Custom Built-in Cabinets Made Easy

A standardized approach, quick-to-install hardware, and a simplified design make building custom casework cost-effective.

Synopsis: There are some things that factory-made cabinetry cannot provide, and creating a customized solution might be an option that best fits your client’s needs. Coming up with a solid plan and equipping yourself with the right tools and hardware are a few ways that woodworker Tim Snyder creates and installs custom paint-grade built-ins.

Making and installing paint-grade built-ins is a specialty I developed to help clients who can’t get what they need from factory-made cabinetry. My built-in repertoire has come to include bookshelves, cabinets, seats, closet organizers, and desks. Although every project is unique, the goal is always the same: to create a customized solution that makes better use of the space than stock cabinetry. To keep my work somewhat affordable, I developed a process that makes building and installing built-in cabinetry as efficient as possible without sacrificing the look of the finished product.

Part of my efficiency gains have come from learning to maximize my time in the shop and minimize my time in a client’s house, which is always a good thing. I don’t need to offload a bunch of tools and set up a major workspace in someone’s garage. Just as importantly, I can work where noise, sawdust, and occasional profanity won’t cause problems.

Tool up to make the job easier

If you’re set up to do trim carpentry, then you already have most of the tools required for built-in projects. I rely on a track saw for cutting panels to size and for ripping straight, square reference edges on the poplar boards that I use to make face frames. The track saw also comes in handy for fine-tuning the fit of the inset doors I install on many cabinetry projects. To drill pin holes for adjustable shelving, I use a jig made by Milescraft; similar jigs are available from Rockler and Woodcraft.

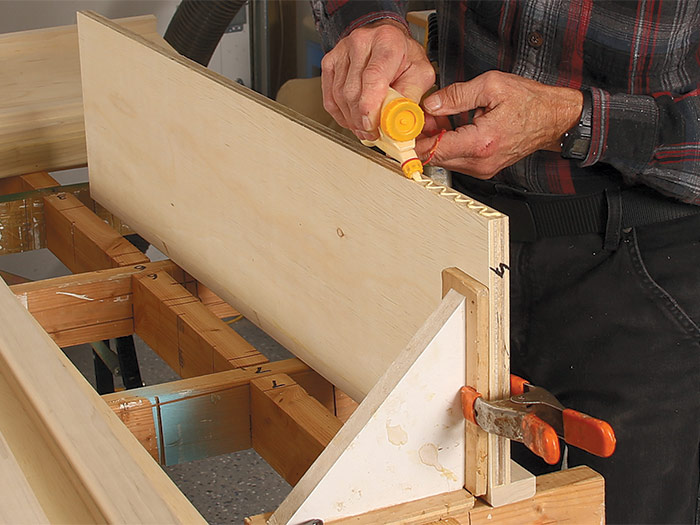

I used to rely on pocket-screw joinery to assemble face frames, and I still use pocket screws on occasion. But today I wouldn’t want to tackle a cabinetry project without my Festool Domino DF 500 mortiser. You could certainly argue that buying an expensive tool to make basic cabinets doesn’t make sense, but hear me out. Festool’s floating tenon joinery system is stronger, faster, and easier than pocket joinery, and it has some very useful flexibility. A variety of tenon sizes enable you to accommodate different stock dimensions. What’s more, by milling a mortise slightly wider than the tenon, you gain a small amount of wiggle room to get joints perfectly aligned during glue-up. Of course, the Domino’s utility extends beyond face frames, into door construction and other woodworking applications. It’s been a game-changing tool in my shop; read more about it on p. 28.

To build paint-grade cabinets, I use hardwood plywood and 3⁄4-in.-thick poplar for face frames and trim. Quality of material varies greatly. That’s why I include a couple of hours for material selection in every estimate.

