The Complicated Role of a Water-Resistive Barrier

Choose the right WRB product and install it well, because if you're not keeping water out, nothing else matters.

Synopsis: Every house needs a dedicated and effective water-resistive barrier to let out wind-driven rain and any other moisture. The role of the material behind the siding has become of the utmost importance. This detailed article describes the purpose of a Water-Resistive Barrier (WRB) and how its performance is calculated, and includes details of the six types of water resistive barriers–standard and drainable housewraps, integrated panels, self-adhering barriers, fluid-applied barriers, and rigid-foam insulation. Also included is data on nine different brands of WRB as well as frequently asked questions about WRBs asked of manufacturers.

As a teenager, I worked for a small general contracting company. In between a lot of grunt work and coffee runs, I learned to do some carpentry. On two jobs, I helped install siding. When we installed cedar shakes, the carpenters taught me to offset each seam as much as possible to keep water from getting behind the siding. When installing clapboards, we backed up all of the butt joints with flashing, which has long been best practice.

Fast forward 20 years: I’m working at Fine Homebuilding, visiting the job site of a high-performance home that was designed by a well-respected architect and is being built by a high-performance builder. On the coast, where wind-driven rain is a regular event, the crew had just finished installing the “open-gap,” or “rainscreen,” siding—that is, siding installed over furring strips with an intentional space left between the boards.

How did we get from laying a healthy bead of caulk where siding meets trim to leaving a wide open space between each course? When did we stop relying on siding to keep water out, and start installing it to let water out? Perhaps it was the mold explosion in homes at the turn of the century and the work of architects, building scientists, and educators like Steve Baczek who showed us that even the best siding installation is no match for water, and that every house needs a dedicated and effective water-resistive barrier, or WRB. “Mother nature has a perfect record,” says Baczek, “Water is the number one killer of buildings.”

The International Code Council agrees. Section R703.1.1 of the International Residential Code (IRC) calls for a water-resistive barrier behind siding and only allows exceptions for some masonry walls and wall assemblies that have been specifically tested to show resistance to wind-driven rain. Regardless of how we got here, the role of the material behind the siding has become of the utmost importance, and manufacturers have responded at warp speed. While you can find code-approved WRBs marketed for every wall assembly imaginable, there’s a lot to know to make an educated decision on how best to keep your walls dry.

Performance data is elusive

According to Yamil Moya, an engineer at the International Code Council Evaluation Service (ICC-ES), the nonprofit that evaluates building materials for the IRC, Type 1 asphalt-saturated felt meeting ASTM standard D226 is the only WRB prescribed in the code. All other products must be approved through criteria created by his organization. ICC-ES acceptance criteria 38, or AC38, is used to evaluate the durability, water resistance, vapor transmission, air leakage, and other qualities of most housewraps. Other product types have different criteria. Fluid-applied water-resistive barriers, for example, must meet ICC-ES AC212.

To meet these standards, manufacturers submit materials including product specs, test results for water resistance and permeability, and installation guidelines. All approved products have a report available online at icc-es.org. Unfortunately, the reports don’t provide test results or evaluate the products, they simple describe the applications for which the products are approved, and give limitations. “Meeting these criteria only means that they comply with minimum requirements,” said Moya, who declined to comment on the quality of individual products they simple describe the applications for which the products are approved, and give limitations. “Meeting these criteria only means that they comply with minimum requirements,” said Moya, who declined to comment on the quality of individual products.

Many experts agree that the tests ICC-ES accepts for water resistance don’t necessarily represent installed conditions. In one test for housewraps, the products are shaped into boats and floated on water to see how long it takes for them to leak. Another exposes the material to a specific column of water for a certain amount of time. According to Peter Yost, a high-performance-building consultant, failure is often the result of water being trapped between the siding and the WRB, a phenomenon called “water held in tension.” Since products are not tested for this real-world situation, Yost says our best option is to install siding in a way that won’t allow it to occur.

More than a product

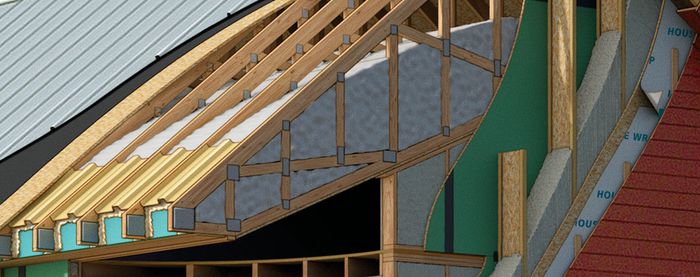

A WRB’s primary duty is to keep water from getting into the walls. The product you choose is part of the equation. But as Baczek likes to say, we can set any product up for success or failure with the way we design the rest of the house. He uses roof overhangs as an example: The greater the length of the overhang, the further away we keep rain and snow melt from the walls.

