Water-Resistive Barriers

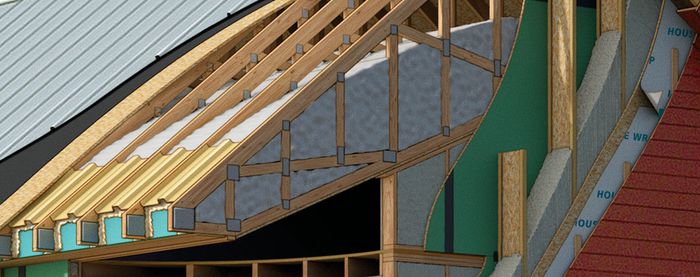

The water-impermeable layer beneath the siding protects walls from rain and snow, and often functions as a building's air barrier.

No matter how carefully it is applied, siding is probably going to leak at some point in its service life. The layer beneath the siding—the water-resistive barrier, or WRB—is what will protect the plywood or oriented strand board (OSB) sheathing from any water that sneaks in.

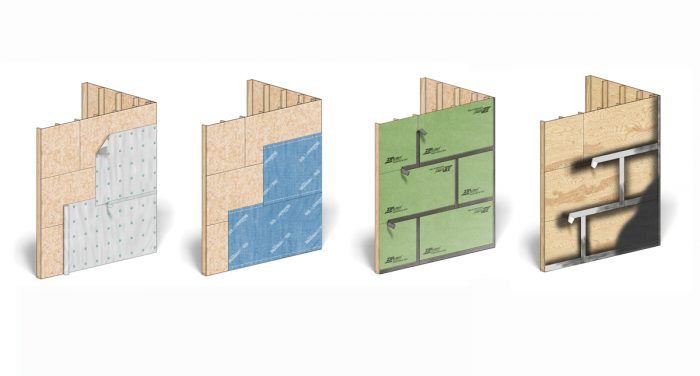

Many builders have turned to Huber’s Zip System sheathing, a type of OSB with a coating of resin-impregnated kraft paper. It’s designed to be water resistant but vapor permeable. With the seams taped, Zip System sheathing requires no further protection before the siding is installed. Those labor and materials savings are a big part of Huber’s marketing pitch, and why so many builders have adopted it.

Builders who haven’t jumped on the Zip System bandwagon have a number of other choices, including asphalt felt, plastic housewrap, rigid-foam insulation, liquid-applied compounds, and Grade D building paper.

Asphalt Felt: An Old Standby

The oldest of the lot is asphalt felt, once an actual felt made from cotton rags but now a much lighter material made from corrugated paper and sawdust. Although the International Residential Code specifically requires asphalt felt (or an approved substitute) over wall sheathing or studs, as GBA editor Martin Holladay writes, manufacturers actually intend it for use on the roof.

Nevertheless, builders can find two modern versions of this old standby at many lumberyards: number 15 felt, which weighs between 7 and 14 lb. per 100 sq. ft., and at least one grade of number 30 felt, which is heavier.

Felt has low permeance when dry, but much higher permeance when it gets wet. That allows it to soak up water and let it dry gradually to the exterior. Some builders consider this to be an advantage.

A similar product widely used in the West, but not seen so much in the East, is Grade D building paper. This is an asphalt-impregnated kraft paper. It’s often used under stucco, but it can be used on any type of siding. It’s less expensive than asphalt felt and because it’s lighter, it’s easier to fold into inside corners. One disadvantage is that it can rot if it gets wet and stays wet.

Plastic Housewrap

Plastic housewrap is typically made from polyolefin fabric and comes in perforated and nonperforated varieties. Two well-known brands are Tyvek and Typar (there also are a number of others). Both are designed to allow the passage of water vapor but not liquid water, the idea being that bulk water won’t get to the sheathing but water vapor will be able to escape.

Housewrap is light, easy to work with, and has good tear resistance. One disadvantage is that they can be damaged by the extractives that leach out of wet cedar and redwood siding (a problem shared to a lesser extent with asphalt felt). Plastic housewrap is not advised for use under stucco because it reacts to the surfactants in cement plaster.

The high vapor permeance of housewrap allows water trapped in a wall cavity to escape. But when the sun is shining on a wet wall, some moisture may be allowed to pass through it toward the interior—what’s called solar-driven moisture.