Start with a site inspection

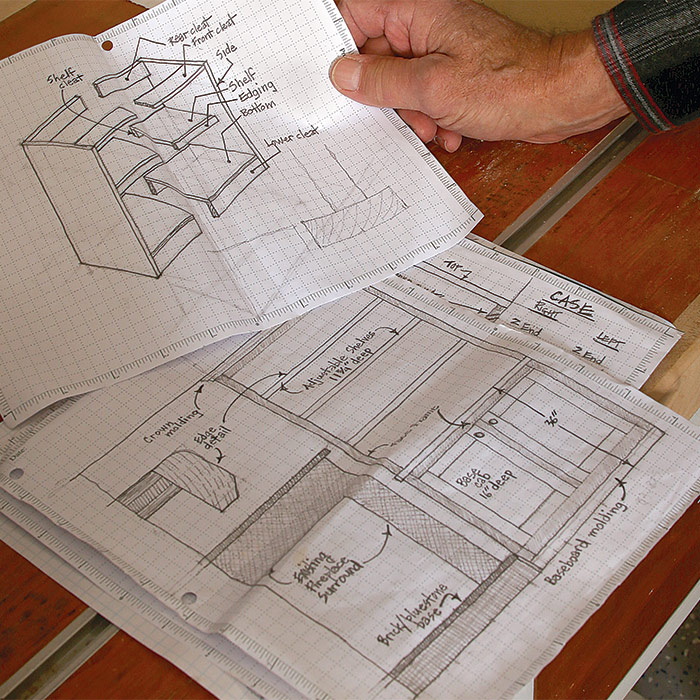

To the site I bring a tape rule, a laser measuring tool, and my phone to take pictures—often with my tape in the photo. I bring graph paper for sketches and notes. It’s critical to not just measure, but to also take stock of the angles and surfaces where the built-ins will be installed. When irregularities in flat, level, square, and plumb are minor (less than 1⁄4 in. over 4 ft.), these details can be recorded on your drawings and accommodated by making allowances for shimming or scribe-fitting during installation.

If I encounter greater variances, I’ll often make a template from 1⁄4-in. plywood. It’s easy to mark a scribe line on a strip of plywood placed against a bowed wall, shape the strip to fit with my block plane, and transfer the scribe to the workpiece back in my shop. Gluing strips of plywood together with hot-melt adhesive enables me to create a template for a corner that’s badly out of square.

Before heading back to the workshop, I use a stud finder to locate the framing for fastening. The site visit also includes a check for HVAC registers, electrical outlets, light switches, and thermostats in the location of the built-ins. In some cases, I’ve been able to relocate a receptacle or extend an HVAC register in the baseboard of a built-in. In others, I’ve had to call in an electrician or HVAC tech to relocate these elements. It’s also important to measure doorways, hallways, and any other choke point that could prevent you from getting the cabinet into the space.

Aim for simplified design

Aim for simplified design

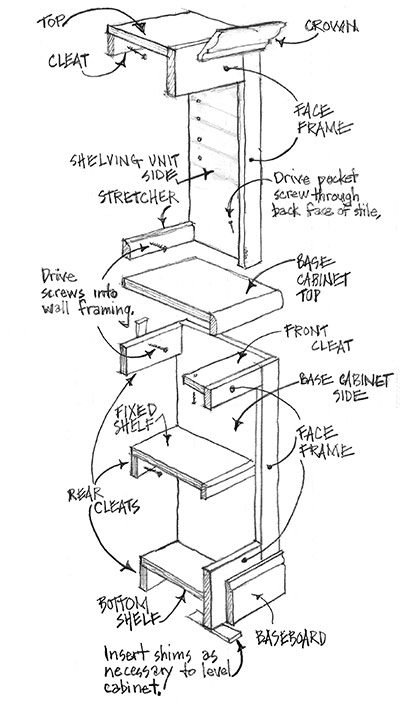

Large-scale built-ins need to be divided into manageable modules to fit into my minivan and through doorways at the client’s house. I take time to make plan, elevation, and detail drawings of every built-in project. The drawings help me optimize material and become part of the estimate I present to the client.

START WITH A SOLID PLAN: If you’re fitting cabinetry into a niche or corner, allow 1⁄8 in. to 3⁄16 in. of clearance between the face frame and existing walls for easy installation and manageable caulk joints. During your site inspection, take note of walls, floors, and ceilings that are uneven, out of level or plumb, or out of square in the installation area. Also identify HVAC registers, thermostats, and electrical switches and outlets that may need relocating.

I always try to simplify the construction details of built-in cabinetry, since this reduces material costs and build time. Back panels aren’t required on cabinets and shelves that will be installed against existing walls. I like ordering cabinet doors rather than building them myself. Suppliers like The Cabinet Door Store offer a variety of door styles, and will size your doors to 1⁄16 in. I sometimes end up building doors myself, if they’re large in size or unusual in design. Otherwise, it’s more cost-effective for me to order out.