Baczek, Yost, and most other experts agree that the best thing you can do to give your WRB a chance to succeed is to ventilate your siding. In rainscreen siding installations, the WRB is also sometimes referred to as the drainage plane—the surface that water can run down to eventually escape to the ground. Any type of WRB can be used in this application. However, builders who don’t use furring strips to create an air space may prefer a drainable housewrap—a product with an integral drainage gap.

It is because we hope the water that gets behind the siding will drain that felt, building paper, and housewraps are installed shingle-style with overlapping seams. To effectively keep water out, there’s much more to know about installing a WRB, including how to integrate your chosen product with window and door flashing, how to integrate existing and new products when remodeling, and even how to make repairs when the WRB is accidentally damaged during construction. In other words, even the best products are only as good as the installation.

Air-sealing is possible

The order of the conditions that a wall assembly needs to control is important. Water comes first because everything else is irrelevant if your building starts to rot. Air is second on the list. A tight house is more comfortable and more efficient. And when we control air, we control moisture, because a lot

of water vapor rides on air. A leaky home will have much more water vapor traveling through the walls than a tight home. According to Baczek, vapor diffusion through an airtight assembly is an insignificant problem in comparison to air intrusion in a leaky home. “If I solve for water and I solve for air,” he said, “vapor and thermal are easy.”

For this reason, many architects and builders are turning to WRBs that are also effective and easy-to-detail air barriers. Panel products, self-adhering WRBs, and fluid-applied WRBs can be part of a home’s air-barrier system. While certain products can make water- and air-management a one-step process, be careful as you consider what WRB is right for your project.

Many plastic housewraps are made of airtight materials and are marketed as such, but it’s widely known that they are tricky, although not impossible, to install as effective air barriers. If you plan to go with this type of product, and want your air barrier on the exterior of the wall, a more straightforward option is to tape the sheathing joints and use a combination of tape and polyurethane spray foam to air-seal penetrations.

Walls can still get wet

All WRBs have a listed perm rating that describes how easily water vapor can move through the material. A product with a higher perm rating will allow water vapor to transfer through the material more readily than one with a lower perm rating. Code-approved felt has a perm rating around five when the material is dry, though the perm rating increases to as much as 60 when the felt gets wet. Most WRBs do not absorb water, but that doesn’t mean the perm rating is always consistent. Perm ratings are tested in specific weather conditions, namely under controlled temperature and humidity. When those conditions change around an installed material, so does its permeability.

Carl Fiocchi, a building scientist at the University of Massachusetts, looks for a combination of water resistance, durability, and high vapor-permeability when choosing a product. “For my money,” says Fiocchi, “the higher permeability I can get, the better.” Many experts take this route because even without leaks, walls can still get wet. For example, water vapor from the warm air inside a house can be driven outward during the winter and condense on cold sheathing. In this situation, a more permeable water-resistive barrier won’t trap the water inside the wall.

Michael Aoki-Kramer, managing principal at RDH Building Science, points out that it’s important to know the general thresholds when it comes to perm ratings. “At the upper end, perm rating doesn’t really matter. Above 20, there is no appreciable improvement in drying time. Below 10 perms, you start slowing down the rate of drying in ways that could be appreciable.” While a low perm rating may not be desirable in a wall assembly that you are expecting to dry outward, Aoki-Kramer points out that there are situations where you may want a WRB to resist inward vapor drive. He says that homes with reservoir sidings like brick and stucco that can hold a lot of water may be candidates for a WRB with a lower perm rating.

Finally, the perm rating on a product’s data sheet only tells some of the story. With panel products, the stated perm ratings apply to the water-resistive coatings, not the OSB it’s applied to, and OSB is a pretty effective vapor retarder. How the product achieves permeability matters, too. For example, a plastic housewrap may be perforated or nonperforated. Perforated materials are punched with tiny holes to create permeability while nonperforated materials allow water vapor to diffuse through the material itself. Though both types can pass the necessary testing for code approval, and both may be considered permeable materials, perforated materials have shown to be much less water resistant in independent testing. If you’re building in an extremely wet area, this

may be an important distinction. In a dry area, it may not.

