation, so this approach is better than just stuffing some fiberglass batts near the eaves. A good installation requires wind-washing dams as well as ventilation baffles. For more information on ventilation baffle options, see “Site-Built Ventilation Baffles for Roofs.”

On the ceiling below the problematic area, install “cornice molding” made of rigid foam. Several GBA readers have made this suggestion over the years, unaware that researchers in 2008 experimented with this approach and found it wanting. To read why this approach doesn’t work, see “Interior insulated cornice for use under low-heel roof trusses?”

The trouble with all of these halfway measures is that the ceiling area near the eaves is still poorly insulated and subject to possible mold accumulation and ice dams. If you are forced by circumstances to adopt one of these halfway measures, the risk of ice dams can be reduced by diligent air-sealing efforts, especially near the eaves.

A hard-to-fix problem

The “tight space at the eaves” problem isn’t easily fixed. In cold climates, tens of thousands of houses with insufficient room at the eaves for adequate insulation suffer horrendous ice-dam problems during snowy winters, and these problems lead to very expensive repair bills.

If you’re planning to buy a home, my advice is to inspect the attic with a strong flashlight. Reject any home with tight space at the eaves, unless you’re ready to accept the very high cost of covering the existing roof sheathing with rigid foam or nailbase.

This article originally appeared on GreenBuildingAdvisor.com.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Foam Gun

Nitrile Work Gloves

Insulation Knife

View Comments

A very thorough article on this topic. Thank you.

An economical option if replacing the roof could be attaching 2x4 "battens" edgewise onto the existing rafters to add an extra 3.5-4.5" of height, where the exact amount depends on the roof's slope. (see sketch)

An even less expensive option is to rip the 2x4s so that they taper from 3.5" to 0" over a span of 8', and then only installing these at the eaves with the taper going up the roof. This would affect the slope near the eaves and cause a "hard" change in slope where the taper ended 8 feet up, but that change in slope would be minor (3.5%), so perhaps other roof install details wouldn't be substantially impacted. On a home with a simple roof design, I'd bet the extra installed cost of the "eaves only" option would be under $4k, and I'd bet the extra installed cost would be around $1k if the sheathing at the eaves was already in need of replacement.

Disclaimer: I'm not sure if there's any compromise of the rafters' structural integrity by attaching these battens. I'd guess not, because we nail sheathing into the rafters every 6" already, but I have not run this by an engineer to get an exact recommendation on attachment details.