Wrinkled housewraps are manufactured with small corrugations in the surface, a feature that is designed to turn the material into a drainage plane behind the siding. There’s no universal agreement on how effective these very shallow undulations are in allowing water to drain away. There are many brands to choose from.

Liquid-Applied and Fully Adhered WRBs

Unlike asphalt felt or housewrap, liquid-applied barriers are rolled or sprayed on to form a continuous, seam-free coating that is waterproof but vapor permeable. The process also helps form an effective air barrier.

The process is a little more involved than buying a roll of housewrap at the lumberyard and stapling it in place over the sheathing. New Hampshire–based specialist Andrew Hall, for example, uses a product called Enviro-Dri from Tremco Barrier Solutions that can only be applied by a trained contractor.

Applying this product is a two-step process, beginning with a base coat sprayed on the wall, starting at the bottom and going up. Seams and corners are reinforced with polyester joint fabric before a second coat is applied. The coating is compatible with any type of siding, but it may take up to two days to complete the application on a two-story house of average size. Spray-applied WRBs are among the more expensive options—up to about $1 per sq. ft., compared with the 17 cents per sq. ft. for housewrap.

One advantage of a liquid-applied WRB is that it’s not compromised by fastener penetrations. Fully adhered WRBs, such as Henry Blueskin VP100, offer the same advantage. These peel-and-stick membranes range in cost from 64 cents to $1.08 per sq. ft., and they may require a primer. Installing Blueskin is probably going to be a two-person job (do not let the membrane stick to itself), but it offers excellent air-sealing potential, as Nick Schiffer discovered while renovating a leaky, 150-year-old house.

Rigid Foam

A continuous layer of exterior insulation is an excellent way of minimizing thermal bridging that bleeds heat out of a building through the framing. Can this layer of rigid foam become a WRB? It can, but make sure the foam has been approved for use as a WRB, and pay strict attention to installation details. Also, know that some building experts doubt the foam will be as durable as other WRBs.

Delta-Dry

A more recent addition to the list of WRBs is Delta-Dry, a molded polyethylene product about 1/2 in. thick with an egg-carton-like surface. Unlike other WRBs, Delta-Dry is not vapor permeable—it’s as impermeable as 6-mil poly sheeting. The idea is that because of its profile, Delta-Dry forms air channels on both the front and the back, allowing moisture to escape (top and bottom edges must be vented).

Delta-Dry is especially well suited to wall assemblies that may be damaged by solar-driven moisture. Because it’s vapor impermeable, moisture can’t get through. However, Delta-Dry is sold as a rainscreen product and is to be applied over a separate WRB. Check that detail with your local building office.

RELATED STORIES

- What’s the Building Code for Housewrap Installation?

- What’s the Difference: Control Layers

- Why Use a Spray-Applied Water-Resistive Barrier?

WRBs at a Glance

*Please be advised these prices are subject to change based on the current market.

|

Housewrap (Such as Tyvek)

|

Panels with Integral WRB (Such as ZIP System)

|

|

|

Spray-Applied WRB (Such as EnviroDri)

|

Fully Adhered WRB (Such as Henry Blueskin VP100)

|

|

View Comments

good old saf on the sheathing seams and tyvek. proven for over 40 years and easily fixed. and cheeeeeeeeeeeeap.

lates

Milwaukee - newbie here. What is SAF ? Thanks

I'm gonna guess "self adhesive flashing" for the seams then tyvek.

Some stuff left off in this article, SAF Complex WaterproofingRubberized Asphalt & Felt Sheet Complex Waterproofing System… hint it’s still an oil byproduct?

Regarding some plastic house wraps In a material like spun-bonded polyolefin, the stuff that Tyvek house wrap is made of, liquid water has trouble going through the pores because of the size of the water clusters.which is what happens when there’s a leak in the walls…

I see the editors didn’t talk about “smart vapor barriers”?

This article is woefully inadequate. Please read the installation instructions to understand the complete procedure. Some housewraps are not permeable. Will surfactants damage them? I like liquid applied weather barriers, but the Tremco product doesn't have sufficient solid content. The other liquid wrbs are twice as expensive because they have twice the solids. Check to see if the self adhered products are permeable.

Just spend more time investigating this than relying on this article. FH usually does a better job.