Installation matters

In one simple paragraph, the IRC describes how felt must be installed to meet the requirement for a WRB—horizontally, upper course lapped over the course below by at least 2 in., vertical joints lapped at least 6 in., without “holes or breaks,” and continuous to the top of the wall. That’s it. The IRC says that any other approved product should be “…installed in accordance with the water-resistive barrier manufacturer’s installation instructions.”

The best housewrap manufacturers’ instructions will include not only how much to overlap the horizontal courses and vertical seams, but also a fastening schedule and how to integrate flashings for many different penetrations. According to Mike Guertin, who has been educating the building industry about WRBs for two decades, reverse lapping is still a common mistake, and builders often integrate the flashing incorrectly too. If you mistakenly put step flashing over the WRB where a wall meets a roof, for example, then

any water that gets behind the flashing gets to the sheathing.

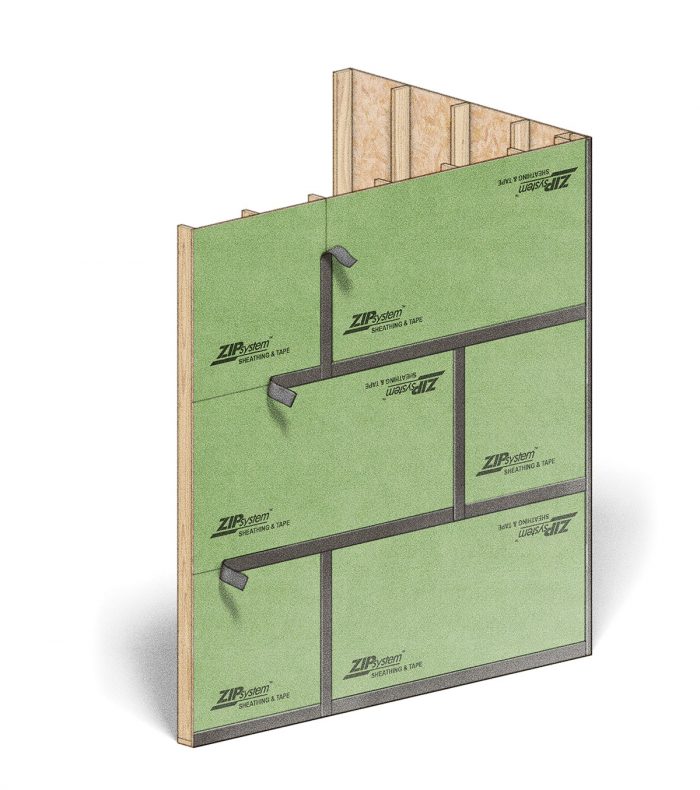

When it comes to using air-sealing and flashing tapes with any type of water-resistive barrier, make sure they are compatible. If this information isn’t listed in the installation instructions, it’s worth a call to customer service to make sure you don’t do anything that will fail or void the WRB’s warranty. While panel-style products will first be installed as structural sheathing, it’s the taping and flashing process that allows them to work as effective water-resistive barriers. The manufacturer’s installation instructions specify which weather conditions are acceptable for taping, how much the tape must overlay each side of the seams, the order of taping seams, and methods for firmly seating the tape—a J-roller may be needed.

Self-adhering WRBs combine installation details for housewraps and panels. Though these products can sometimes be installed vertically, manufacturers encourage shingle-style installations—overlapping courses from the bottom of the wall to the top—and specify how much the courses should overlap. Because these products are essentially big rolls of tape, the right temperature and surface prep are necessary. Like tape, self-adhering water-resistive barriers should be rolled out to improve adhesion.

Though some manufacturers of fluid-applied WRBs require training to use their products, these types are among the simplest to install once you understand the process. On the other hand, using rigid foam as a water-resistive barrier, which can be temping if you are planning to use it for exterior installation, can be very tricky to detail well.

Finally, it’s important to know how long your WRB can be left exposed. While some products offer up to 12 months, more commonly WRBs must be covered within two to four months. One UV-stable product is Benjamin Obdyke’s InvisiWrap UV. Not only is this new water-resistive barrier rated for up to a year of exposure, it’s black with no writing on it and meant to disappear behind open-joint siding. The 25-year warranty allows gaps in the siding of up to 2 in., which prompts the question: How long until we don’t need siding at all?