Make face frames first — then build boxes to match

Standard practice in cabinet construction is to assemble the casework and then fabricate and attach the face frame. But for many built-in projects, I’ve found that it makes more sense to make the face frame in advance of the casework, especially if the case fits inside a three-sided space as with many bath vanities. In these situations, I make a template to fit the space where the face frame will go, then use the template to make the face frame. If I’m really worried about the fit, I can take the completed face frame to the job site for a final test-fit before building the cabinet boxes.

Construct the shelves

Whenever possible, I have the lumberyard cut plywood case parts to a rough size so the pieces are easier to handle on my own. Back in the workshop, I can use my track saw to cut everything to final size. For identical parts, like shelves, I clamp two layers together and cut both parts at the same time.

|

|

Fit the doors

I order cabinet doors online to the exact size of the face-frame openings where they will be installed. This allows me to trim off just enough material for 1⁄16-in. margins around door edges. After a test fit, I start by cutting 1⁄16 in. off the top of the door. If the opening is slightly out of square, I might need to shave tiny amounts from the two sides as well. I can do this quickly with my track saw, working in increments as small as 1⁄32 in. When trimming the closing edge of the door, I cut at a 3° bevel so the door can close.

No-fuss hardware makes installing doors simple

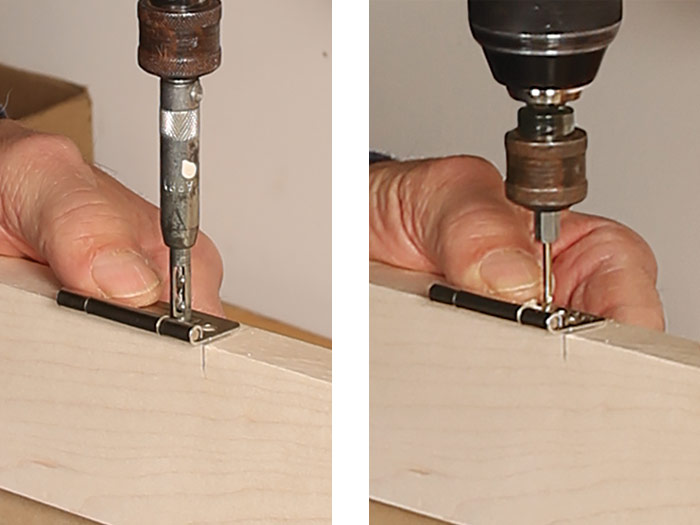

To keep cabinet construction affordable for clients, I save time and frustration with non-mortise hinges for most built-in projects. The Lee Valley hinges are sturdy and reliable and eliminate the time-consuming process of cutting hinge mortises. I primarily use magnet catches to hold doors closed, because they’re easy to install and their pull helps keep doors from warping.

Stack components for a smooth installation

I start with the lowest parts of the built-in, leveling and shimming the boxes and securely fastening them to the wall. I make the top for the base cabinets separately, which allows me to easily scribe the top to adjacent walls for a tight fit. A few finish nails though the top into the cabinet sides holds it in place. Finally, the shelf unit is placed on the base cabinets and fastened in place. On this job, the crown was installed by the general contractor after the stone-veneer fireplace surround (see “Crown on Cabinets,” FHB #309).

|

|

Prep for a perfect paint job

The last bit of work before installation is important. I give sharp corners a couple of strokes with a block plane, then sand all surfaces with 120-grit and then 180-grit paper. Large, flat areas can be sanded with a random-orbit sander; otherwise I work by hand or with a sanding block. A coat of primer makes everything look uniform. I like water-based Kilz 2 all-purpose primer, but I’ve also had good luck with other water-based primers.

On this project we had Magnitude Painting of Bethel, Conn., do an amazing paint job that included caulking the casework to the walls and ceiling. I also want to thank Caetano’s Masonry for the stonework around the firebox, which helps my cabinets pop.

— Tim Snyder; a woodworker in Newtown, Conn. Photos by Patrick McCombe.

From Fine Homebuilding #310

RELATED STORIES

- Maximize Space With Thoughtful Built-ins

- Built-ins for Odd Spaces

- A Smart Way to Paint Cabinets and Built-ins

Originally published September, 2022.