Six ways to manage water

|

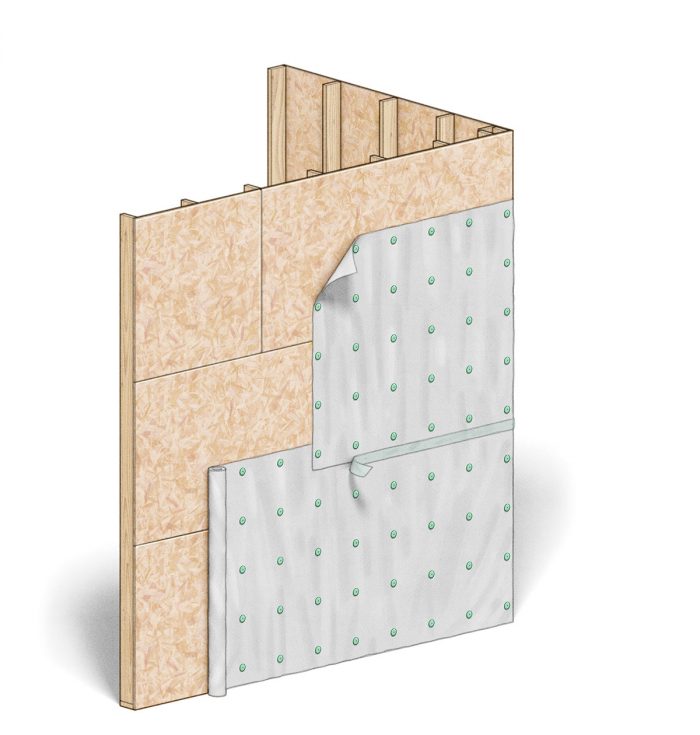

Standard Housewraps Water-resistive barriers that come in rolls and are generally installed with cap fasteners include felt, building paper, and numerous variations of plastic housewrap from DuPont, CertainTeed, Barricade, and many others. Though installation is similar, with courses lapped over each other from the bottom to the top of the wall and flashings integrated for drainage, this category of products varies widely in performance, quality, and price. Even with the seams taped, most of these products tend not to be great air barriers, despite manufacturers’ marketing claims. |

|

|

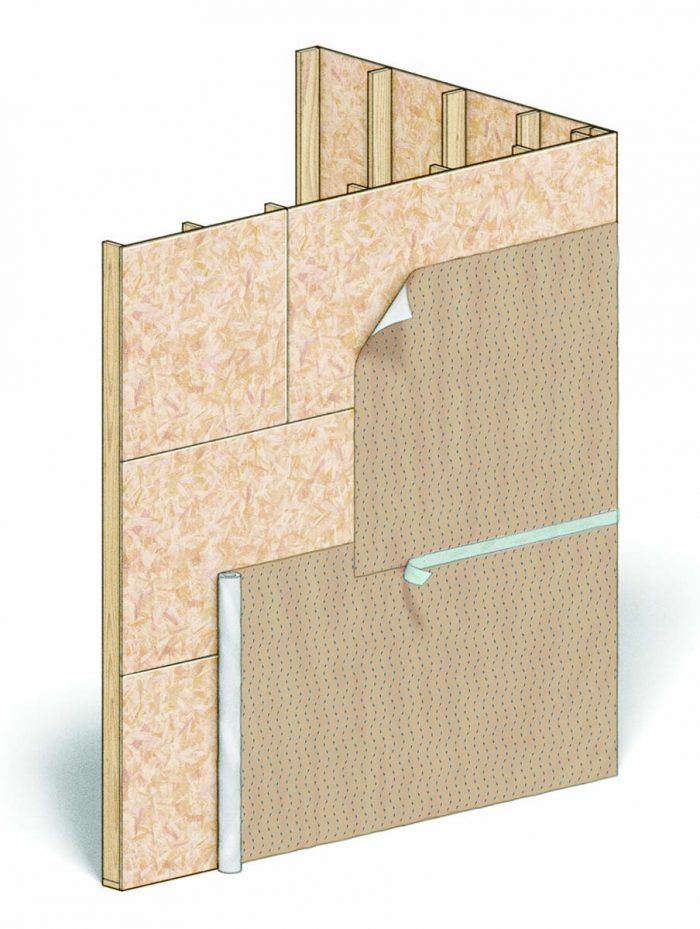

Drainable Housewraps As soon as building scientists spread the word that you don’t need much of a gap behind your siding for water to drain, manufacturers like DuPont, Benjamin Obdyke, Kingspan, and Tamlyn invented a number of ways to integrate a drainage plane with their housewraps. There are products with wrinkles, grooves, dimples, and spacers, all designed to keep siding from trapping water. Most |

|

|

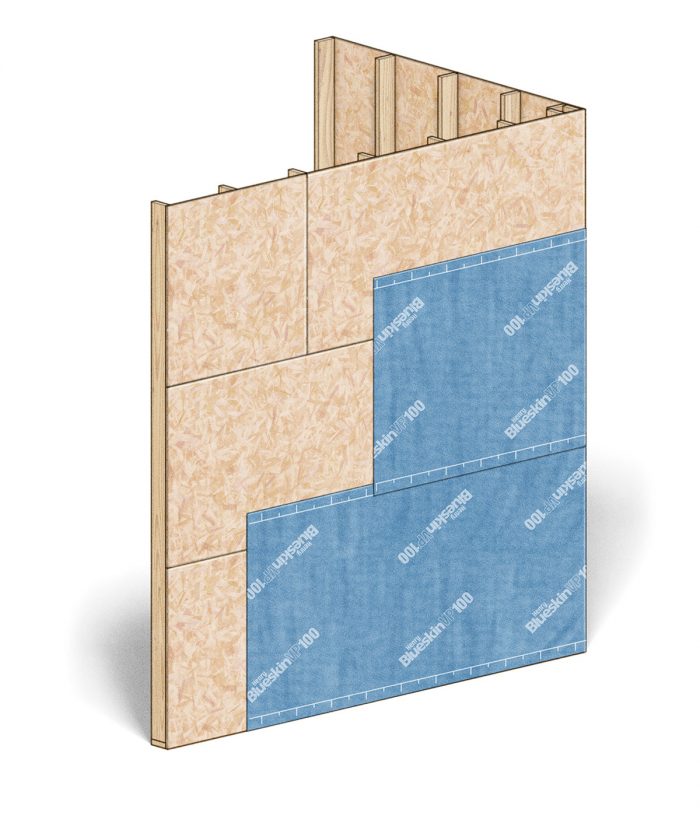

Integrated Panels This style of WRB includes Huber’s ZIP System, Georgia-Pacific’s ForceField, and LP’s WeatherLogic, which are all OSB with adhered water- and air-resistive materials. The benefit is that it takes fewer steps to sheath a house and detail the water and air barriers on the walls. Each company’s panels and tapes work as a proprietary system, but install in a similar way. Critics point to the reliance on the tape—and some people are just not fans of OSB. These systems are slightly more expensive than wrapping standard OSB in |

|

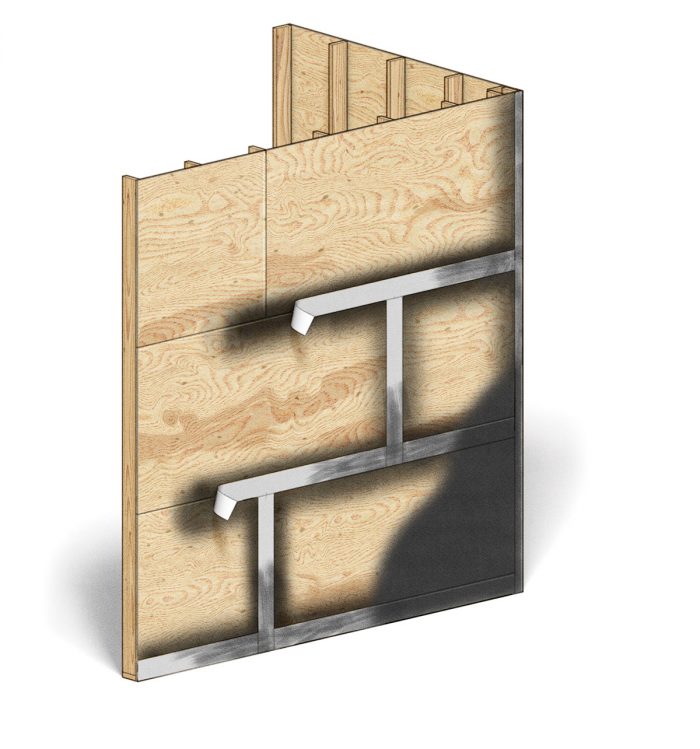

|

Fluid-applied Barriers Sprayed or rolled on to the sheathing, fluid-applied water-resistive barriers have a long history in commercial construction and are slowly being adopted by home builders. Available from companies like StoGuard, Tremco, and Prosoco, they are among the more expensive options, but have some advantages. They efficiently seal the entire sheathed wall from water and air intrusion. Some products incorporate tape at sheathing seams and as flashings at rough openings; others rely on fluid-applied flashing products to complete the system. Some |

|

|

Self-adhering Barriers Peel-and-stick water-resistive barriers from companies like Dörken, Henry, VaproShield, Carlisle, and Pro Clima are growing in popularity thanks to some pretty exceptional benefits. They are rolled out like a housewrap, so the seams lap for drainage, and the adhesive creates a gasket around siding fasteners. Because they fully adhere to the sheathing, they share the air-sealing potential of a panel product. Expect to pay a premium and keep in mind that certain products, substrates, and weather conditions may require that you use a primer before installation. |

|

|

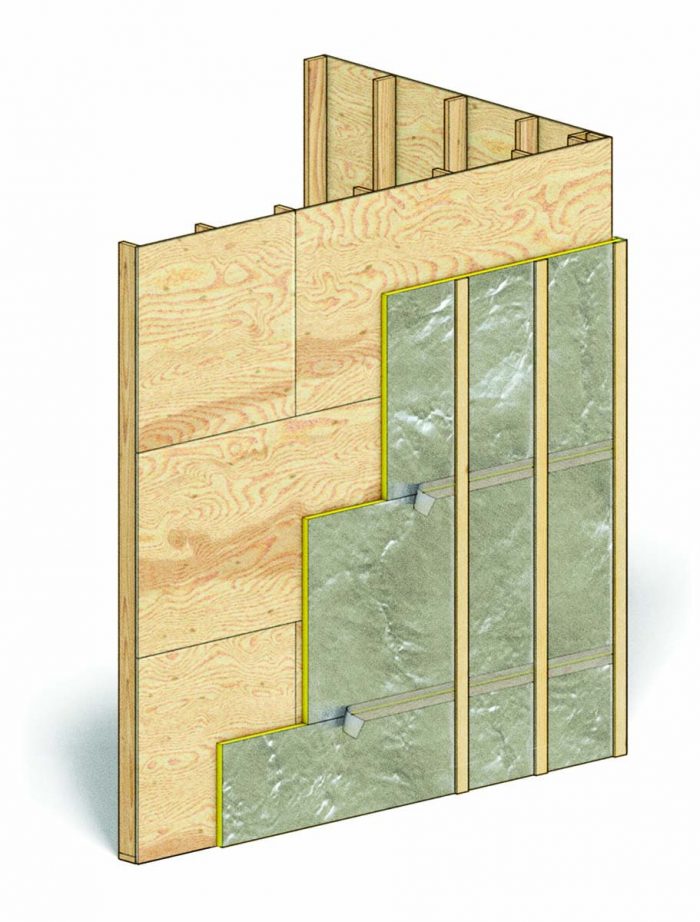

Rigid-foam Insulation There are a number of good reasons to insulate the outside of a house, and this thermal layer can sometimes be used as the water-resistive barrier. But there are some caveats. First, not all foam is approved. If you search on icc-es.org for AC71, the acceptance criteria for rigid-foam panels as a water-resistive barrier, you will find a relatively small number of approved polyiso, XPS, and EPS products. Another important detail is that you need to bring all of your waterproofing out to the face of the foam, which will likely mean furring out windows and doors and could require some tricky |

|

RELATED STORIES:

- Are Drainable Housewraps Enough?

- Making Sense of Housewraps

- Is Your Exterior Rigid Foam Too Thin?

- Self-stick WRB

From Fine Homebuilding #285

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.

Published July 9, 2019.

View Comments

Two pieces of advise:

1. The main benefit of a "rain screen" is to substantially reduce the air pressure that drives water through gaps in the WRB and/or sheathing. The furring strips must be at least 1/8" -- I use 1/4" -- to avoid capillary action. Removable (screwed) perforated stainless steel strips to close the bottom is also a good idea to reduce bugs making a home in the gap.

2. Non adhesive WRD membranes without a rain screen are REALLY a bad idea. "Perfect" installation is necessary to prevent the air pressure pushing water through the and behind the siding and then through and behind even small gaps or tears in the WRB. I would never use these.

Has anyone heard of or had experience with removing self-adhering barriers after they've exhausted their useful life? If you have an antique building with original wall sheathing and you want to use a self-adhering WRB behind new cladding (like cedar shingles), will the WRB come off 50 years later (or anytime later after being placed in service) if the cladding is replaced?